Artist, Activist, Curator

One of the initiators of the exhibition Foreign Students of the HBK in 1973 was the South African student Gavin Jantjes, who, with A South African Colouring Book, created a decidedly political work during his time in Hamburg. Dr. Astrid Mania writing about the former student of the HFBK Hamburg.

Roughly two years ago, my friend and colleague Bea de Souza approached me about a conference on artistic exchanges between African and German-speaking countries she was involved in preparing. Would I be able to contribute with some research on South-African born Gavin Jantjes and his time at HFBK?[1] Jantjes, a renowned artist, activist, lecturer, and curator is, I dare to say, nonetheless not on the first-spring-to-mind-list when it comes to our former students. And this, even though he was involved in organizing one of HFBK’s first exhibitions of international students, participating with what is possibly his most famous work to date, a product of his Hamburg years.

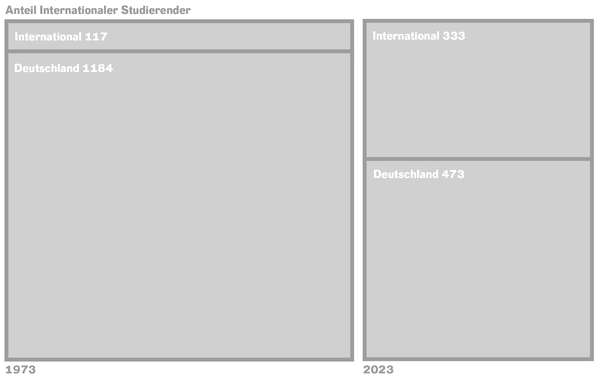

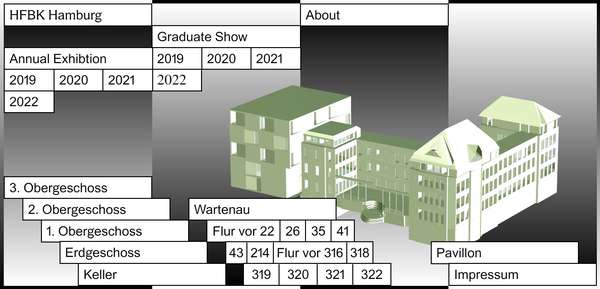

The information is all there. Upon my inquiry, Julia Mummenhoff immediately produced from the archive the 1973 catalogue Ausländische Studenten der HBK (as HFBK was abbreviated back then). It accompanied the exhibition with its 23 international participants who, from June 5–15, had shown their works in the assembly hall. It had been initiated by HFBK’s then director Herbert von Buttlar who had called on Jantjes for help.[2] As far as Jantjes recalls, the show had a political agenda as foreign students apparently had been on the brink of losing their entitlement to benefit from the West-German state scholarship system (BAfög). Von Buttlar had intended to make a point about their importance for HFBK and beyond. But the show might also have been a demonstration of the academy’s efforts to respond to pressure from both the student body and teaching staff to create a more diverse institution.[3]

But what had motivated international students to move to Hamburg back in the 1970s? Jantjes, born in Cape Town in 1948, had been wanting to escape the dehumanizing politics to which the South African Apartheid regime had been subjecting its non-white population. A student of graphic design at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, a section of the University of Cape Town, since 1966, Jantjes relates that, possibly owing to his appointment as student representative and his involvement in protests against the university’s racist politics of appointment, he was threatened to lose the then necessary permission to study at a white institution.[4] The encounter with HFBK Hamburg student Barbara Luithard[5] who at that time also studied at Michaelis School of Fine Art led to her writing to her Hamburg professor, Hans Michel, who forwarded her message to von Buttlar. The latter offered Jantjes a place at HFBK Hamburg under the condition that he would secure himself a DAAD grant, which Jantjes, with von Buttlar’s support, successfully did.[6] In the winter semester 1970/71, he enrolled as a student in HFBK’s graphic design and visual arts departments.

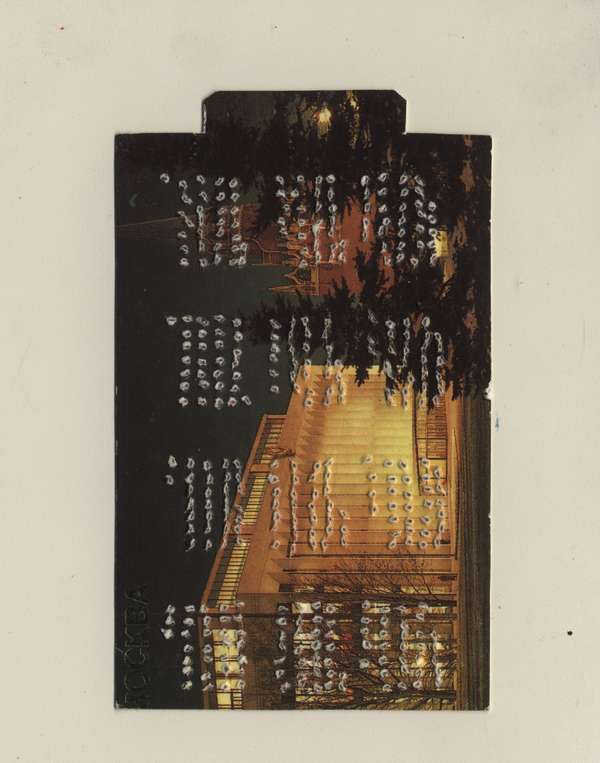

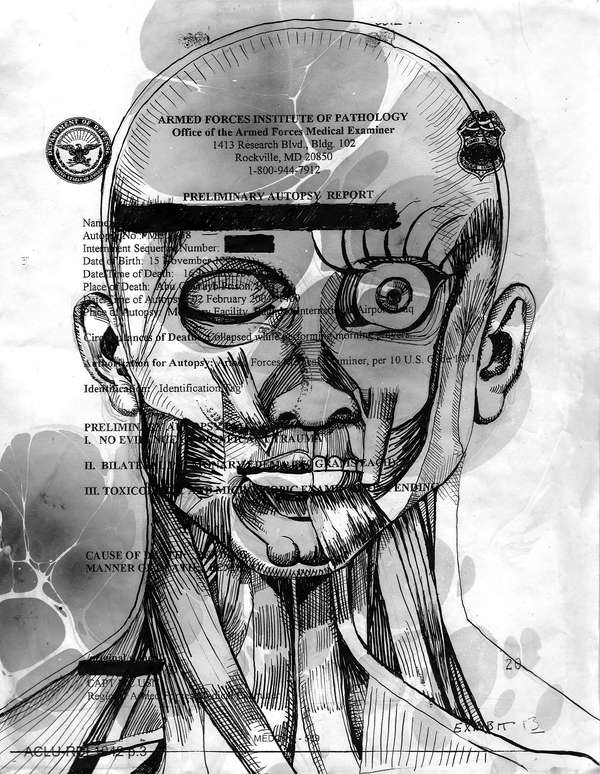

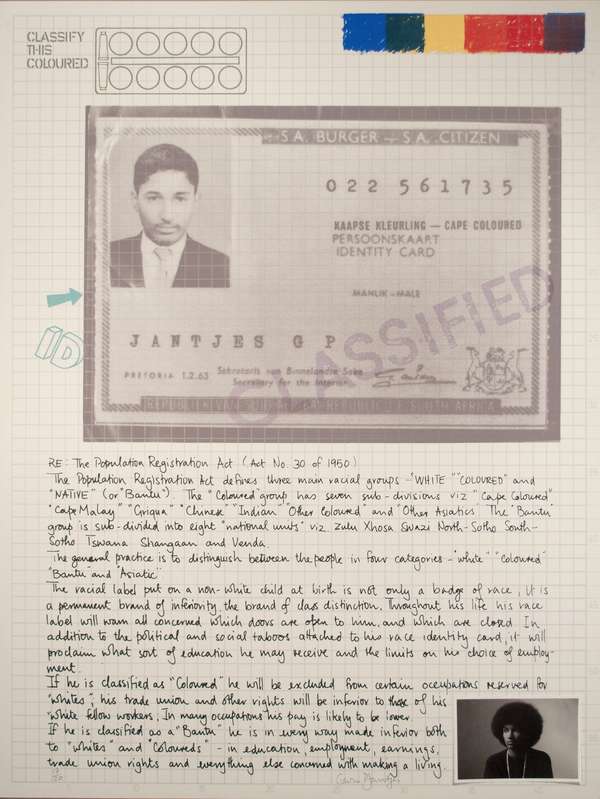

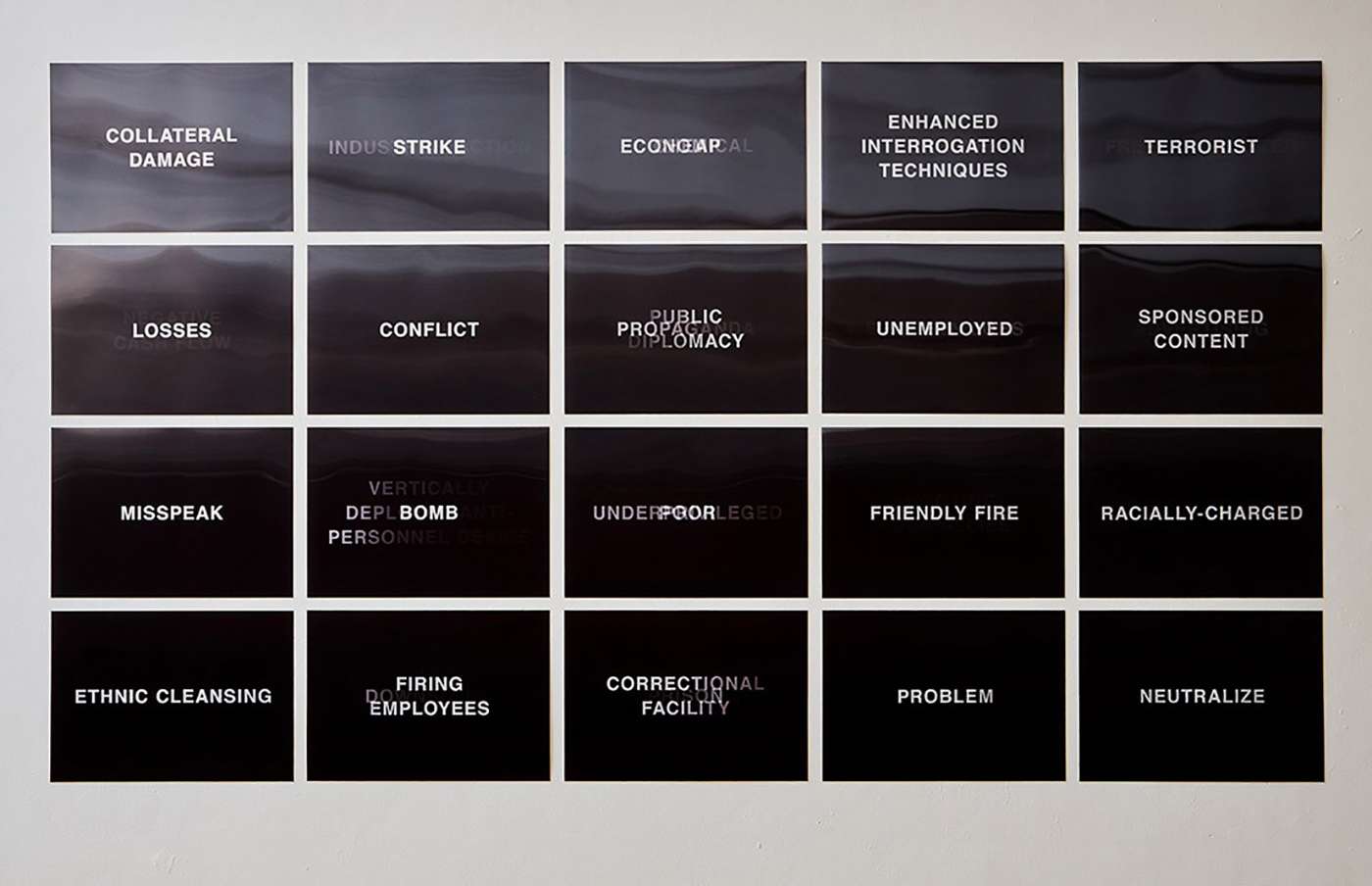

A few years later, in 1974, Gavin Jantjes was granted political asylum in West Germany, after some serious and troubling difficulties he had experienced regarding his residence status. Altogether it seems that Hamburg wasn’t the safe haven he had been hoping for. His artistic statement in the 1973 catalogue is very telling in that respect: “My work is an expression of my problems. The situation I am currently facing—Germany—is not so much different from the one I left behind—South Africa. Both bear the same racist traits, and every day, I am confronted with racial prejudice, racial hatred, and racist curiosity. I am presenting some parts of an unfinished graphic design project (I don’t have any money to complete it). I am calling it ‘colouring book.’ It consists of maps, sheets, objects, and games that convey information on people and things that, because of their color or their association with a particular color, are categorized / discriminated against.” (translation A.M.)

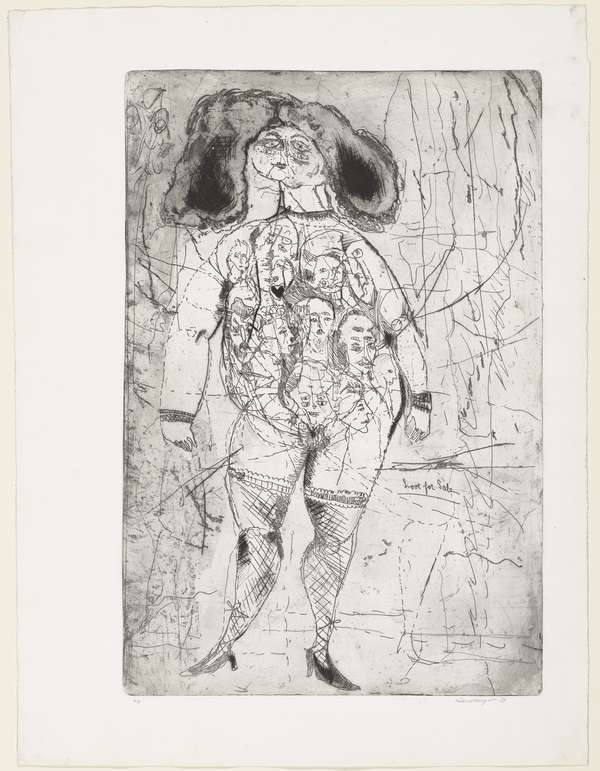

The work in question, now known as A South African Colouring Book, however, would retain what Jantjes referred to as its unfinished state. Apparently, he had planned to expand his acerbic didactics—the book strongly draws from the look of children’s educational tools—on racist politics and the subjugation of humans and land by white colonizers to create an artist book that would have included collages commenting on the struggles of America’s First Nations and the American Civil Rights movement.[7] There are, however, individual works dealing with these topics.[8] The Colouring Book’s twelve prints, though, all bearing individual titles and based on collaged photographs, newspaper clippings, drawings, and handwritten text, focus on the Apartheid regime’s institutionalized racism. The prints are arranged in a sequence along the notions of racial categorization, identity, labor, and state violence, exemplified via legislative texts, legal documents, and portraits of the country’s political leaders. Economic data and photographs depicting the inhumane working conditions of the mostly Black laborers, documents that speak of the segregation of people and public space, and press images detailing state violence against South Africa’s Black population provided further visual material for the work. All of this is interlaced with bitter personal comments by Jantjes himself and the odd Frantz Fanon quote. Some of the images Jantjes employed in this project were sourced from Ernest Cole’s photography book House of Bondage (1968), others from visuals by press photographers Peter Magubane and Sam Nzima.[9] According to Allison K. Young, in preparing for his project, Jantjes had travelled to London to browse the archives of the African National Congress headquarters and the office of the International Defense and Aid Fund.[10] Young also contends that the work was, at least to a certain extent, made in response to conversations Jantjes had with fellow students at HFBK Hamburg who didn’t seem to grasp the hopelessness of the situation of Black South Africans in the face of Apartheid.[11]

Jantjes’ Hamburg professors certainly also had a strong influence on the Colouring Book. Amna Malik in her essay on the work explicitly mentions Joe Tilson, who was a guest lecturer at HFBK Hamburg in 1971/72.[12] The parallels between Jantjes’ series and Tilson’s 1970 book project “Pages” with its combination of printed and hand-written text, complete with press images ranging from advertisements to portraits of civil rights and Black Power leaders, its superimposition of images or their Warhol-like repetition are certainly striking. According to Young, Joseph Beuys, guest professor at HFBK Hamburg for the winter term 1974/75, later invited Jantjes to participate in the Free International University exhibition at Documenta 6 in 1977 where Jantjes displayed the Colouring Book in a gallery adjacent to Honigpumpe am Arbeitsplatz.[13]

In 1970s South Africa, Jantjes’ work was banned. Especially in recent years though, with many a Western museums’ efforts to diversify, the Colouring Book has been included in a number of major museum collections, among them London’s Tate, which bought the work in 2002, and New York’s Museum of Modern Art, describing the book as a “recent acquisition.” One copy can also be found in Washington’s National Museum of African Art. Two editions went on sale at Sotheby’s 2020 online “Modern and Contemporary African Art” auction with an estimate of between 40,000 and 60,000 GBP.[14]

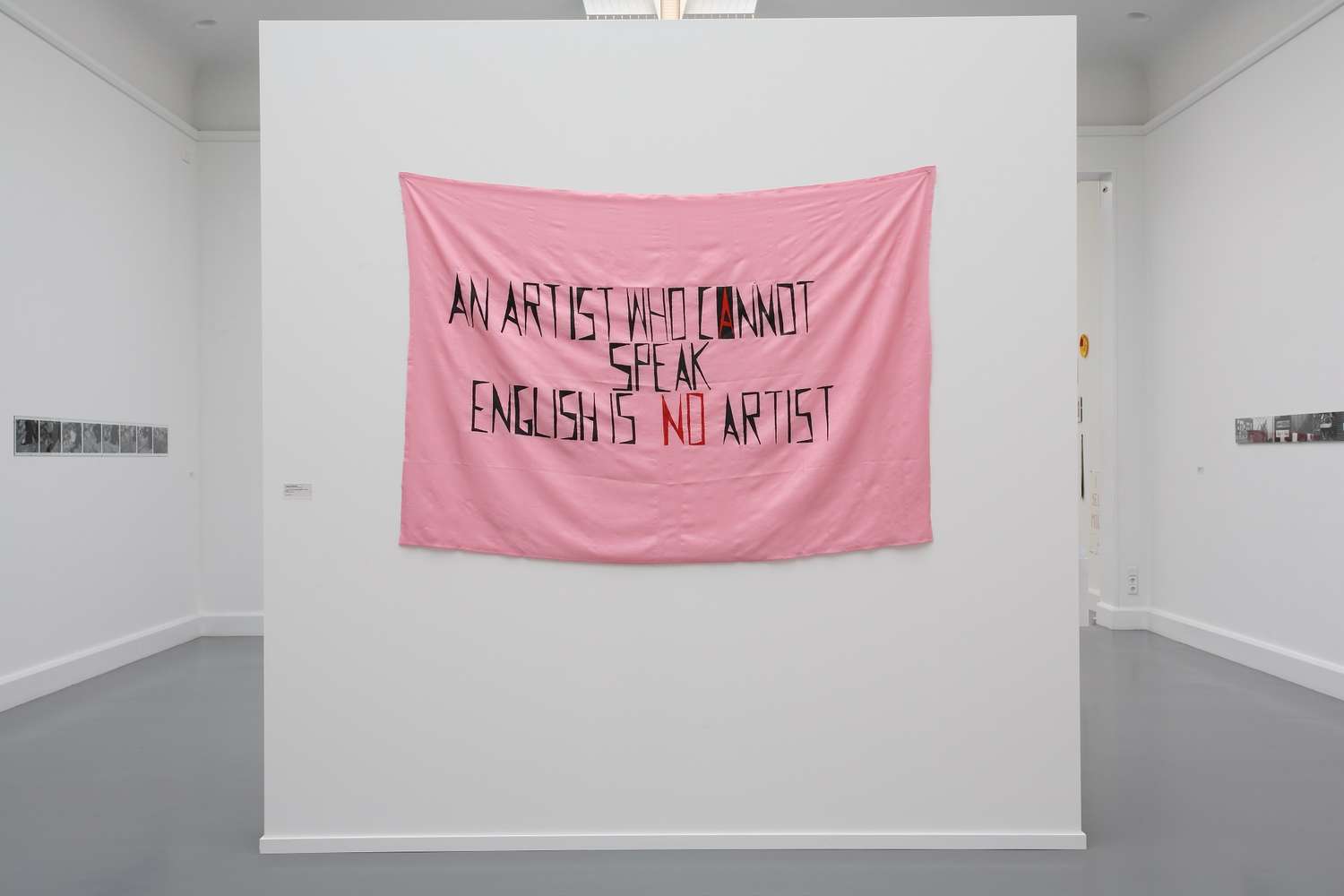

Today, Gavin Jantjes divides his time between Cape Town, England, and Oslo. Following his studies, he functioned as a graphic designer for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees before moving to Wiltshire, England, in 1982. He worked both in academia and was a member of various museum boards in London, until he was appointed artistic director of the Henie Onstad Kunstsenter near Oslo. From 2004 – 2014, he was Senior Consultant for International Contemporary Exhibitions at Oslo’s National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design. His artistic and political agenda hasn’t changed since 1973. In many of his subsequent artworks and also in his writing, Jantjes has alertly criticized racist structures and the instrumentalization or exploitation of non-Western cultures by white artists and curators.[15]

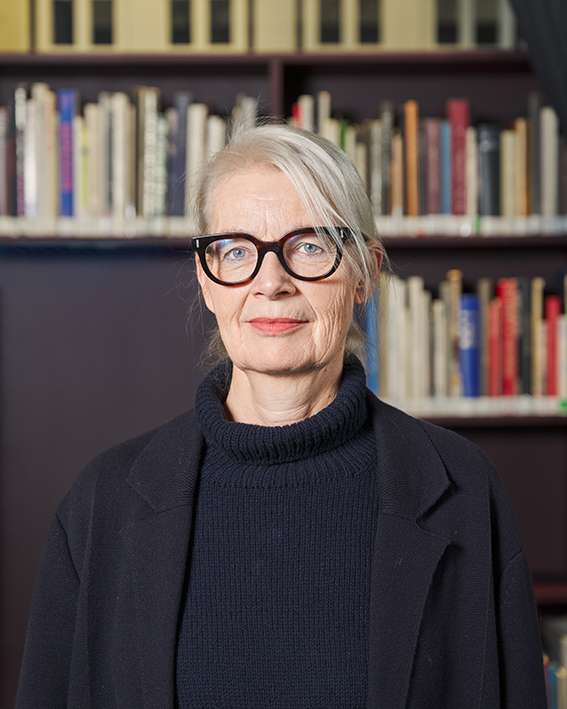

Dr. Astrid Mania is Professor of Art Criticism and Modern Art History at HFBK Hamburg.

Notes

[1] The author: “Narratives on Gavin Jantjes. His DAAD years at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste Hamburg 1970-72.” Online lecture (unpublished) in the context of the “Looking Back, Looking Forward. Artistic Itineraries Across African and German-speaking Countries in the 1950s to 1970s” symposium at Kunsthistorisches Institut der Universität Zürich, December 16/17, 2021.

I would like to thank Gavin Jantjes for his generosity in sharing his recollections with me in preparation for the lecture. Unfortunately, he was not available for an interview for Lerchenfeld, so this essay comes in lieu of a conversation. I have not quoted from any of the emails Gavin Jantjes sent me in late 2021, but I have been drawing information from them and have tried to do so in the most respectful manner.

[2] Who took up the challenge, together with Argentinian-born fellow-student Luis Siquot. Gavin Jantjes in an email to the author, Dec 1, 2021.

[3] ibid.

[4] Gavin Jantjes in an email to the author, September 4, 2021.

[5] Barbara Luithard, accompanied by her husband and former HFBK Hamburg graphic design student Rudolf Luithard, had spent some years in South Africa where she had also studied at the Michaelis School of Fine Art’s design department before resuming her education at HFBK Hamburg.

[6] Gavin Jantjes in an email to the author, September 4, 2021.

I have not been able to retrieve any information from DAAD as to whether there may have been any special support for academics who were victims of the Apartheid regime. On a broader political scope, the West German government under Willy Brandt maintained close economic relations with the Apartheid regime.

[7] Gavin Jantjes in an email to the author, Dec 1, 2021.

A South African Colouring Book comes in an edition of 20. The sheets are kept in a black folder that has on its cover the work’s title and the emblematic, stylized color palette that recurs on every print. They each measure 60.2 x 45.2 cm.

[8] For instance, The First Real Amerikan Target (1974, color lithograph with collage, 59 x 44 cm) with its portraits of First Nation leaders shown above a colorful target, a sarcastic appropriation of Jasper Johns’ Target with Four Faces (1955).

[9] Allison K. Young. “Visualizing Apartheid Abroad: Gavin Jantjes’s Screenprints of the 1970s.” Art Journal. Vol 76, Fall-Winter 2017, pp. 10 – 31, 15.

[10] Ibid., p. 14. This is in line with Jantjes’ description of the work for the Sotheby’s 2020 online sale Modern and Contemporary African Art catalogue (June 4, 2023).

[11] Young, op. cit., p. 14. In the 1973 catalogue, Jantjes is first among the students who introduce themselves as “Gruppe ‘Black Students’,” calling on the visitors to benefit from the opportunity to meet the group and listen to their problems.

[12] Amna Malik. “Gavin Jantjes’s A South African Colouring Book.” Nick Aikens and Elizabeth Robles The Place is Here, The Work of Black Artists in 1980s Britain, ed. Berlin: Sternberg Press 2019, pp. 161 – 190, 182.

[13] According to Young, “Jantjes sat in the gallery, speaking with visitors and giving impromptu lectures about his work.” Young, op. cit., p. 18.

[14] Unfortunately, the results are not disclosed. However, under lot 79, Sotheby’s publishes the above-mentioned description of the work by Jantjes himself, even though the date of the work’s display at HFBK is erroneously stated as 1974. See fn. 9.

[15] See, for instance, his doubtful remarks on the 1989 exhibition Magiciens de la terre with its self-proclaimed equality between all participating artists, regardless of their background: Gavin Jantjes. “Red Rags to the Bull.” Rasheed Araeen (ed.). The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain (exhibition catalogue), London: Hayward Gallery, 1989, unpaginated.

This article appeared in Lerchenfeld issue #67.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Long days, lots to do

Long days, lots to do

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

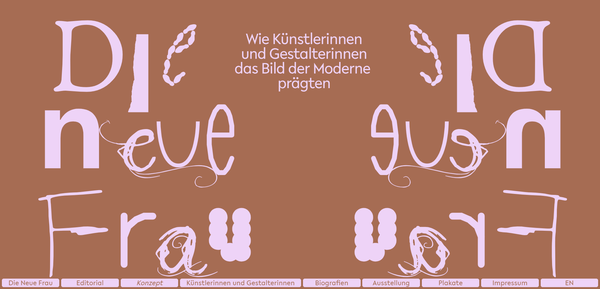

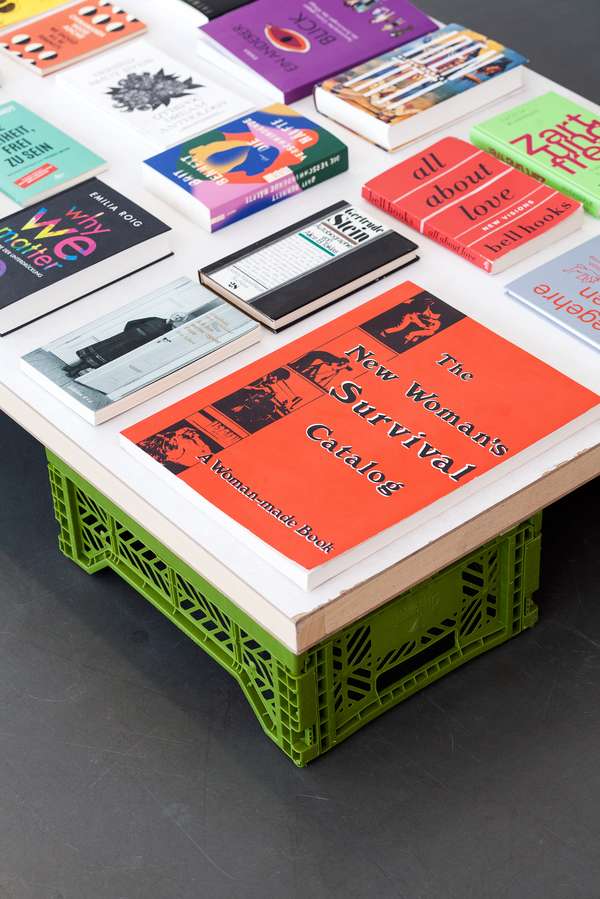

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

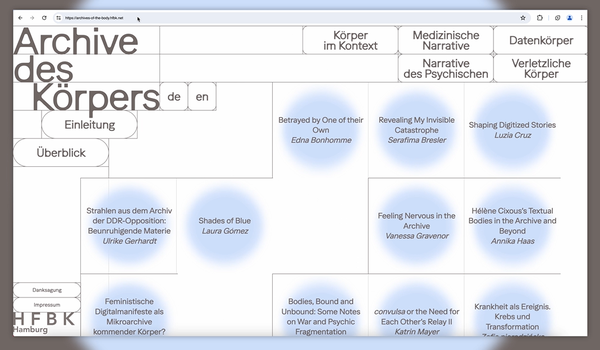

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

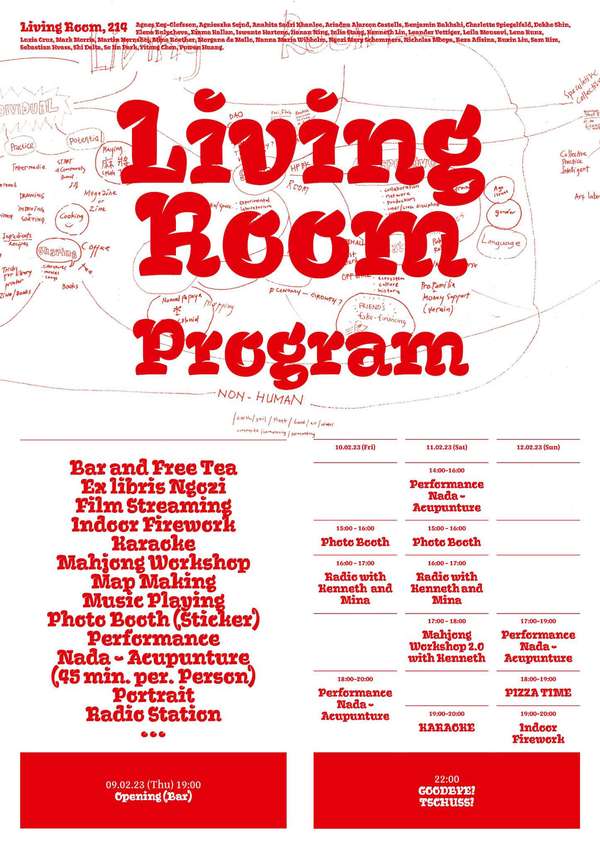

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

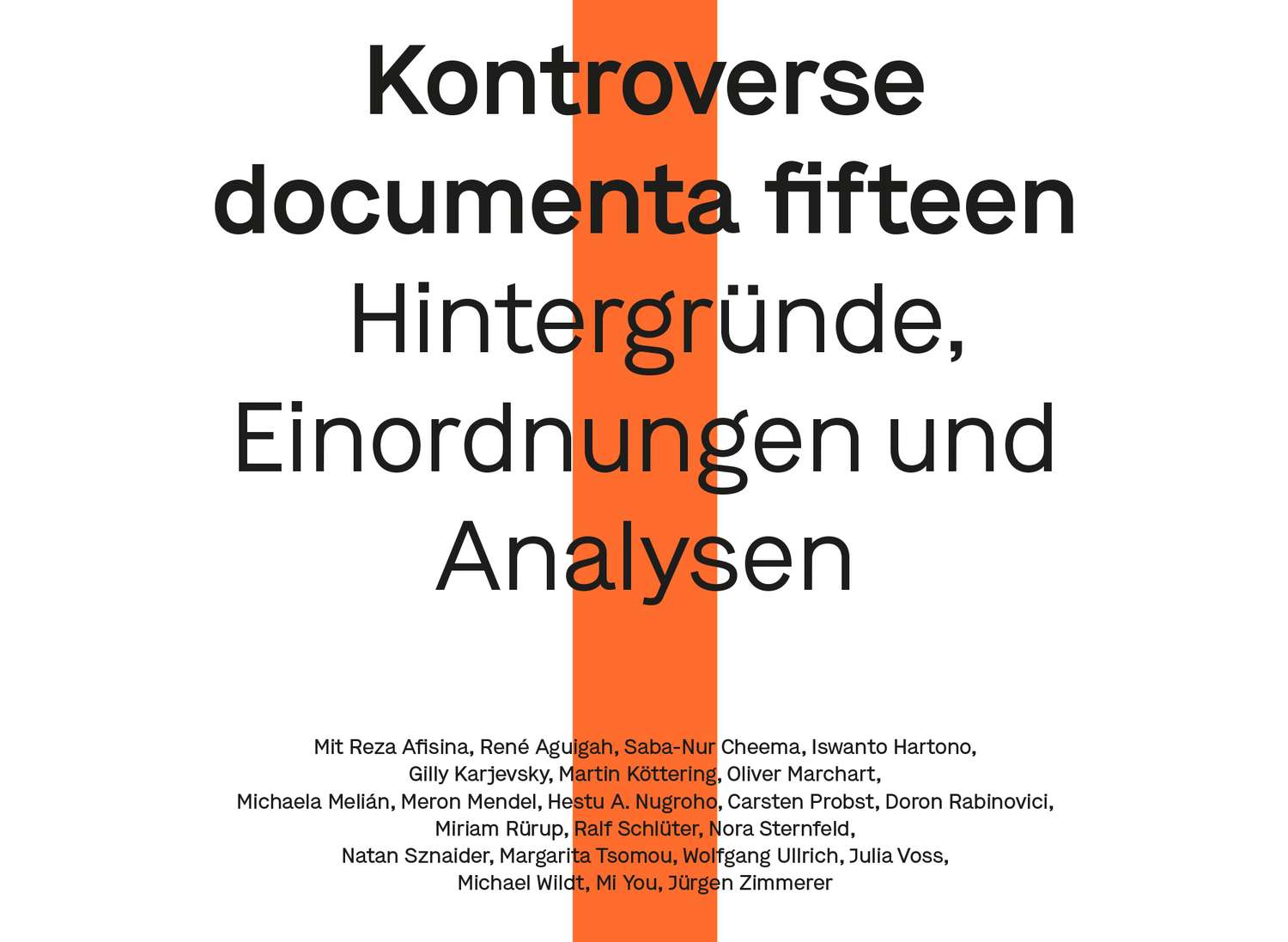

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

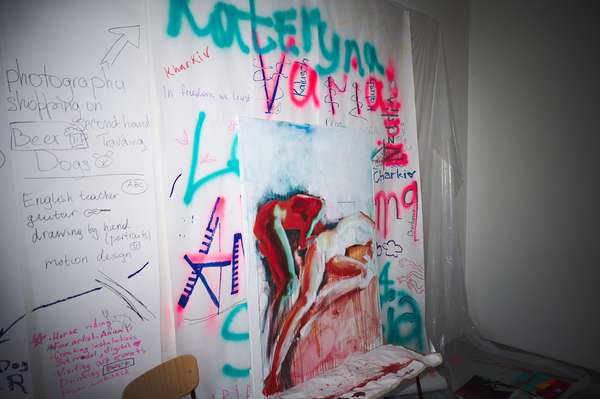

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

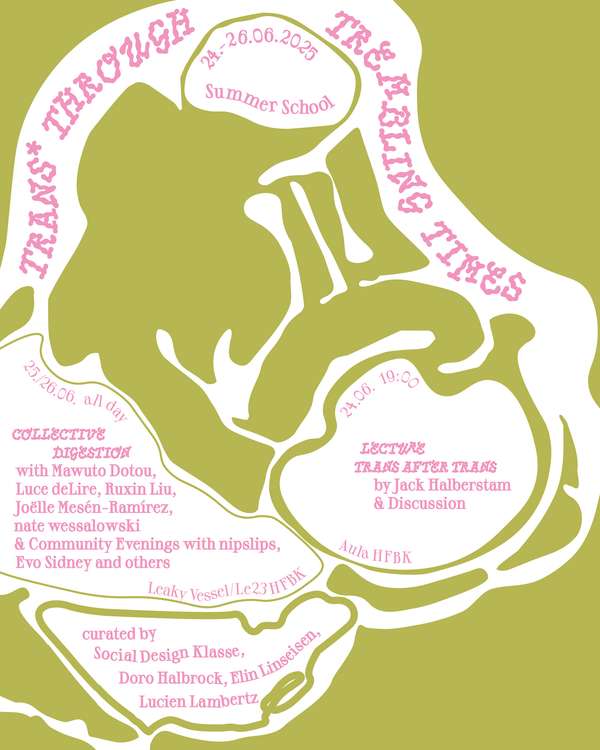

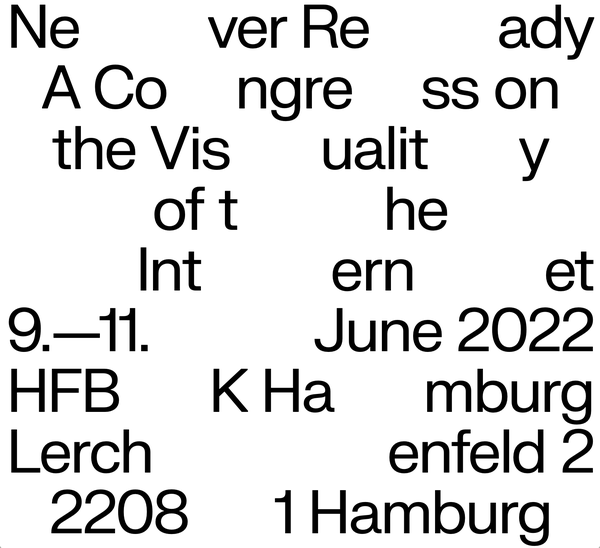

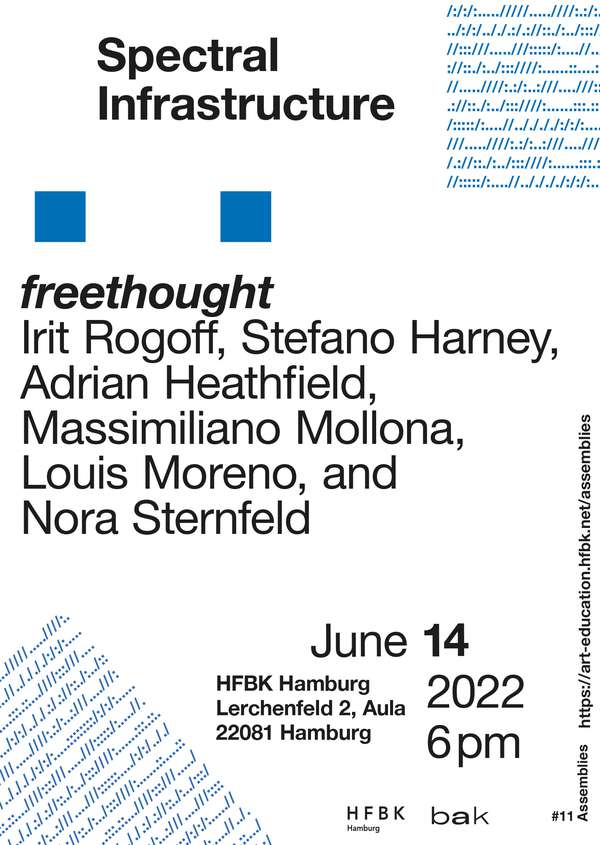

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

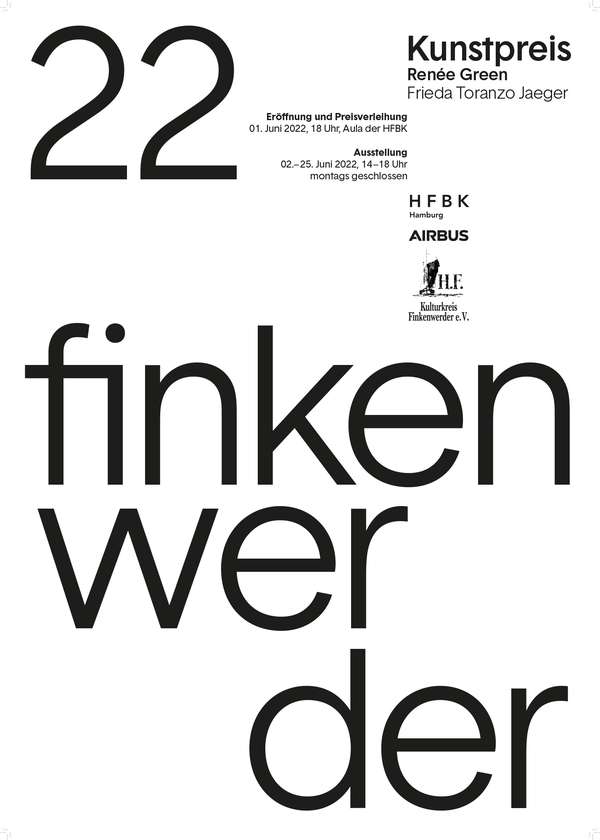

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

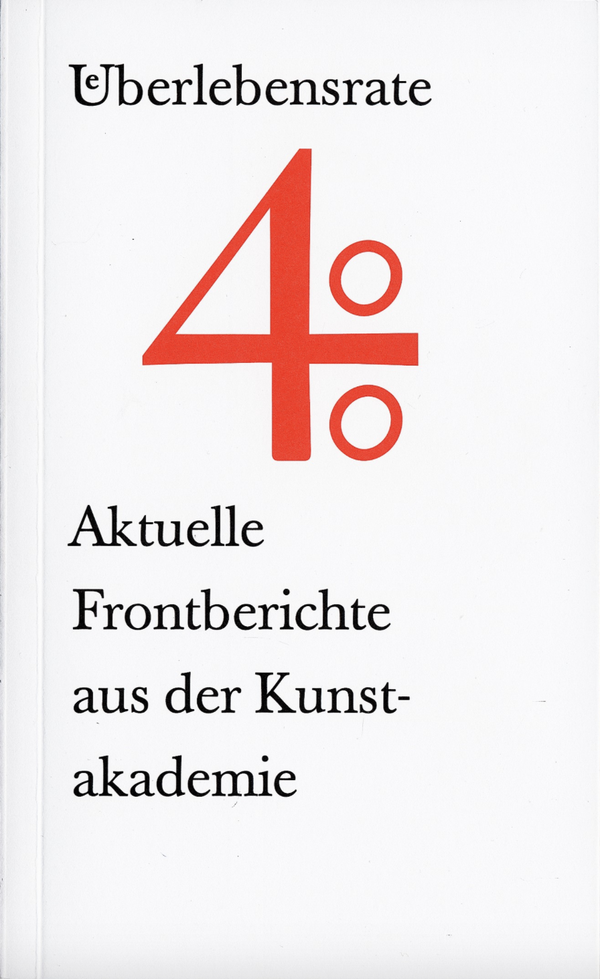

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

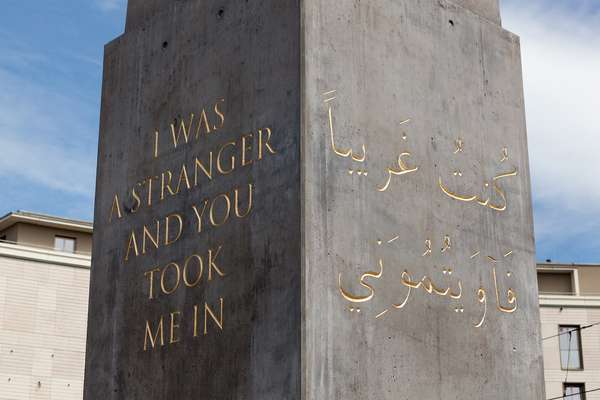

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Diversity

Diversity

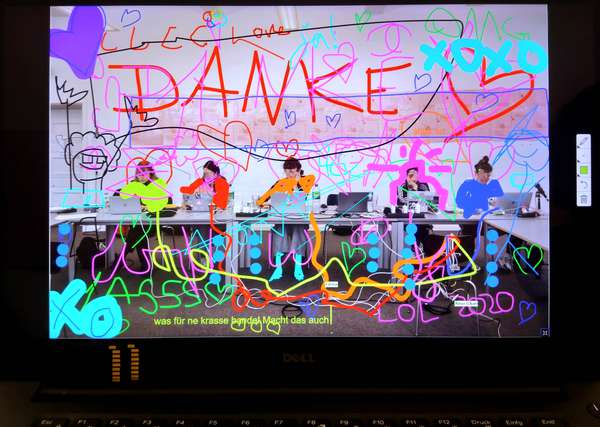

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

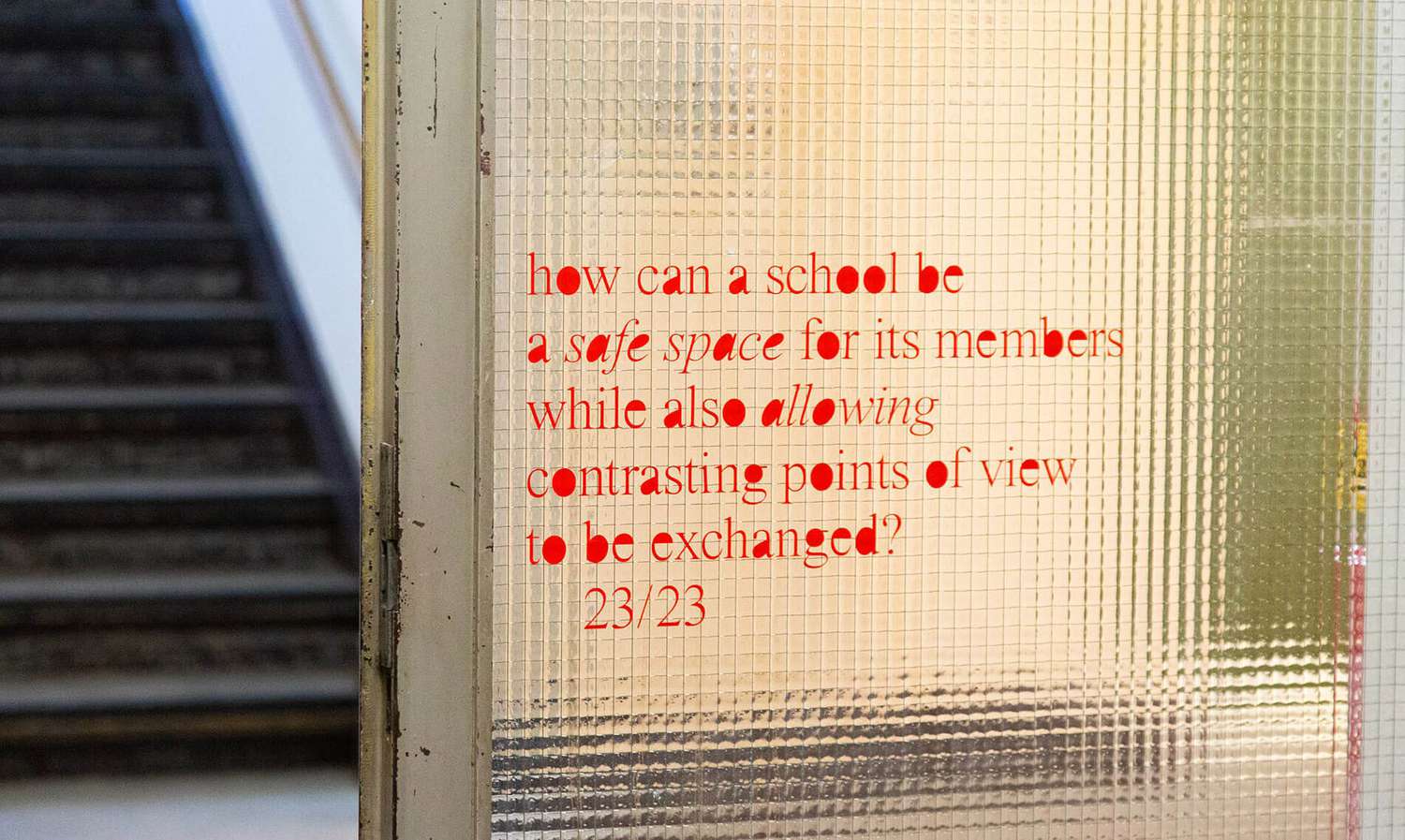

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

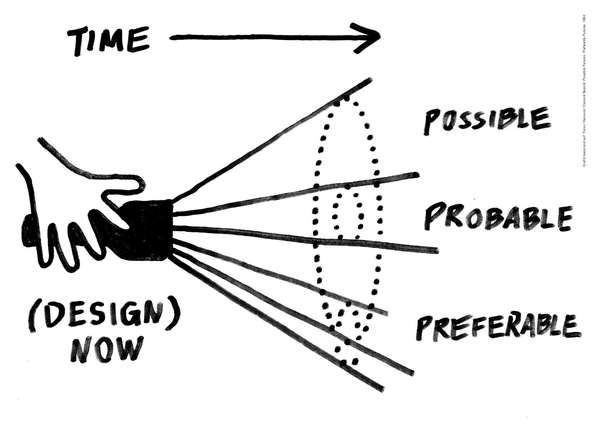

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?