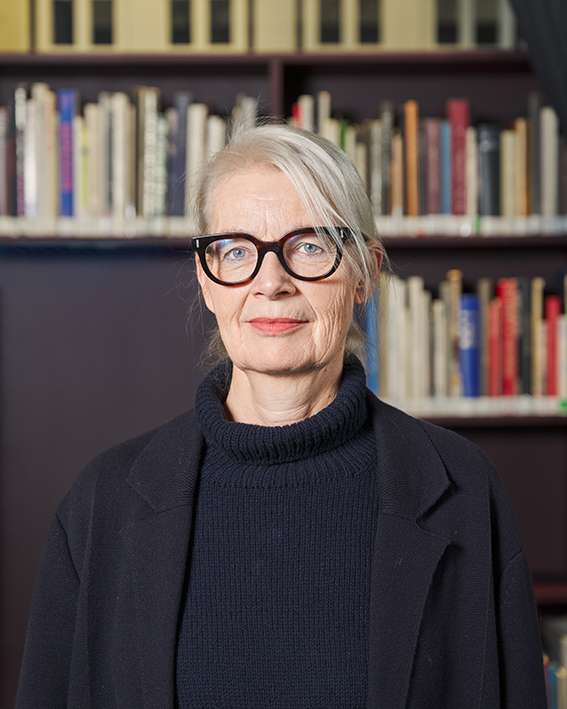

What do you actually do? – Mirjam Thomann

“I just want to say that I didn’t prepare for your visit,” says Mirjam Thomann as I step into her impeccably tidy studio. Glancing towards shelves of cardboard boxes ordered by project and date, Thomann’s filing system does look suspiciously neat, but the Berlin-based artist, writer, and educator quickly explains that years spent working as a studio assistant taught her the importance of running a tight ship. “I noticed how lost artists are if they didn't have an organized archive, so I decided to start early,” she explains. “At the beginning every exhibition or every major work had a box on its own, but it’s funny to see how digitization means that every year the boxes are getting smaller and smaller.”

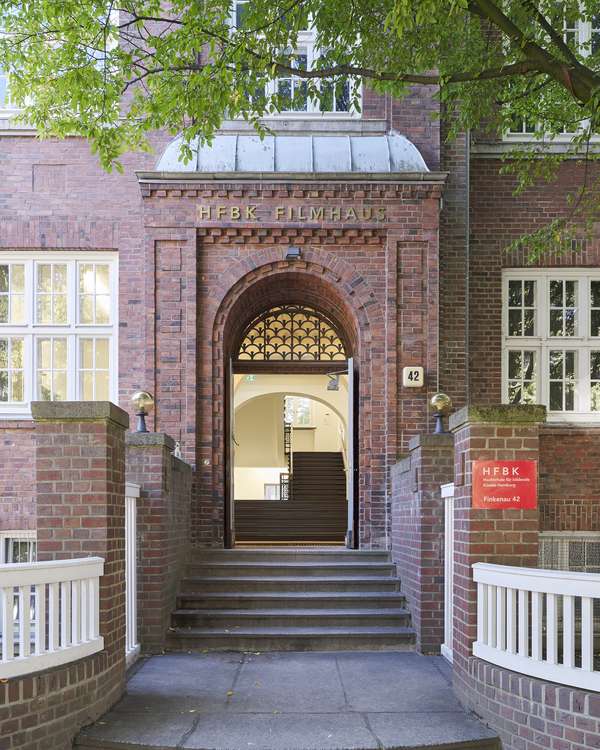

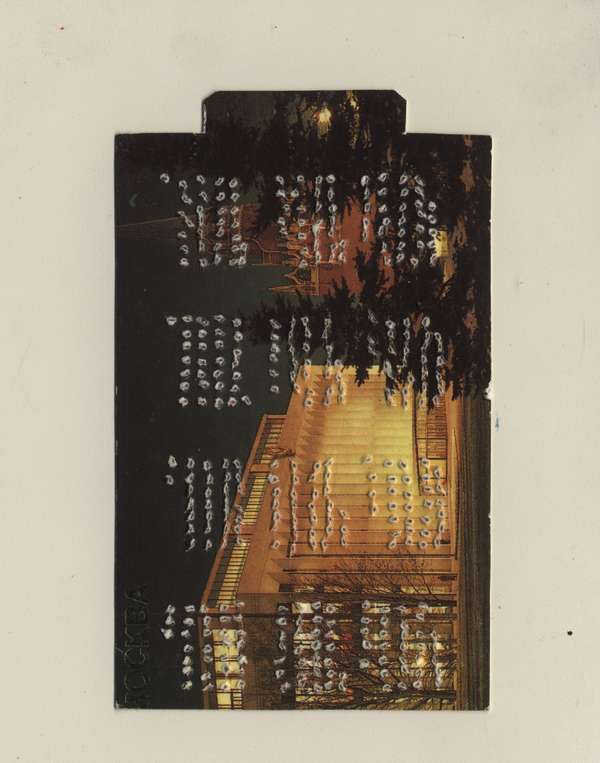

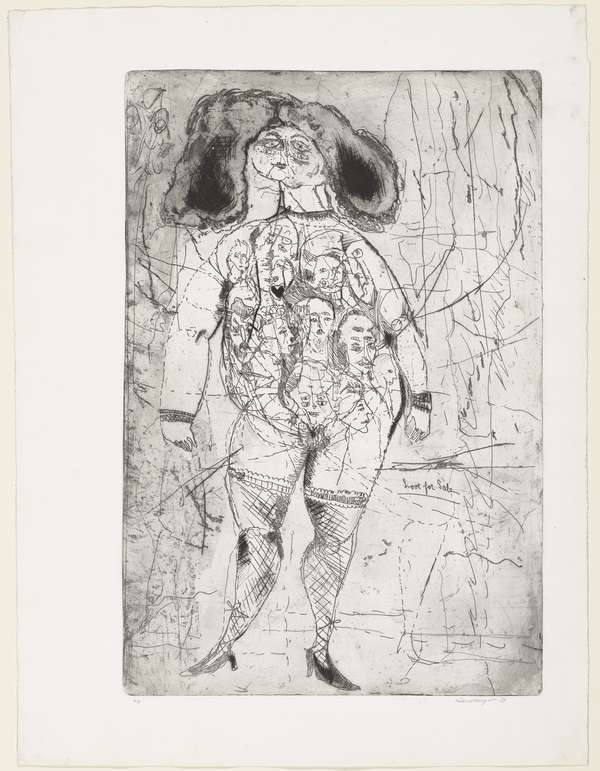

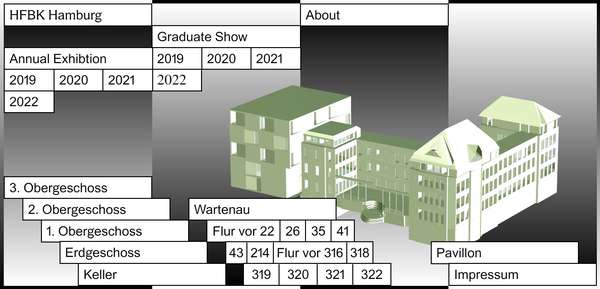

Other than marking the passage of time, this methodical approach to documentation offers Thomann a bird’s-eye view of her fifteen-year practice, enabling the Wuppertal-born artist to trace a clear thematic line from her earliest exhibitions right up to the present day. Pulling out a stack of publications and flyers from the shelves, Thomann shows me an image from a 2005 group show at the Galerie der HFBK, for which she installed a revolving door at the entrance to the space. “I think this is the first work I did where I was referring to and intervening in a concrete situation in the architecture,” she explains. “Already I was starting to think about who is included in the art system. Who is allowed to enter the space? Who’s got the social or economic ability to become part of what we're doing and how can we alter that as artists?”

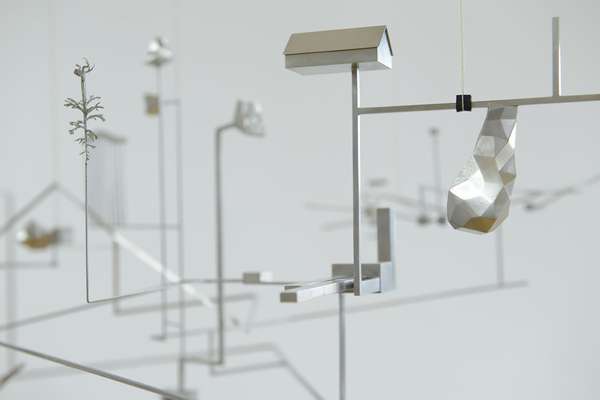

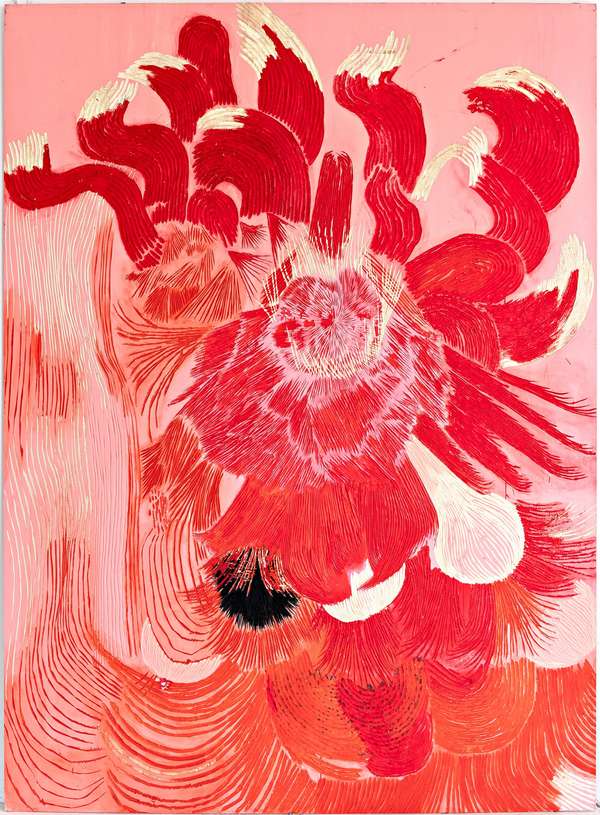

Although her output has become more refined over the years, Thomann continues to work site specifically, often creating sculptures that function as extensions of the space they are shown in. At her 2018 solo exhibition at Galerie Nagel Draxler, for example, Thomann included a series of rotatable corner pieces painted in the same off-white as the gallery’s walls. Alongside these moveable sculptures, she also placed mirrors, text fragments, collapsible chairs, and negative prints made from ceramics in flesh-colored tones. With generic titles such as Chair I and Corner Piece II, for Thomann, the focus was less on these individual pieces than in their relationship with each other. “The interaction between the space, the object I put into it, and the bodies of the visitors moving through the installation is a dynamic I'm always interested in,” she explains.

As a regular contributor to Texte zur Kunst, Thomann has written a number of texts on this topic. Her 2020 piece “The Feminist’s House,” for instance, imagined what an emancipatory approach to architecture could be. Written in epistolary form, the text is, in many ways, a love letter to those who have influenced her thinking about gender identity and build environments. “It’s very much a cut and paste text,” Thomann explains. “It’s based on quotes from artists, theorists, architects, and horoscope writers who said anything that I found interesting about the enactment of architecture. The idea was to put multiple voices together in a performative way rather than create a liner argument.”

More than just a theoretical engagement, Thomann’s writing is influenced by and feeds into her sculptural work practice. Her text “Woman and Space,” for instance, came directly out of her experience of making Lean In 1-3, a sculpture series developed for the North Coast Art Triennale in 2016. Comprising of three flesh-colored steel structures placed within a pastoral landscape in Gibskov, Denmark, the sculptures offered visitors a place to lean and smoke into the attached ashtrays while taking a break from viewing artworks. “I’m not only interested in thinking about space but asking myself what sculptural interventions could make space accessible in different ways,” says the artist.

Whether shown in a park or a gallery, Thomann’s works are almost always placed within the margins of a given space. “Most the pieces I do are positioned in the corners or entrances and exits of a room,” she explains. “I hardly ever use the center of the area I’m working in.” Drawn to what she calls “transitional spaces,” such as doors, walkways and stairs – “anything that leads you from one area to the next” –, Thomann sites the late architect Lina Bo Bardi as a major influence on her practice. Alongside the iconic spiral staircase Bo Bardi created for Solar do Unhão in Brazil, which combines beauty with functionality, Thomann also finds inspiration from the Italian Brazilian architect’s glass and concrete exhibition display from the 1960s for the São Paulo Museum of Art. “Paintings were hung so that it looked like they floated in midair,” she explains of the radical design. “Bo Bardi really broke down the hierarchies between space, painting, and viewer.”

Bo Bardi’s example will no doubt be on the artist’s mind as she prepares for her next project: creating a sculptural work that can also function as an exhibition display for a group show at the Kunstraum of Lüneburg University. Planned for September, Thomann is excited by the challenge of creating a functional sculpture that still keeps its status as an artwork. “It’s a great opportunity to bring together a lot of themes that have been coming up in my work over the last 15 years,” she says. “Creating objects that have transitional characteristics or celebrate a certain in-betweenness is something that has been present from the very beginning.”

Mirjam Thomann is an artist based in Berlin. She studied at HFBK Hamburg from 2000 to 2006 with Profs. Eran Schaerf and Sabeth Buchmann. From 2018 to 2020 she has been a visiting professor for Sculpture at the Kunsthochschule Kassel. Her work is represented by Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Cologne.

HFBK graduate Chloe Stead, together with the photographer and also HFBK graduate Jens Franke, met former HFBK students to talk about work, life and art. It is the prelude to a series of interviews for the website of HFBK Hamburg.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

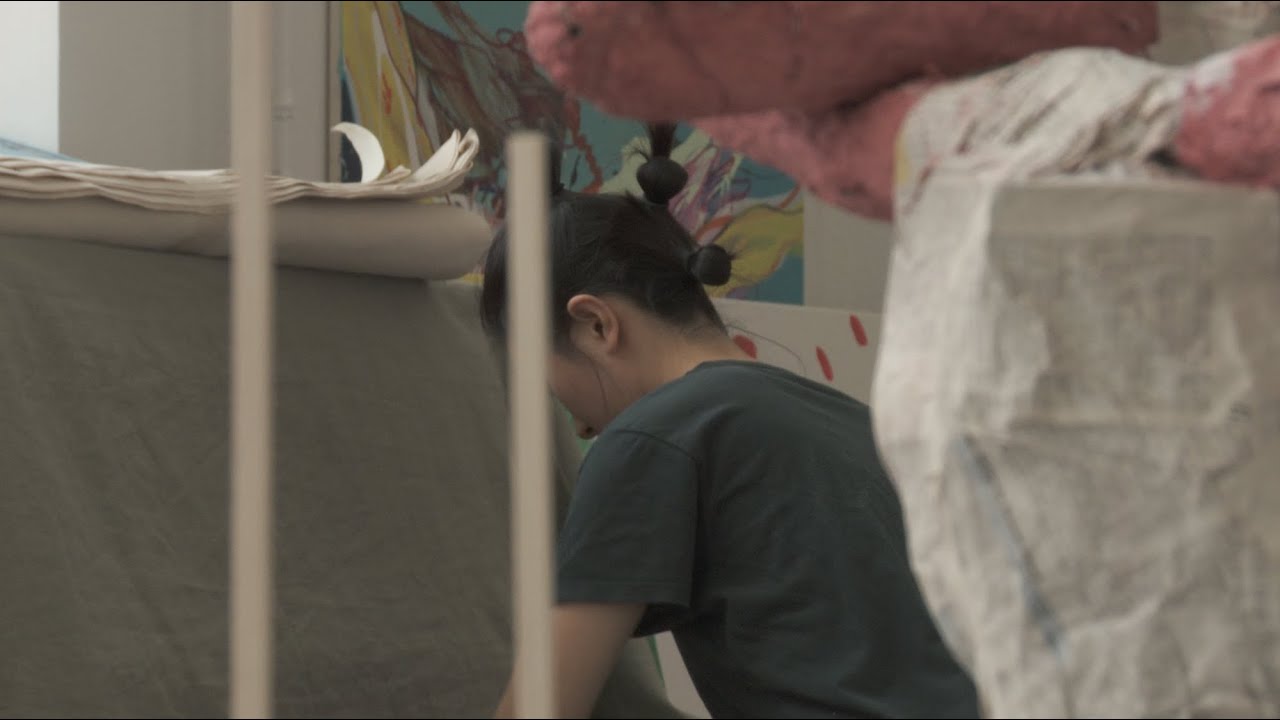

Long days, lots to do

Long days, lots to do

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

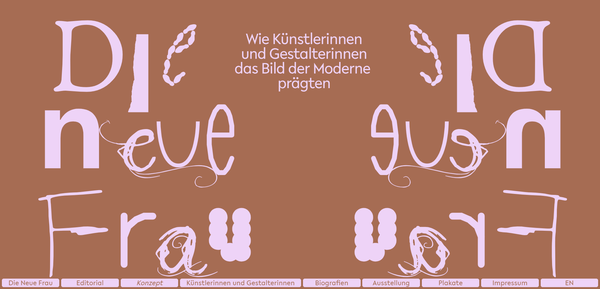

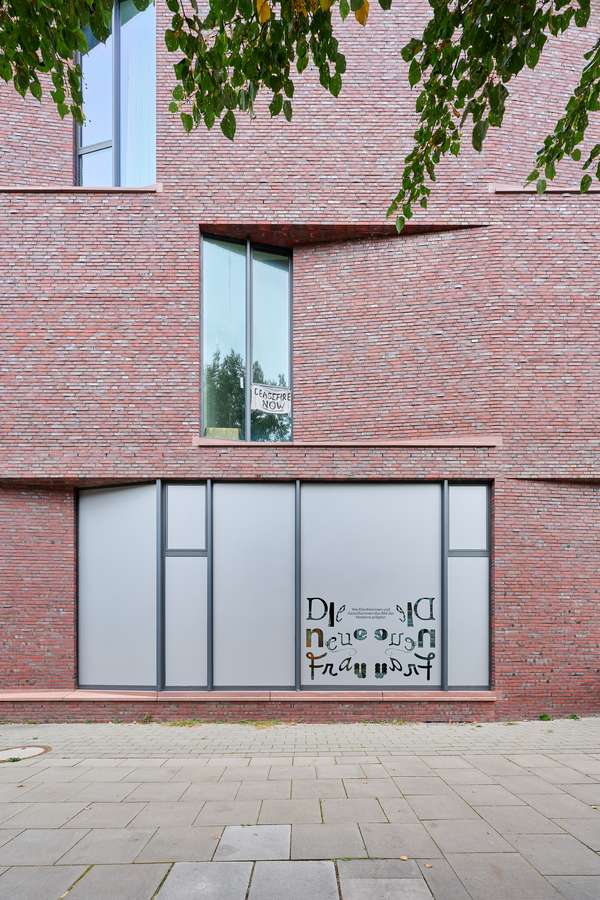

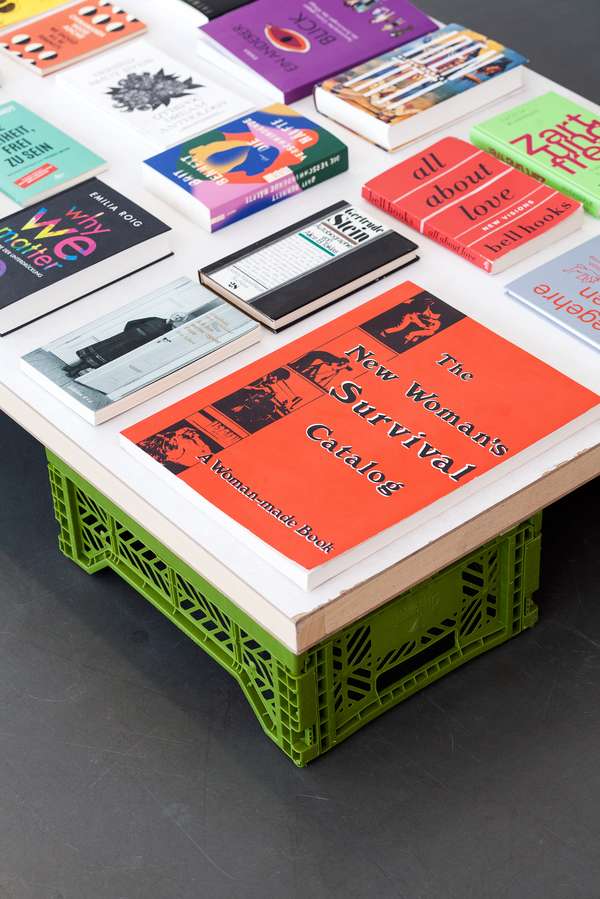

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

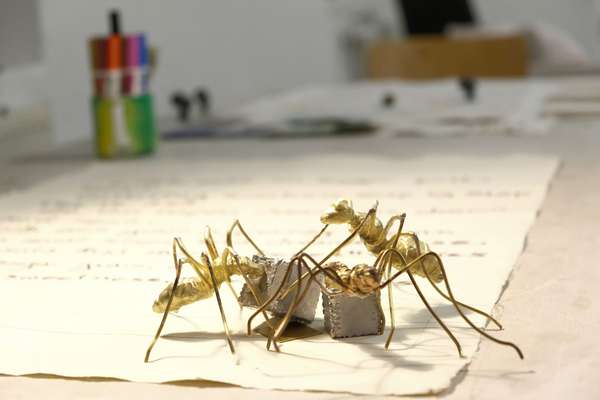

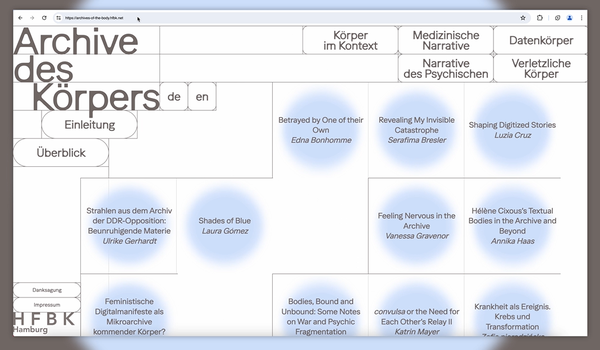

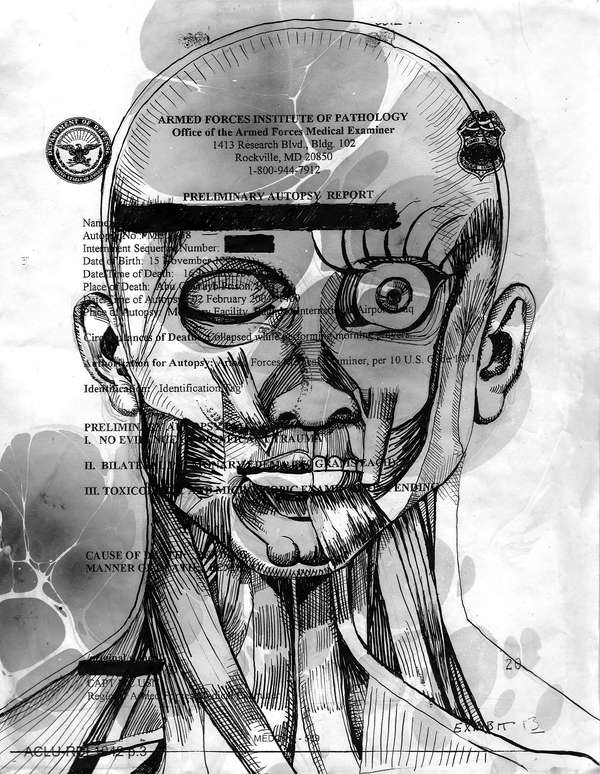

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

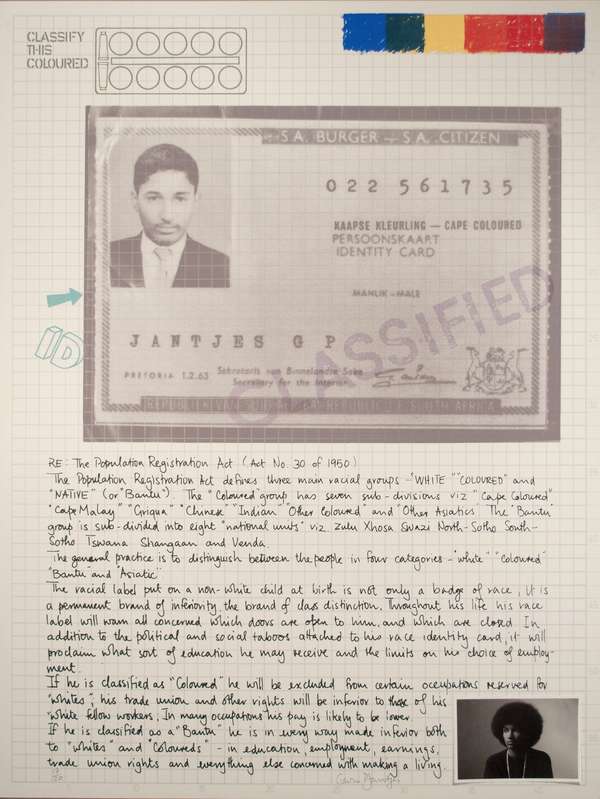

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

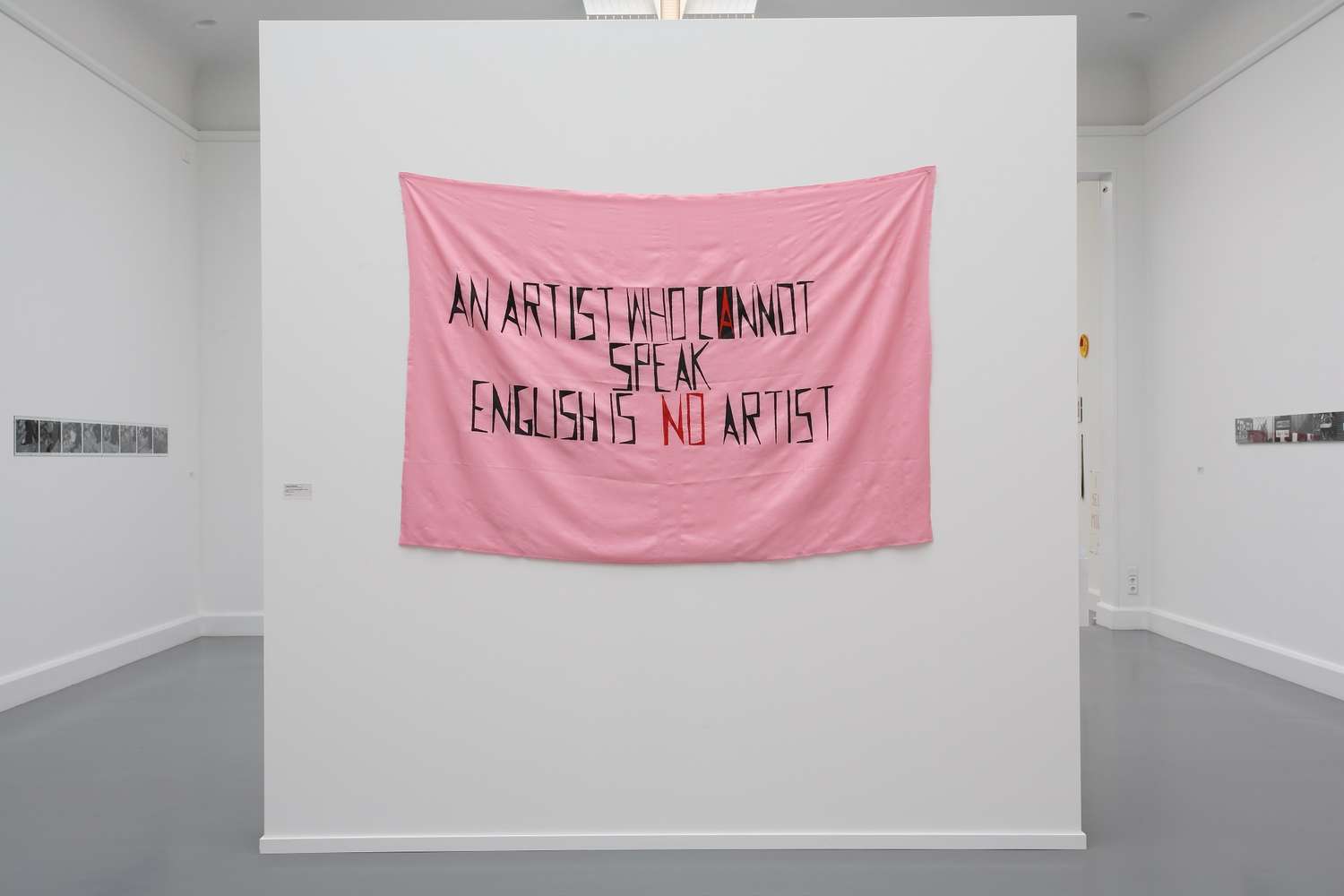

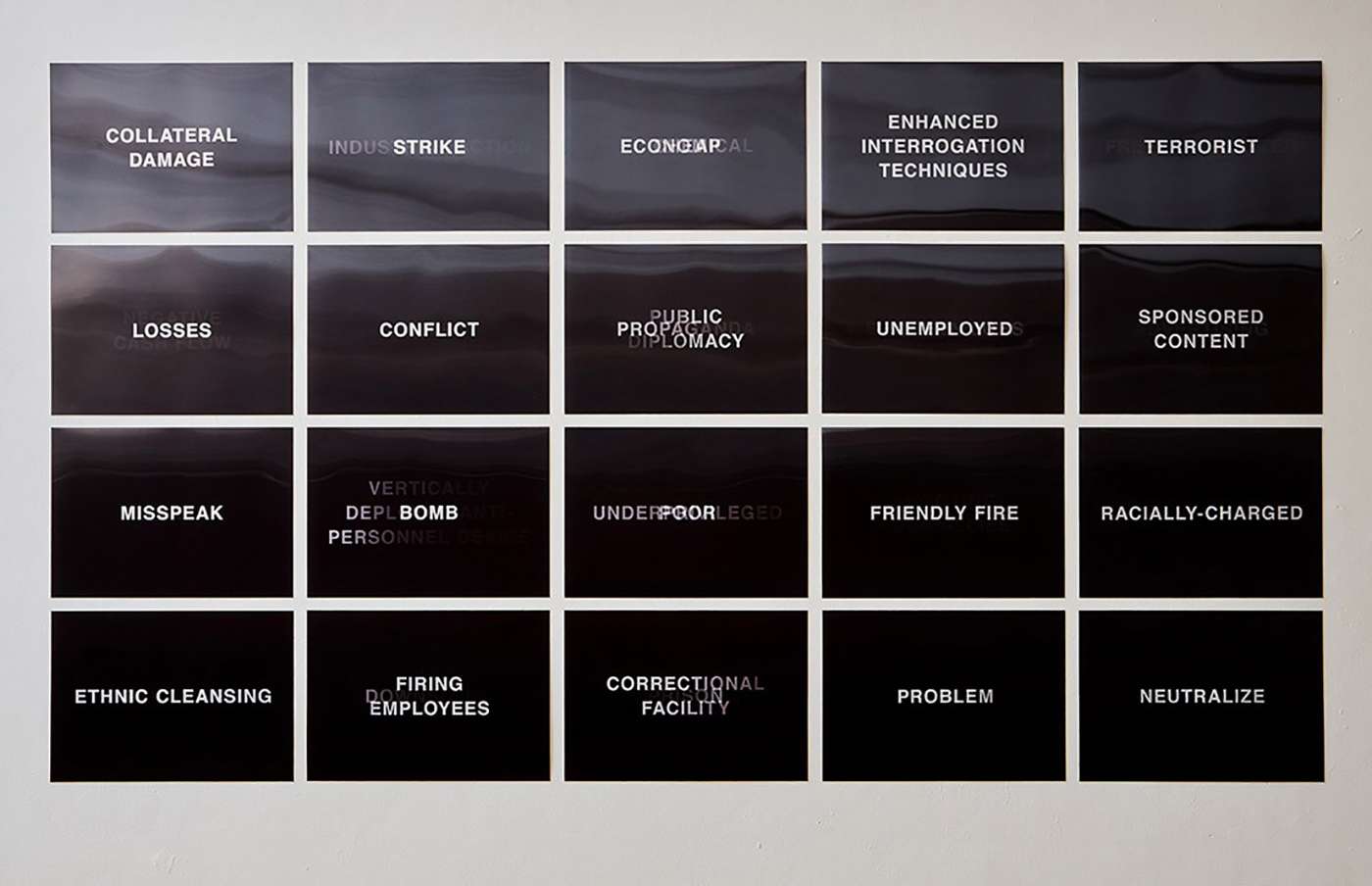

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

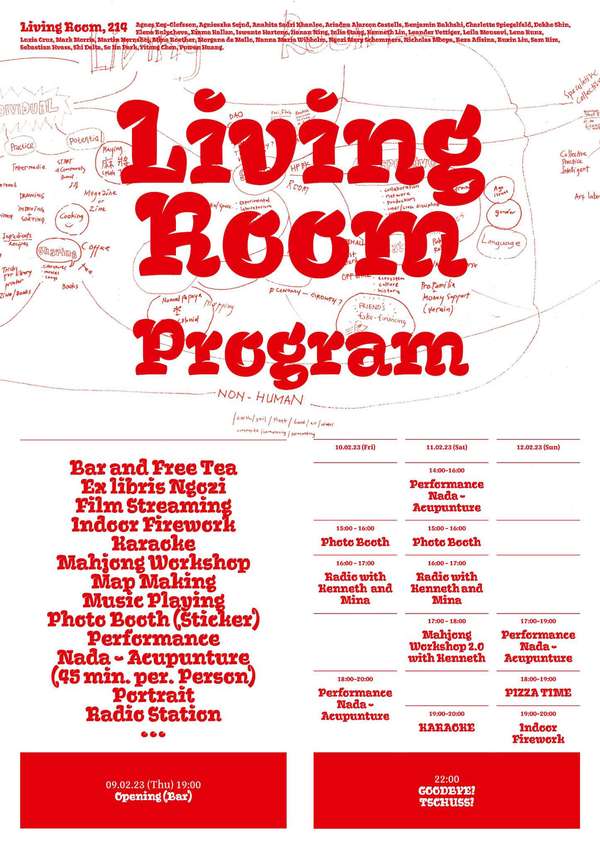

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

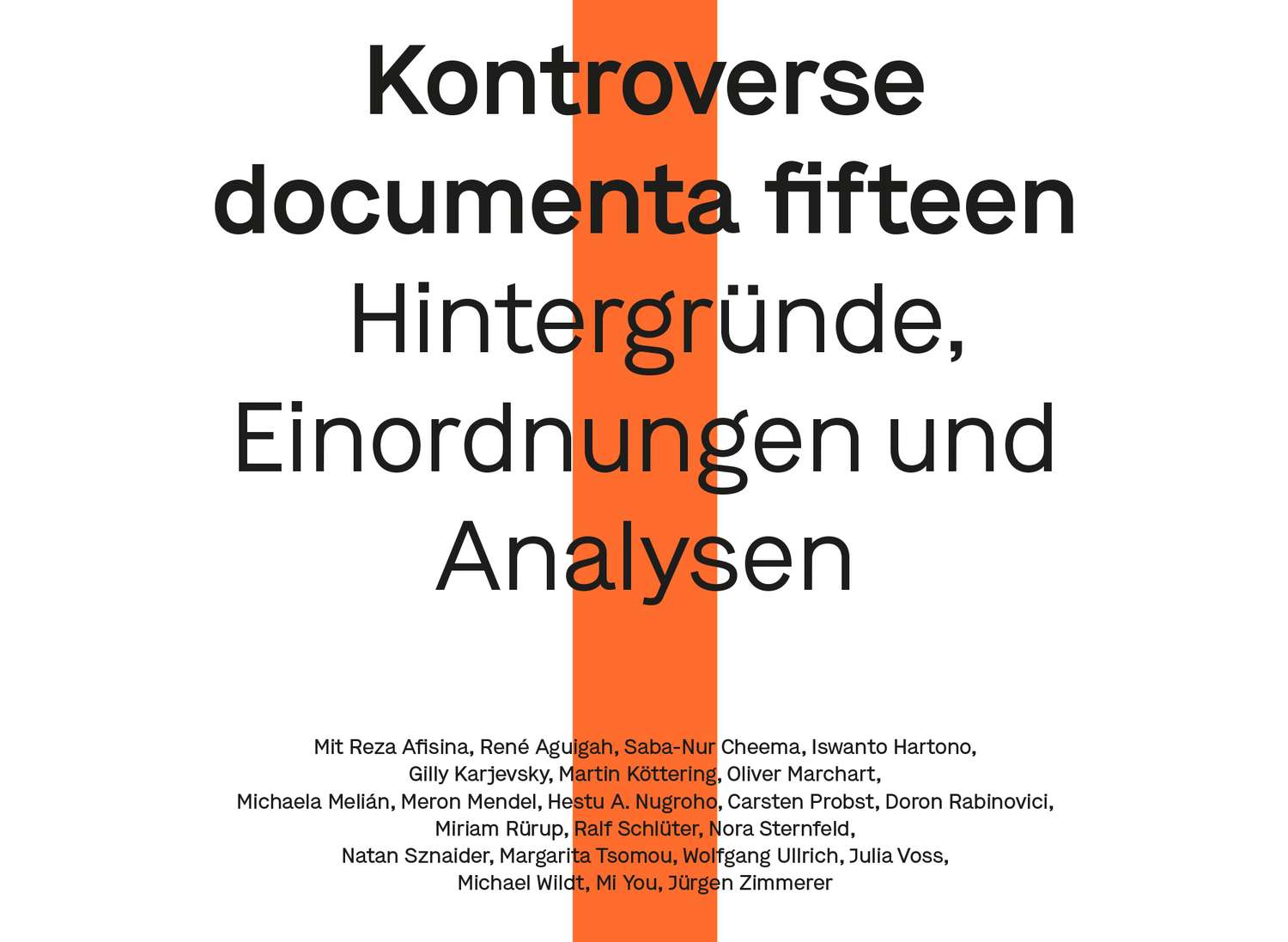

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

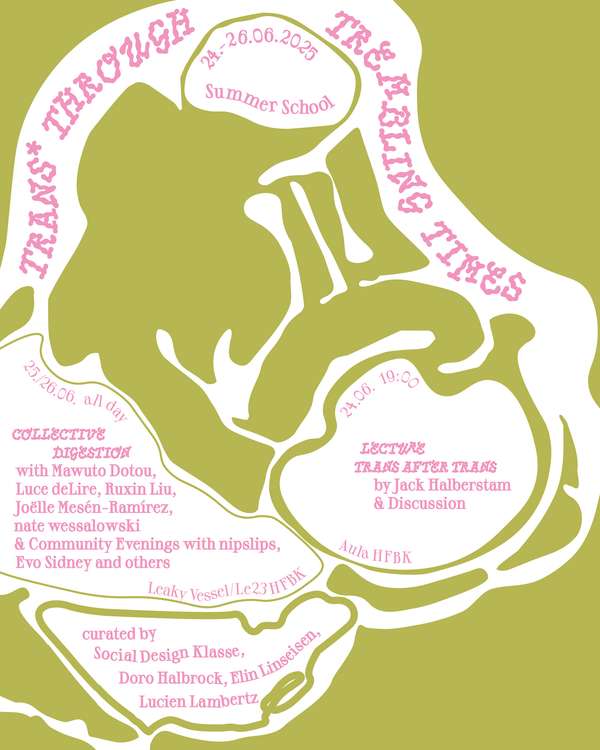

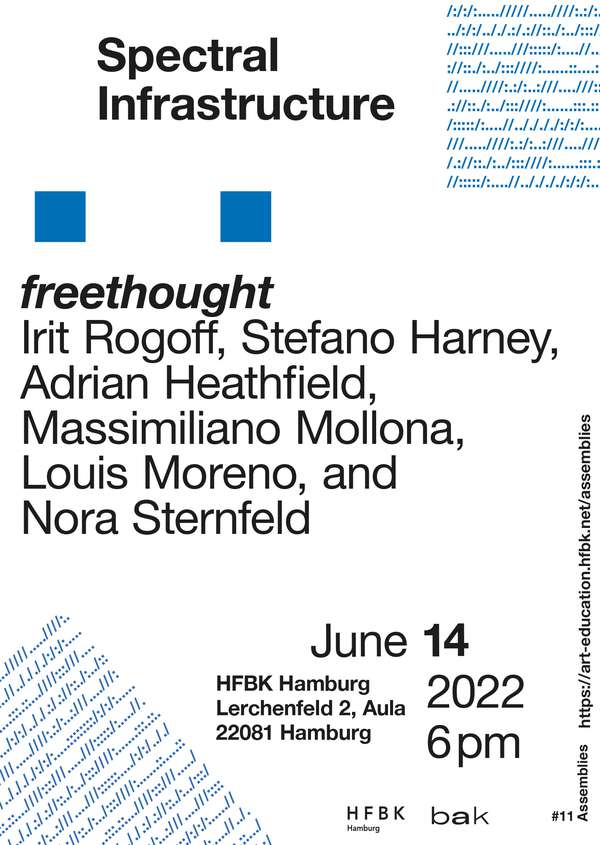

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

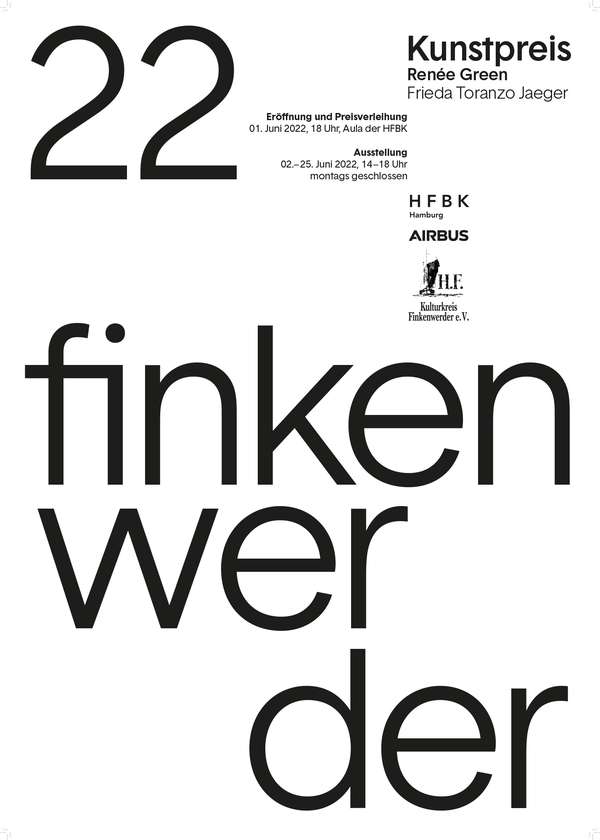

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

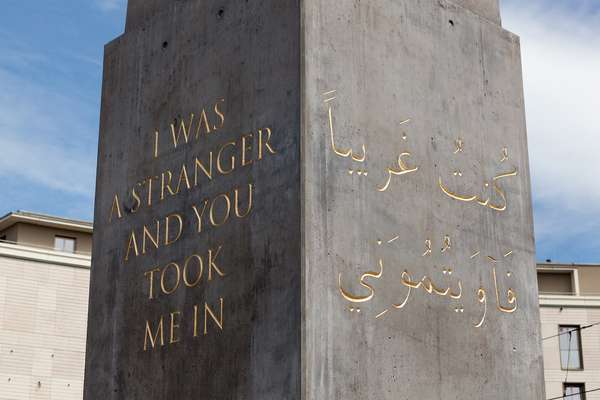

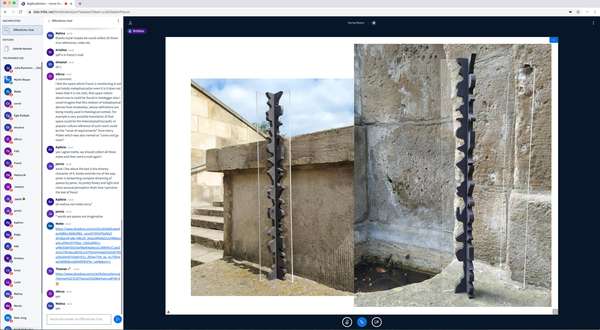

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

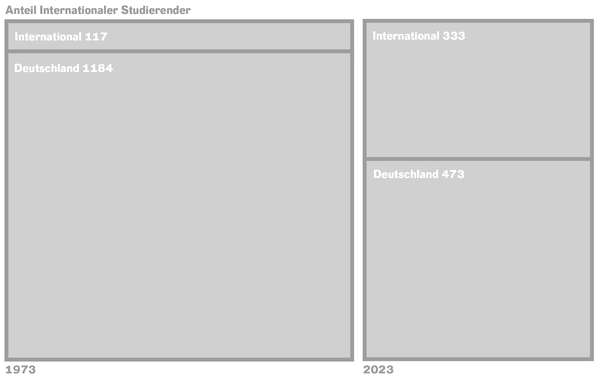

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

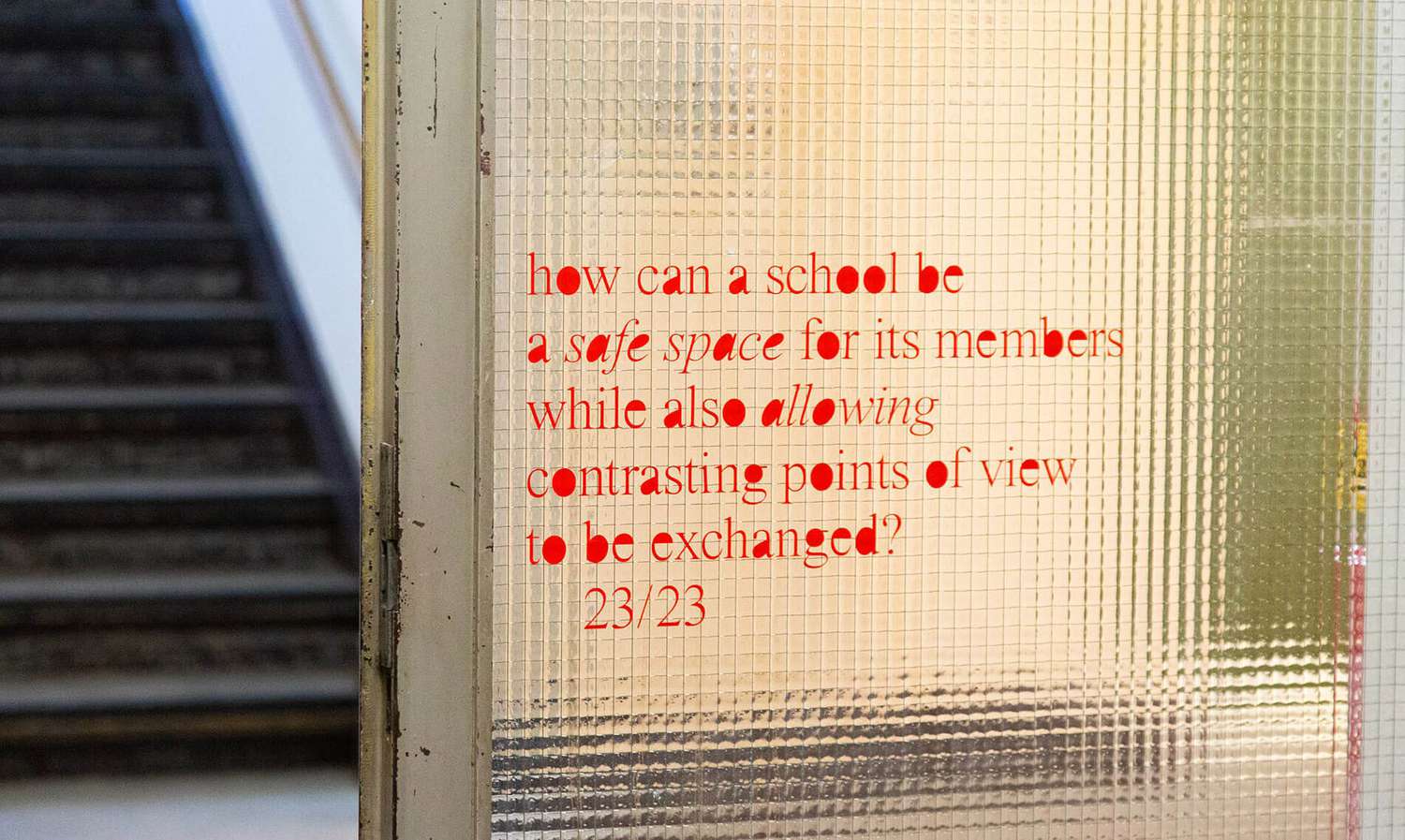

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

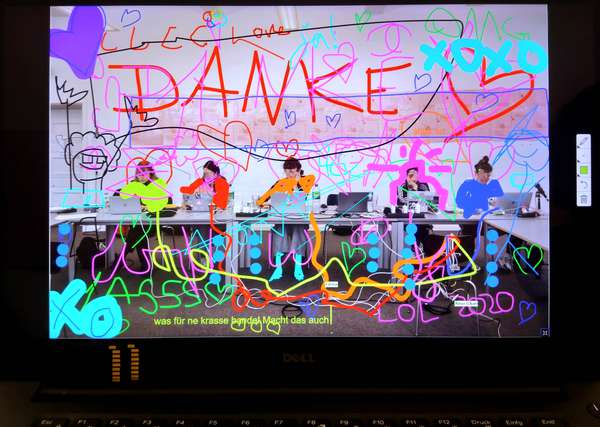

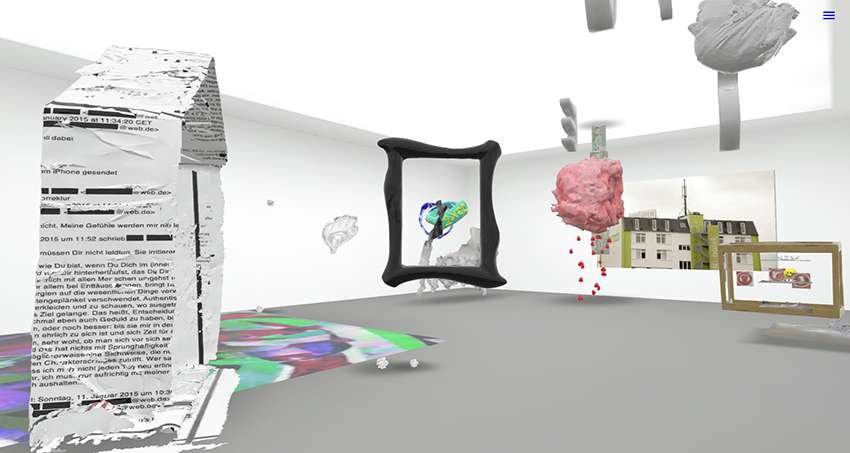

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

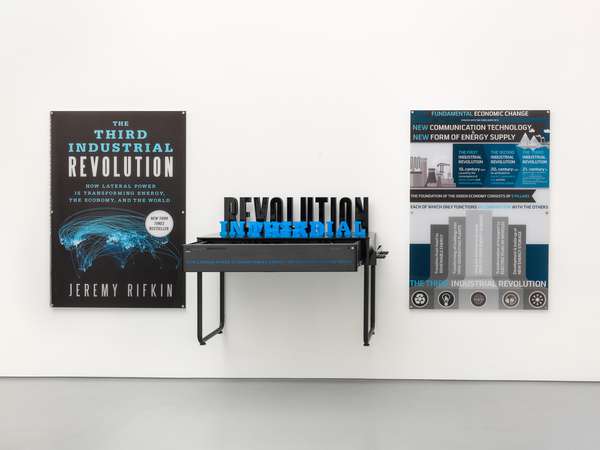

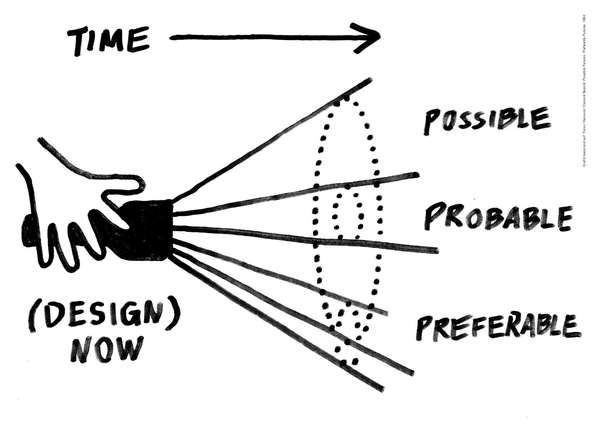

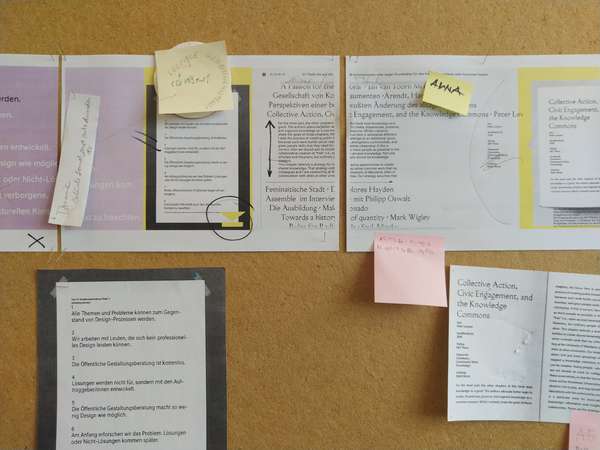

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?