Lingua Franca as a Communication Transit Point

Based on the language policy of his home country Kenya, Nicholas Odhiambo Mboya takes a look at the language dynamics in Germany, at the HFBK Hamburg and proposes a compromise language to reconcile local and international needs.

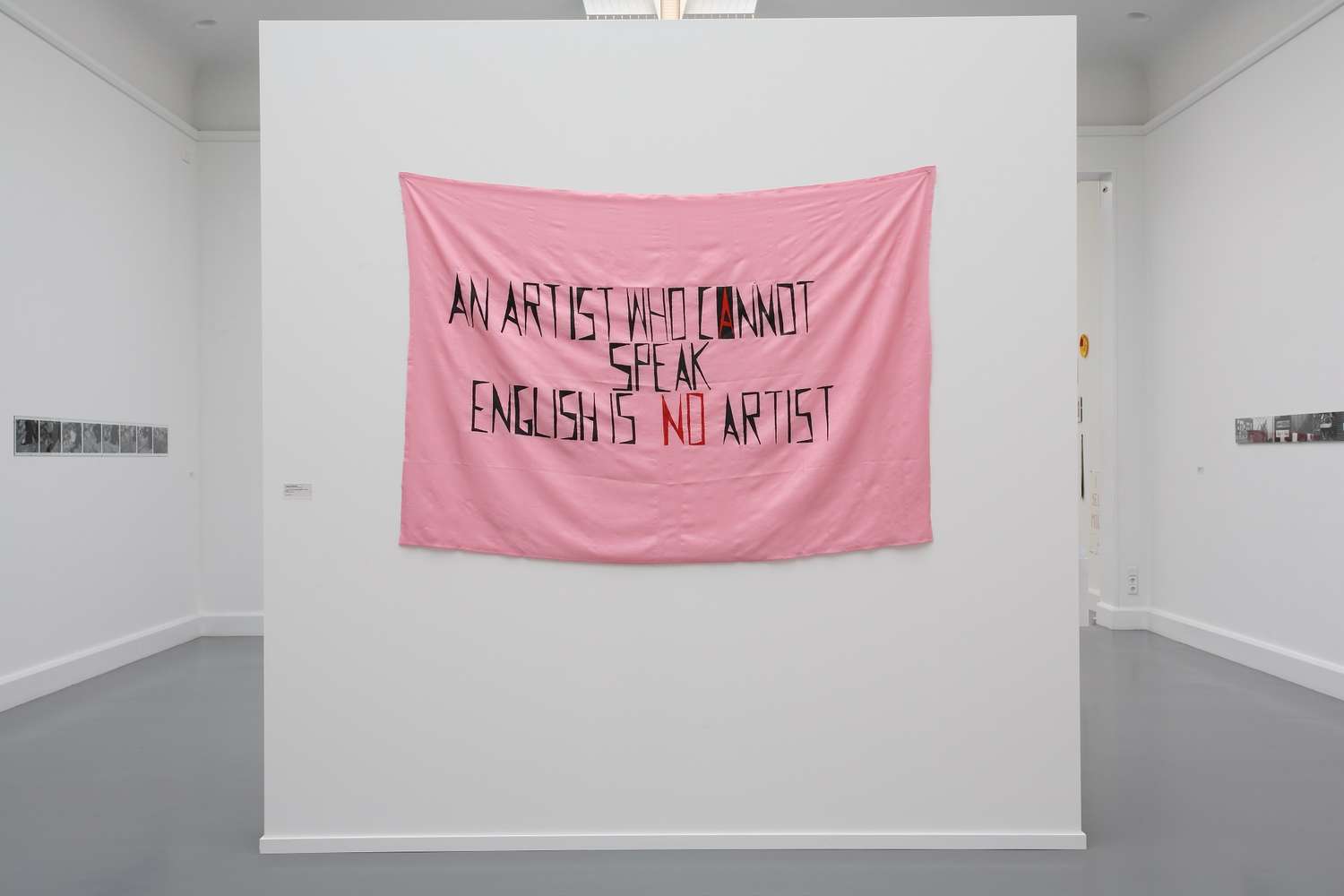

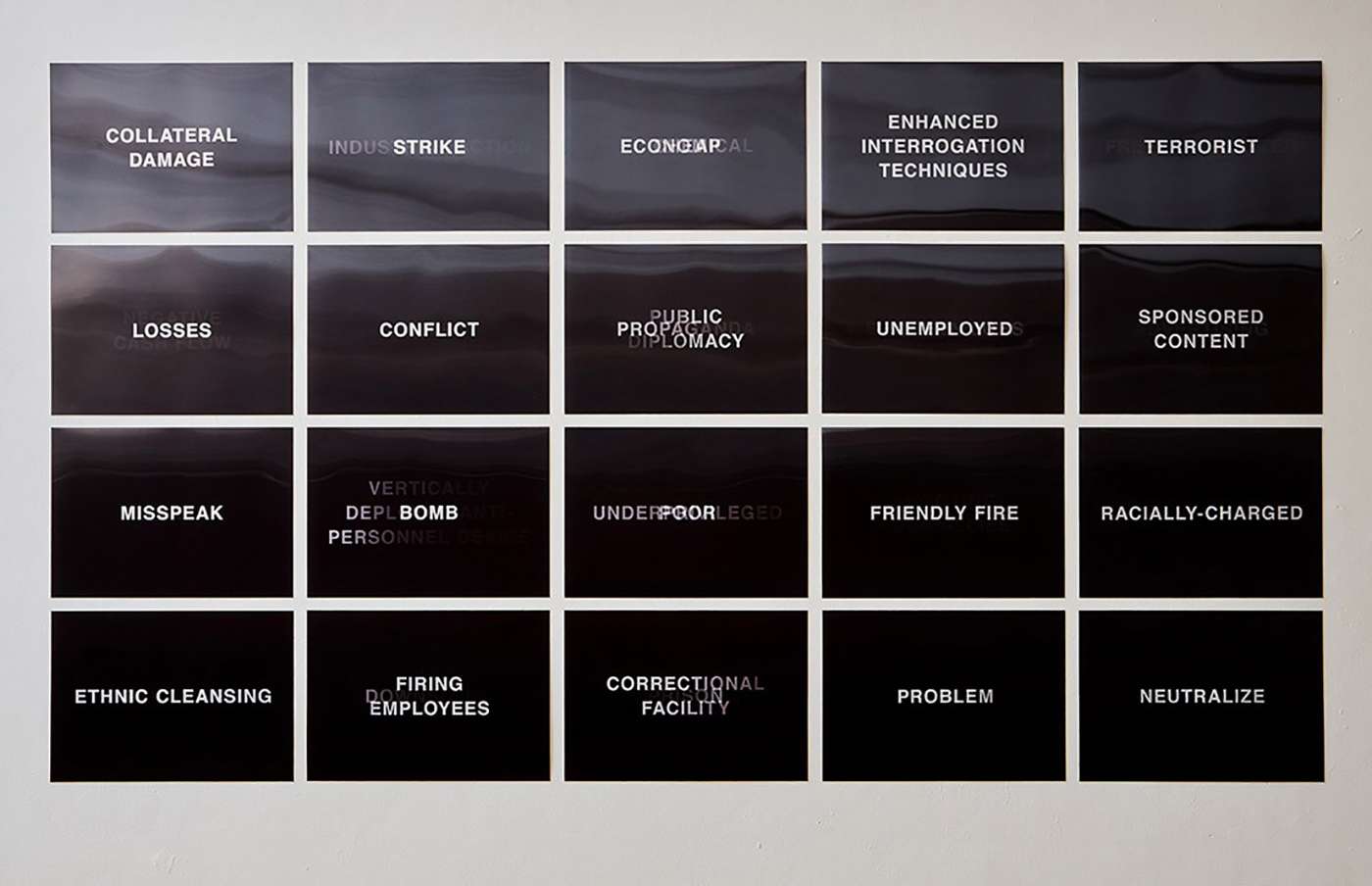

The language we speak influences the way we perceive our surroundings – and the way our surroundings perceive us. This is especially true if you live in a country where the lingua franca is foreign to you. Not being fluent in the national language of your place of residency is usually a tricky business. From misunderstandings to exclusion from the job market and experiences of bureaucratic burdens: Not being able to communicate in the lingua franca can be linked to many forms of discrimination, which reveals the close connection between language and power. This raises questions about how international students experience language politics, specifically when migrating from the Global South to the Global North. It extends to discrimination for not being competent enough in the national language and the contradictions observed through surprising gestures by native speakers when the migrant is well-conversant with the language.

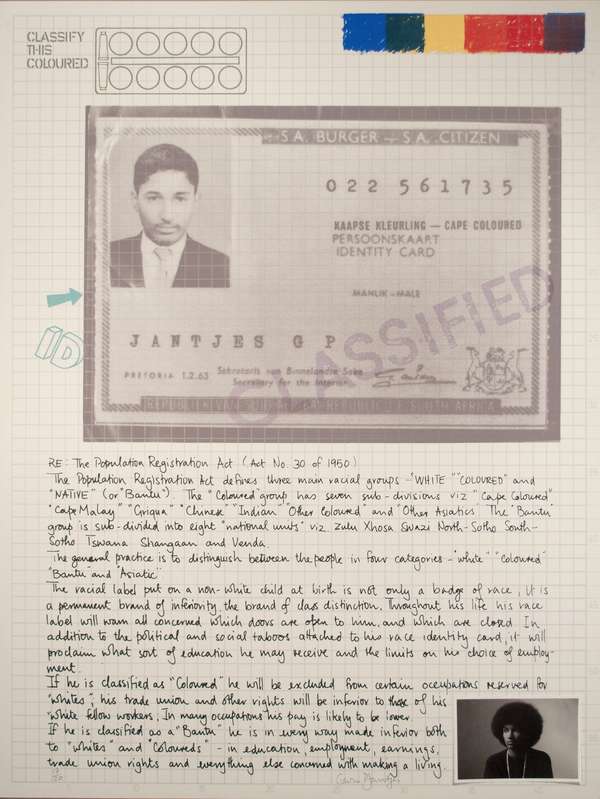

Language choice (including language shift) is usually heavily influenced by political and economic factors, and not by sentimental ones. The official language becomes a vehicle for political participation and socio-economic drive.[1] The rules in speaking and writing as well as those governed by administrative policies, mitigate bilingual inevitability due to other existing languages and linguistic hierarchies within a given space to foster lingual cohesion and discordance of societal engagement. Therefore, countries with a background in colonial prowess understand the depths of language execution that can be seen through stringent language policies within those countries. Broader communication and international accessibility are ambiguously unique depending on the geographical location, institutions, and the authorities at play. One of the most effective means of nurturing a language is by using and sharing it. However, each system code is influenced by local conditions and the desire to construct identities that reflect the dynamic lifestyles of its members. For example, languages in Kenya are heavily influenced by each other, which led to the development of Sheng, a code-switching language that constitutes itself out of different local languages: It is primarily a mix of Kiswahili and English embedding other local languages.

In the Kenyan context, language has seen a fluctuation process since the colonial inception depending towards which side the wave of interest sways. In her 2009 article, Clara Momanyi, a Professor of Kiswahili literature, claims that the decision of Kenya to use Kiswahili as the national language immediately after independence came as a need to foster human development. This is because Kiswahili is the language of interethnic communication in Kenya, where it bridges the linguistic gap between communities. Kiswahili has the oldest uninterrupted history as an African written language compared to other African languages used in the country. Its written literary history spans almost three centuries. It therefore has a significant role to play in higher education for the purposes of equipping trainees and future professionals with the communicative skills needed to foster national development.[2] Some scholars, however, suggest that Kiswahili's development into an international language in the 19th century was due to trade, wars, colonial administration policies, and the linguistic advantage of being related to Bantu languages on the continent of Africa. Among the most significant factors, Christian missionaries (bible-wielding diplomats as Ngugi Wa Thiong’o refers to them) played a key role in promoting Kiswahili development, using Kiswahili as a means of preaching and teaching, as well as conducting lexicographical research in the dialects of Kiswahili that led to dictionary compilations. This contributed greatly to the spread of Kiswahili in the interior.

Nevertheless, the linguist Wendo Nabea states that the denial of African's right to study English at the time prompted them to learn it due to their curiosity about “modern elitism.” The colonized subjects realized that learning the English language was a sure ticket to wealth and white-collar jobs, so denying them a chance to do so was a way of condemning them to menial jobs forever. Thus, the Kikuyus of Kenya established independent schools so they could learn English without impediments. It is undeniable that colonial language policy was eclectic depending on colonizers' interests. The Phelps Stokes Commission of 1924 is a good example. In the report, the commission recommended eliminating Kiswahili from school curriculums, except in areas where it is spoken as the first language. Further, the commission suggested that early primary classes should teach the mother tongue, and upper primary to university should teach English. This indicates that the colonial language policy in Kenya during colonial rule was never compact. Its position on the teaching of English and African languages was mainly ambivalent. One might presume the incomplete nature of having a local lingua franca at the time was the British colonialists’ well known “divide and conquer” measure to prevent nationalism that would later cause mayhem to the colonial regime.[3]

However, out of this phenomenon Kenyans developed a very integral, playful approach to mixing different languages is something that seems to be seen much more ambiguously in Germany. Although you find many people with a migration background here, which obviously influences the language dynamics, there is a major discourse (like in the UK and France) about “protecting” the national language from foreign influences (which is absurd when you consider that languages have been interacting with each other from time immemorial; certain terms such as “restaurant” for example have a French background but are commonly used in Germany). This can also be felt in issuing residency permits. For a long time, such permits were associated with strict language barriers. It was not until recently that this started to change: The federal authority as per the latest update of the National Visa modification of sections §§ 30, 32 AufenthG (German Residence Act) – regarding the requirement of German language skills for family reunion with professionals and specialists – came into force on December 31, 2022. The immigration rules regarding proof of German language proficiency up to A2 level for persons applying for this type of visa are no longer valid; simple German language skills based on a recognized A1 language certificate “may’’ be mandatory (German mission in India 2023). One might assert this as Germany’s humanitarian responsibility and an outlet to combat the influx of labor force in the country. Such an amendment, I believe, reveals the demographic shortage and generational imbalance that pose problems to economic productivity.

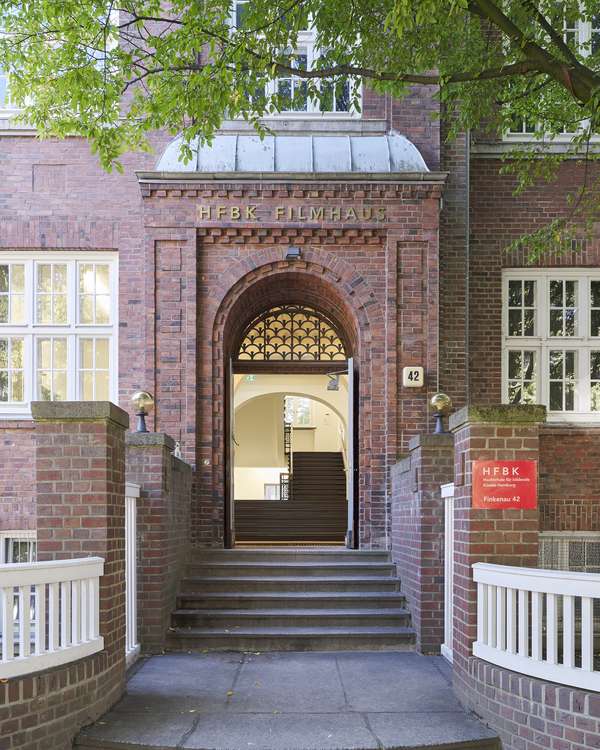

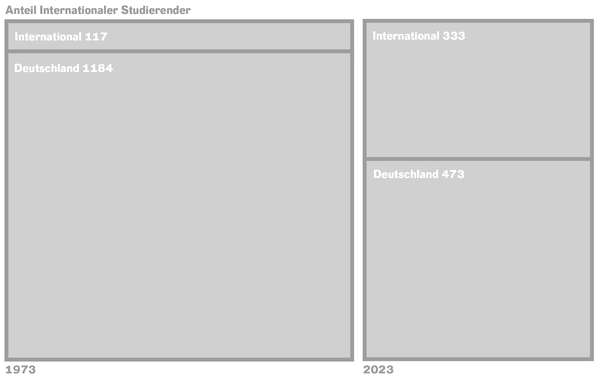

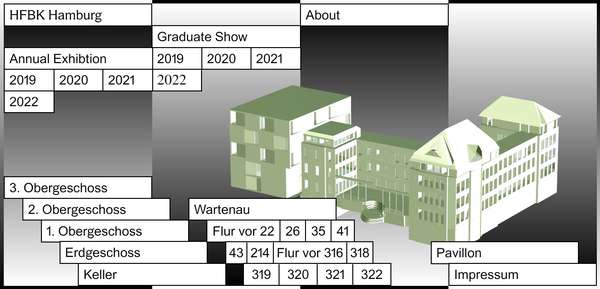

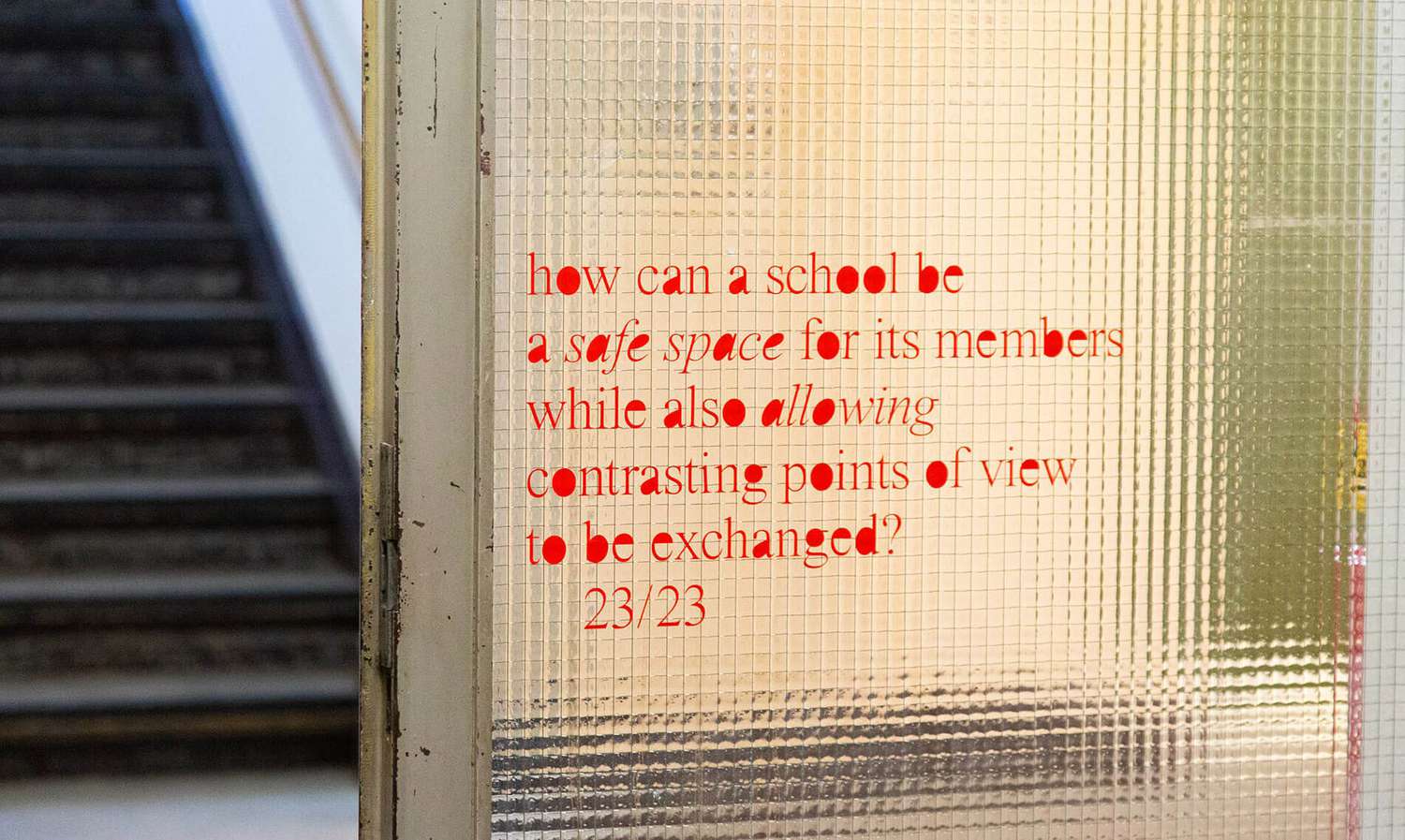

At German universities, foreign students are required to show proof of German language proficiency. The HFBK Hamburg requires applicants for Bachelor's degree programs to show German proficiency or evidence of ongoing language training, whereas Master's program applicants do not need to provide proof of language proficiency. This creates a discrepancy pertaining to students and raises questions about the hierarchy of degree programs and the exceptions and exemptions that accompany them. However, there is almost no language barrier between the staff and the students. This is because foreign students who don't speak German are obviously well-versed in English. It is expected for those who do not speak English to have a sufficient, proficient, or advanced command of German at levels B1, B2, or C1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages.

Consequently, students can communicate with staff in either language. In some cases, however, professors or staff administrators may not be native English or German language speakers, and this also applies to students. Disparities like these influence students' choice of lectures and seminars. A holographic barrier occurs when both speakers are encouraged to learn the "other" language to fill the linguistic communication void so that there can be a cohesion of understanding. As an example, some German and foreign students who already have a good grasp of the German language are taking online English courses to catch up with other English speakers in order to better apply to the international community, the same applies to English speakers with the intention to permanently reside in Germany. Consequently, we can ask: What does the concept of internationality mean when it comes to language attainability, particularly at international universities in Europe? According to American linguist Carol Myers Scotton, what makes an alien official language attractive is the reasoning that all groups (in theory) start at zero in acquiring it.[4] Therefore, should all German native staff members in international institutions within German-speaking territories also prove a command of the English language at an advanced level as a job application requirement?

On my first day at HFBK Hamburg, the international office organized an introductory meeting and assigned classes for foreign Bachelor’s students. To my surprise, native German speakers addressed international students in advanced German without asking about their preferred language. Only in the assigned class did the professor inquire about the students' preferred language and switch between English and German as needed. After all, internationality is a transnational discourse with the aim of satisfying the individual interests of diverse parties. Due to these bipartisan backgrounds, language becomes absolute. The double-edged sword of compromise is still a power struggle at the national level. Perhaps the “Germlish” codeswitch might be the ideal lingua franca for connecting local and international residents in Germany, similar to Sheng' in Kenya.

Nicholas Odhiambo Mboya graduated in 2023 with a Bachelor of fine Arts in the class of Prof. Angela Bulloch.

Notes

[1]Carol Myers Scotton. Social Motivations for Codeswitching. Evidence from Africa. Oxford University Press, 1995, p. 28.

[2] Clara Momanyi. “The Effects of 'Sheng' in the Teaching of Kiswahili in Kenyan Schools." Journal of Pan African Studies, Vol.2, No 8., 2009: 127-138, p. 124

[3] Wendo Nabea. "Publication/ Language policy in Kenya: Negotiation with Hegemony." The Journal of Pan African Studies, Vol 3, No 1, 2009: 121-138, p. 124.

[4] See footnote 1, p. 28

This article appeared in Lerchenfeld issue #67.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Long days, lots to do

Long days, lots to do

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

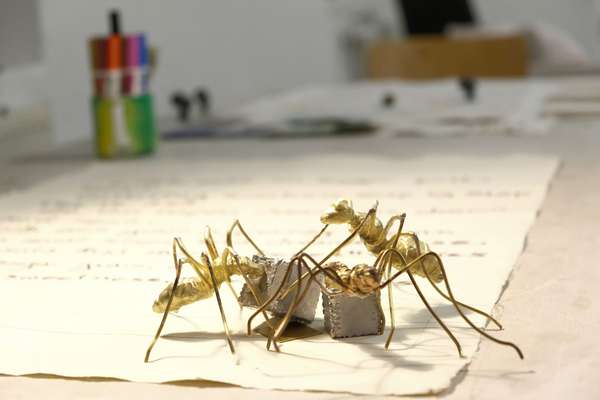

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

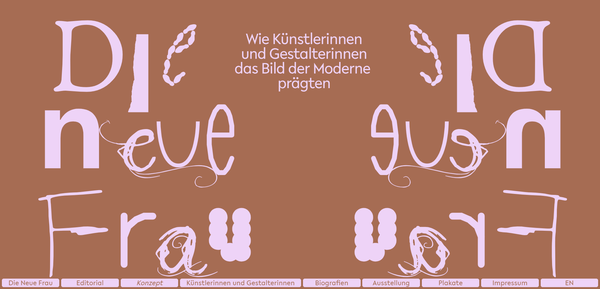

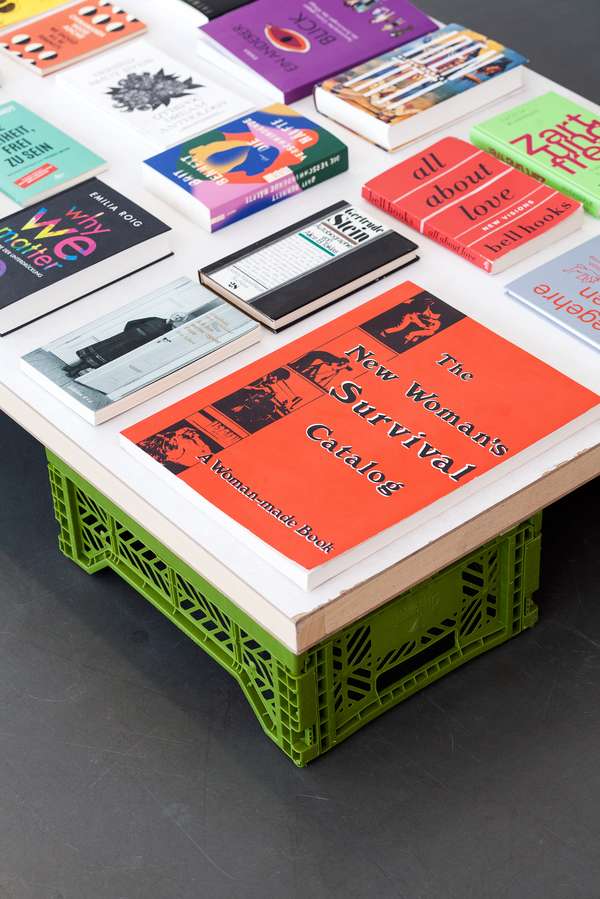

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

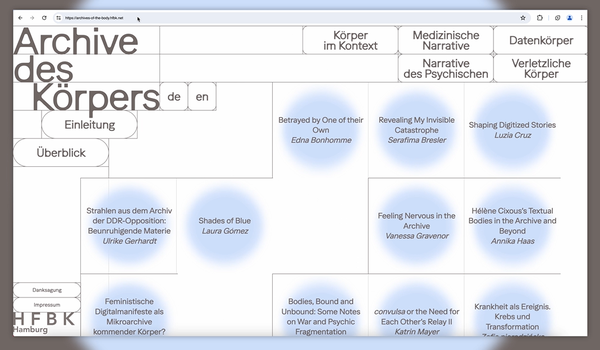

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

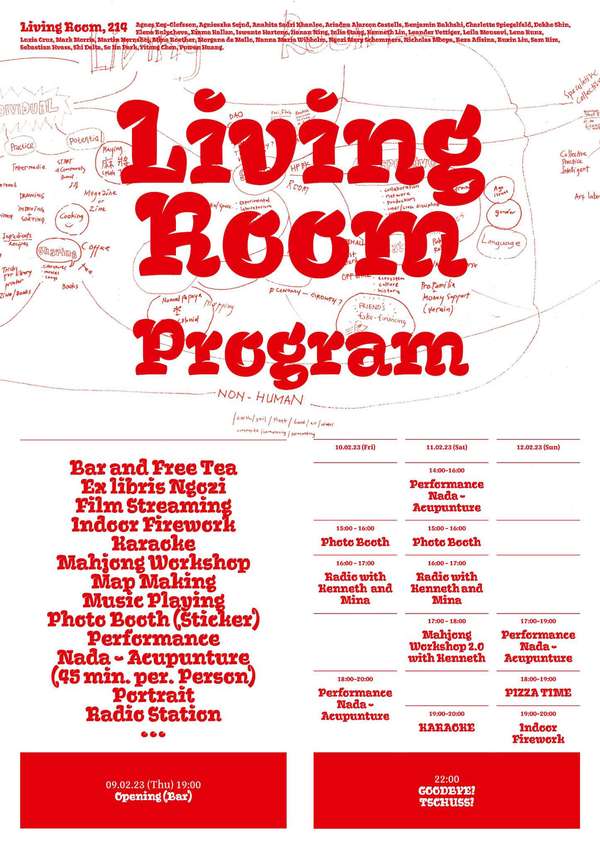

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

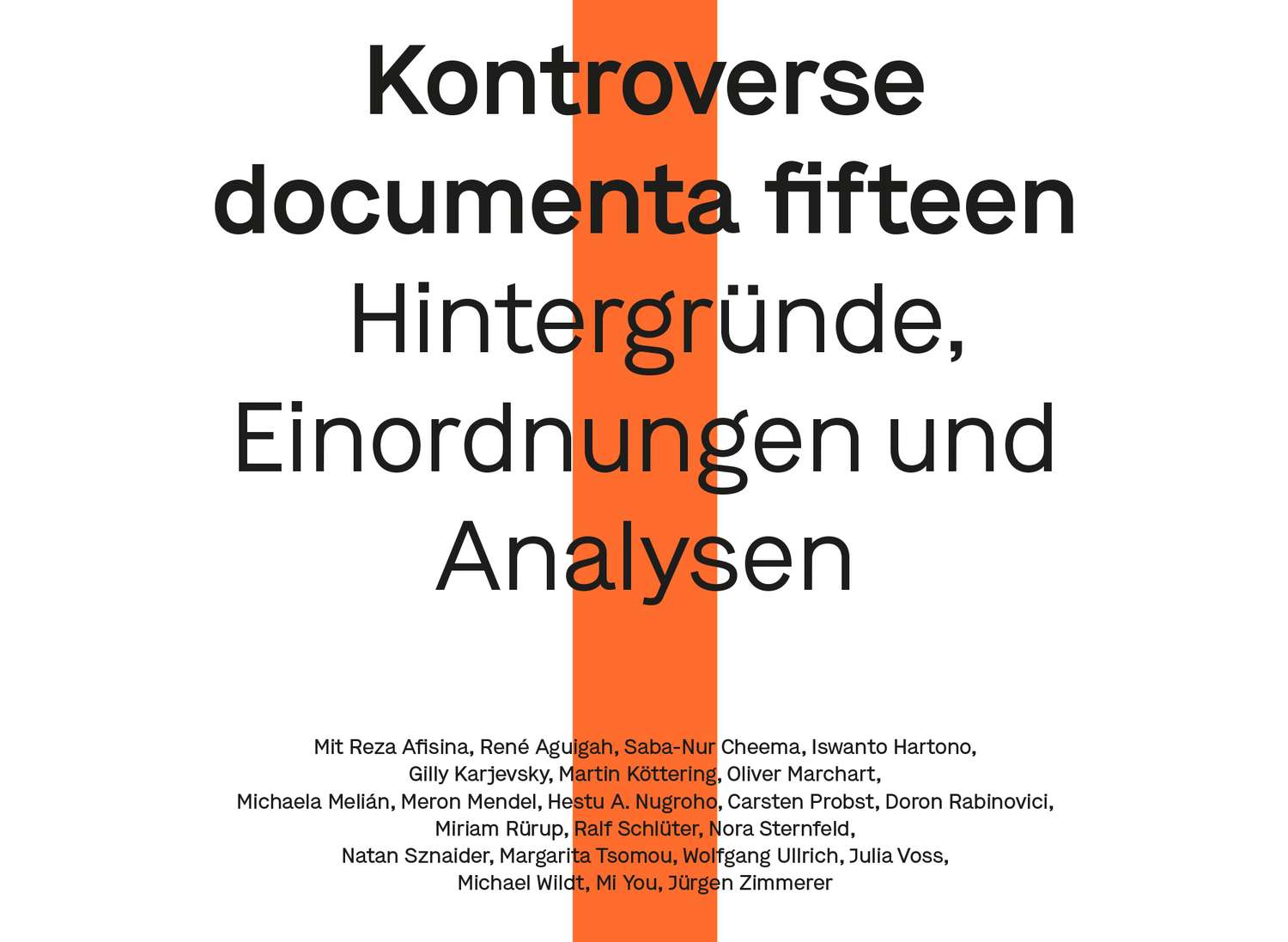

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

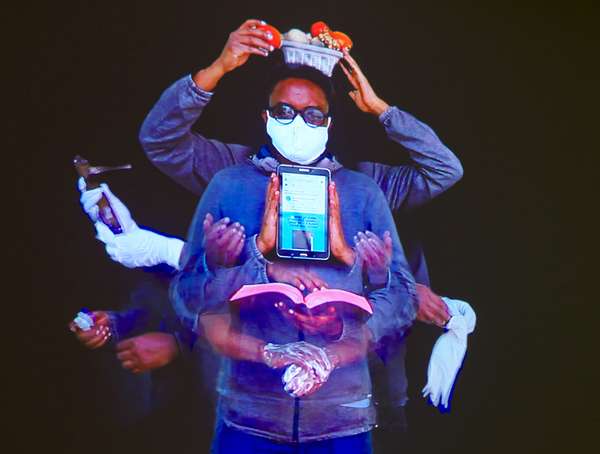

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

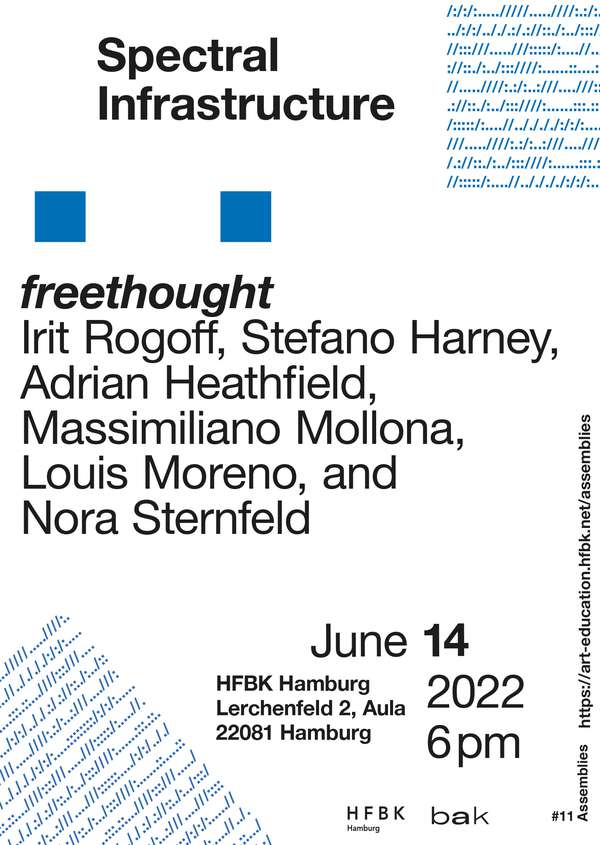

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

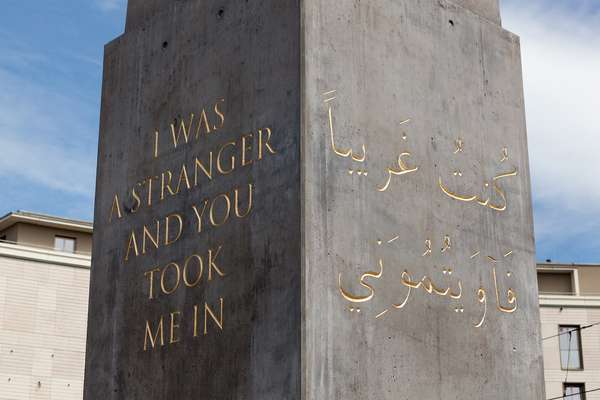

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

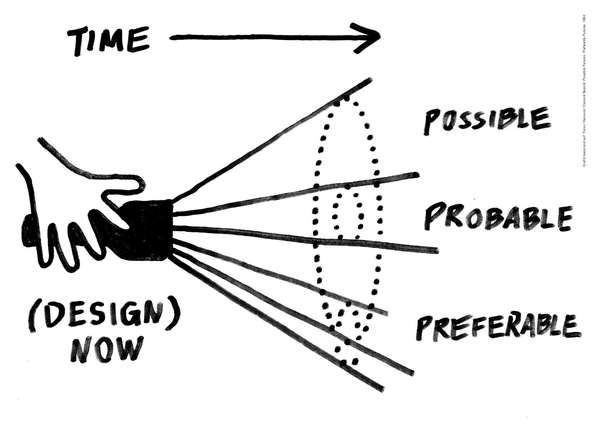

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?