Artists Who Risk Their Lives

Since 2013, the non-profit organization Artist at Risk has made it its mission to support persecuted artists and cultural producers, facilitating their safe passage from their countries of origin. They have assisted numerous persecuted and imprisoned artists. Lerchenfeld spoke to the two founders and directors Marita Muukkonen and Ivor Stodolsky.

Lerchenfeld: What was your motivation for founding Artist at Risk (AR) in 2013? Was there a key moment, a special event that moved you to found the organization?

Ivor Stodolsky: Between 2011 and 2013 we were curating the Re-Aligned project, which presented rebellious and revolutionary movements by artists from around the world. We presented artists who were part of the Egyptian revolution, who were involved in Occupy Wall Street in New York, or in protests in Spain. In 2013 we were just doing our work with programs that involved residencies from different countries when we realized that there is no way that some of these artists can go back. That really was a turning point for us. That is why we have developed a program that offers artists a safe haven.

Marita Muukkonen: At that time, we had no knowledge about a program that was mainly focusing on professional artists or people working in the art field. There are programs for journalists and authors that have a long history and are well established. But in 2013 there was no organization or program that was dedicated to visual artists who had to leave their country. It was and is important to us that they can come as artists, not as refugees or asylum seekers. We want them to work in their professional context, where they can come into contact with colleagues and audiences. They have residencies at museums or other art institutions. We are working with high-profile artists who are risking their lives. They have to be treated accordingly. And this is our driving force. It’s a privilege to work with them.

IS: They are human rights activists, not only artists. Even though they express themselves through the media of art, they do a lot for their local communities and not just for themselves or for the sake of being a controversial artist. They don’t want to be famous artists, but they are becoming known around the world for their incredibly important work, their courage. They are productive, incredibly talented people.

Lf.: How does the application process work? How does someone apply for an Artist at Risk residency?

MM: Artists can apply through our website. First, they do a risk assessment, because we have to evaluate if the risk is real. And of course, there are artists who are more at risk than others and fear they will be murdered or tortured. Then we verify that they are professional artists, and then we have to find the right institution for them. If they are coming with a family, we have to look for an institution that can host a family. We also look at their language skills. Many come to the EU, but sometimes it is also possible to bring the artist to a partner institution in a neighboring country that is safe. There are many factors we have to consider. And of course, the biggest problem for artists entering the EU is getting a visa. A lot of our energy goes toward starting the visa process.

Lf.: How big is your team to organize all that? How many people are working with you?

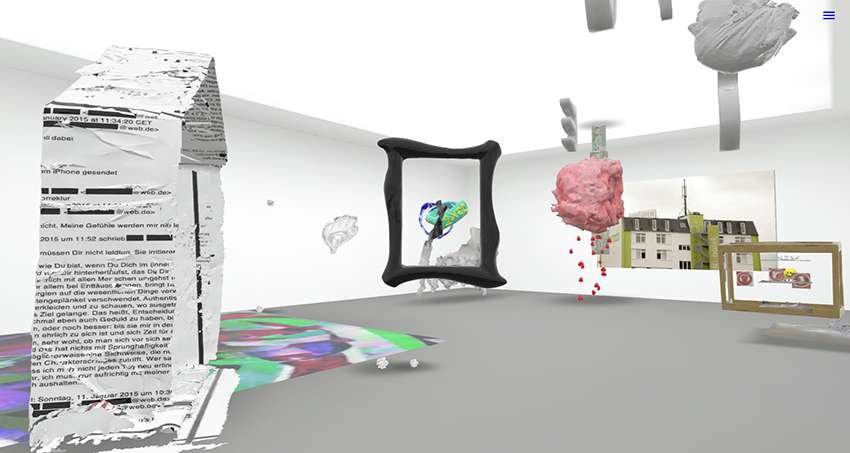

IS: We have an office in Helsinki and one in Berlin. The people at AR mostly work online. And we have a broad network of solidarity teams who match the applicants with the right host institution. They find out everything about the needs and requirements of the artists as well es the institutions. We have set up the solidarity teams according to different regions. Currently there are solidarity teams that take care of applicants from Ukraine, Russia, Belarus, Afghanistan, and the Arabic-speaking world. But in addition to the AR offices and the solidarity teams, there are of course also numerous employees at the partner institutions who are involved in the process: residency coordinators, people who curate shows and organize the production of works, cleaners, and many more.

MM: At the moment we have a massive number of applications from Afghanistan, Ukraine, and Russia. There are 450 artists at risk in Afghanistan. We have 1,000 applicants from Ukraine, and many Russian dissidents are also applying. But we cannot forget the rest of the world. We are looking for more host organizations, especially in Germany. To this end, we recently started a new partnership with the Goethe Institut. Institutions that are interested and have the ability to host artists at risk can apply via our website. So if there are institutions also in Hamburg that are considering joining our network, it would be great if they would apply.

Lf.: What are the special requirements for institutions to become a host institution?

IS: We need to screen the institutions to make sure that they meet certain minimum standards. They have to show us the accommodations they provide. But they also have to represent certain ethical values and principles.

MM: Currently we are witnessing great solidarity in hosting Ukrainian artists. Many institutions are accepting Ukrainian artists and cultural producers. We hope that they will remain with us in the network over the long term and that they will also accept artists from other countries in the future.

Lf.: Is the resistant role of artists in current conflicts or wars in their home countries still romanticized too much by the Western art scene? Is the image of the struggling artist changing?

MM: There is nothing romantic about hiding in a basement or safe house. You can’t practice your art, you can’t work in a situation like that. If you are a musician, a painter, or a filmmaker, basically you can’t work. People are risking their lives, they are being tortured, executed. They can no longer be artists. They are targeted as a social group, and it really feels criminal that they are left behind, as is the case in Afghanistan right now. The EU and Western countries have not done enough to help these people. As we are speaking, we still hope that the German government will offer visas for art producers at risk.

IS: I think the image of persecuted artists has changed a lot. Maybe in the past, during the Cold War, there was a romantic image of the repressed writer living underground and writing against the regime. Today, however, the situation for endangered artists is quite different. They are no longer respected for their work. People want to get rid of them, to silence them. The reality that people live in is very different to former times. Many persecuted artists today also no longer come from the “classical” disciplines. They are visual artists, performance artists, or popular musicians who are no longer allowed to perform in their home countries. An example is the Somali musician Lil Baliil. He has been targeted by militant groups who view his music as a threat to Somali culture. Following death threats, he is currently an Artists at Risk resident in Berlin. It may well be that there is a tendency in the West to romanticize the image of the persecuted artist. But perhaps to take something positive away from this: sometimes it takes a little “glamor” to shed more light on artists who otherwise remain invisible. But when you look at the people risking their lives and what they tell us about it, it is not glamorous at all. For example, if you read the prison diary of Pussy Riot member Maria Alyokhina, it’s horrifying what she went through. There is nothing glamorous about it. It’s shocking reality.

MM: And there is another aspect that we should not forget. If you have worked as a political artist and had to leave your country, then life in another place is safe and you are protected, but at the same time you can no longer intervene with your art in the familiar environment. This is also difficult for many artists.

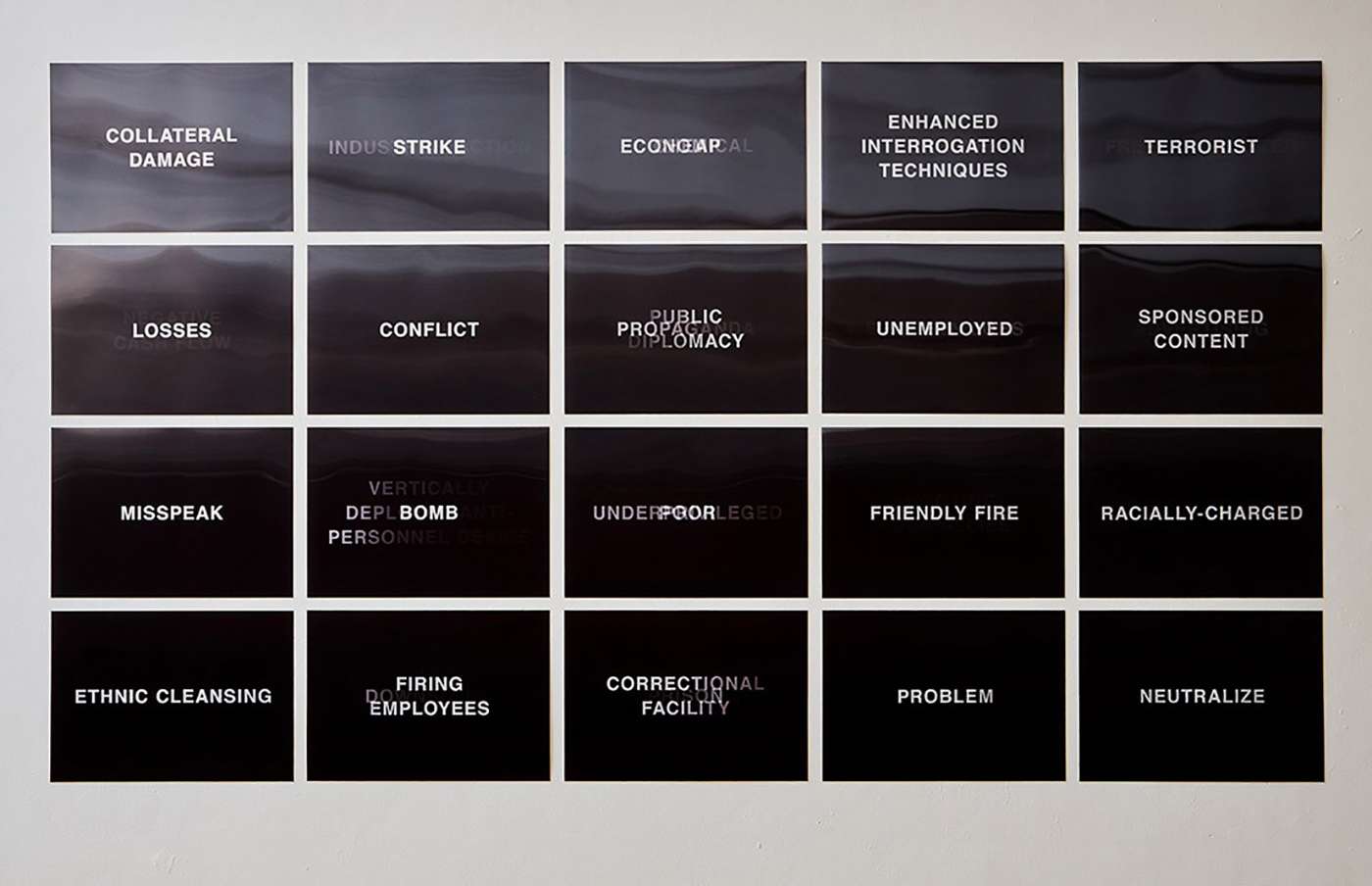

Lf.: You use very specific terms on your website and in your interviews and avoid others. For example, you don’t use terms like “refugee artist.” How important is language to you in this context?

IS: We want to treat the artists as artists, and not label them as “refugee artists,” because a certain idea is also conveyed through language. We do not want Syrian curators living in Berlin to be “allowed” to present only Syrian artists. There are these expectations, and we want to consciously undermine them. We use the French terms like “Immigré Artist” or “Exilé Artist“.

Lf.: In mid-February, together with the ZKM Karlsruhe, you organized the online conference “Institutions and Resistance: Alliances for Art at Risk”, where numerous artists at risk as well as theoreticians and partner institutions spoke. Two weeks later, Russia’s war against Ukraine began. What has changed for you and your work since then?

MM: We could not foresee then what would happen a few days later in Ukraine. Currently, there is a great sense of solidarity. The alliances are growing. We very much hope that these ties will continue beyond this, because we face many other crises. We need strong institutional power to bring about political change—for example, on the issue of humanitarian visas.

VS: The cooperation and alliances are growing. There are new networks in Sweden, Spain, and northern Italy. And we are working with the Goethe-Institut, as we mentioned earlier. Something like a pan-European network is forming. And for the first time in its history, UNESCO is funding projects by and with living people, and not just protecting stone cultural assets or monuments.

Lf.: What would you like EU policymakers to do? How could they make your work easier?

IS: That is easy to answer: humanitarian visas at the European level would help. These are visas that could be issued on humanitarian grounds by a national embassy abroad. They allow third-country nationals to apply for entry into the Schengen area on humanitarian reasons. If we let the Ukrainian people stay and work in the EU for a year or two, it would be great if this could also be possible for other people—for example, from Afghanistan. It is shocking to see how comparatively few people from Afghanistan are currently turning to the EU in search of help, and yet finding no admission. The same goes for other crisis regions. We must not forget that when we help people, especially artists in need, they not only enrich our lives and our culture. They also go back to their home countries strengthened and support their local societies.

This text was published first in Lerchenfeld #62. The online conversation was conducted by Beate Anspach on June 13, 2022.

For more information: https://artistsatrisk.org/

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Long days, lots to do

Long days, lots to do

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

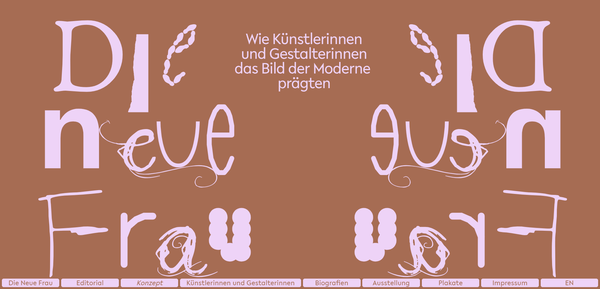

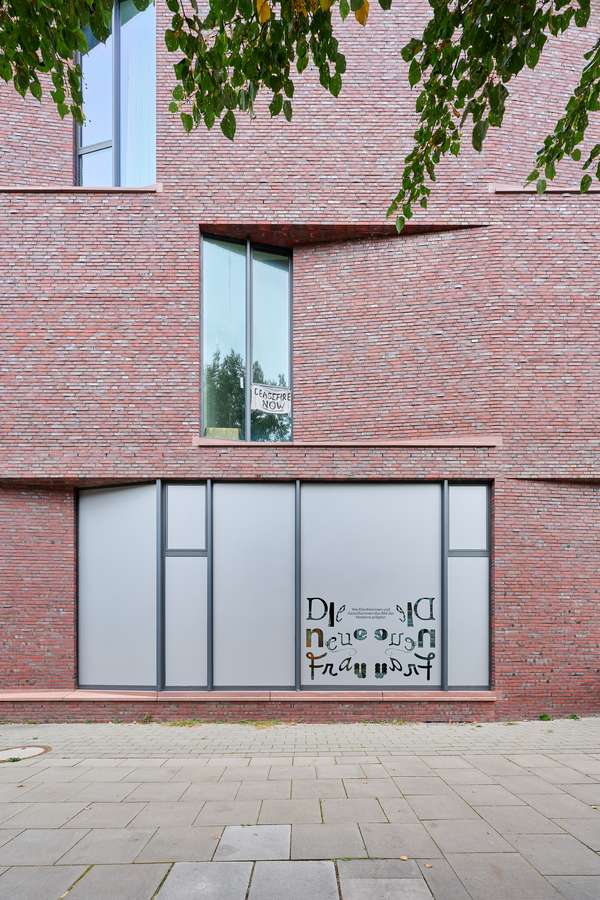

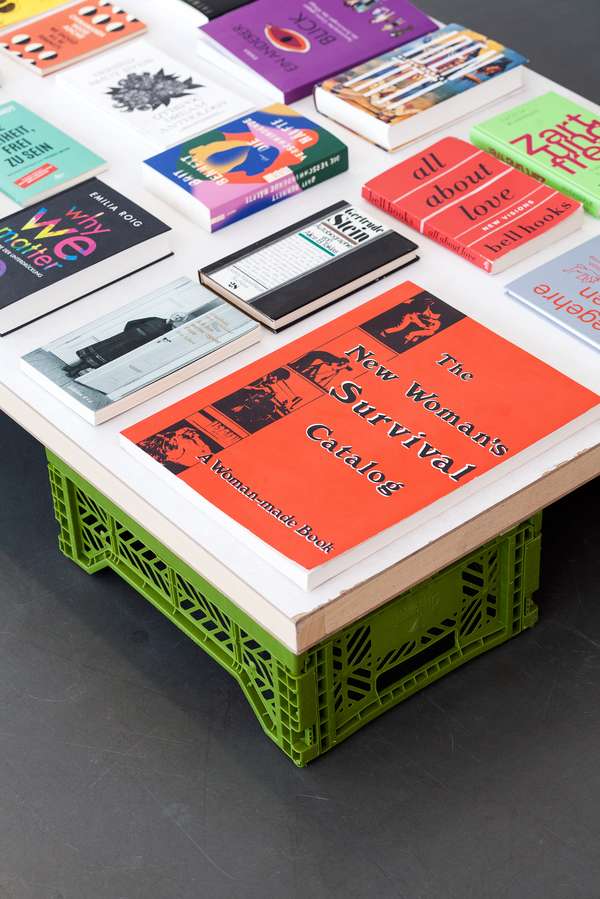

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

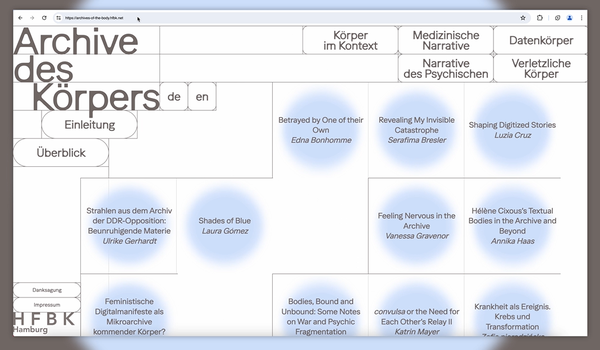

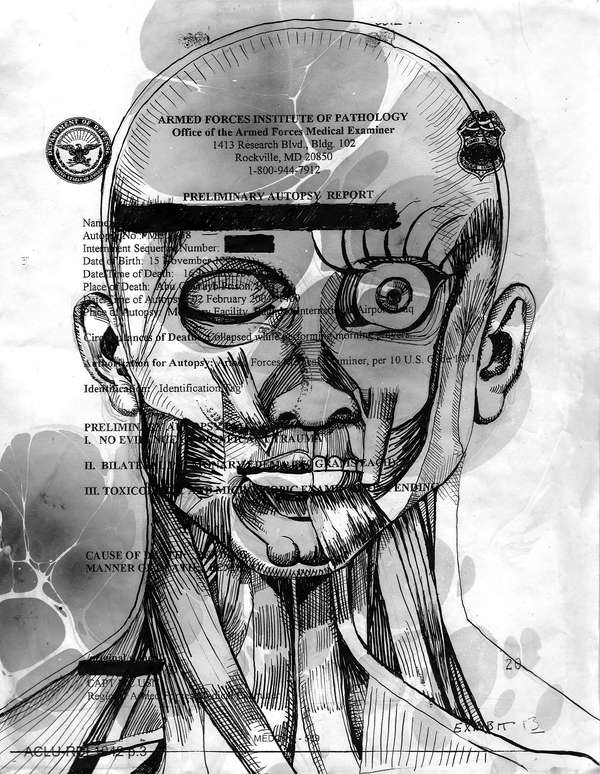

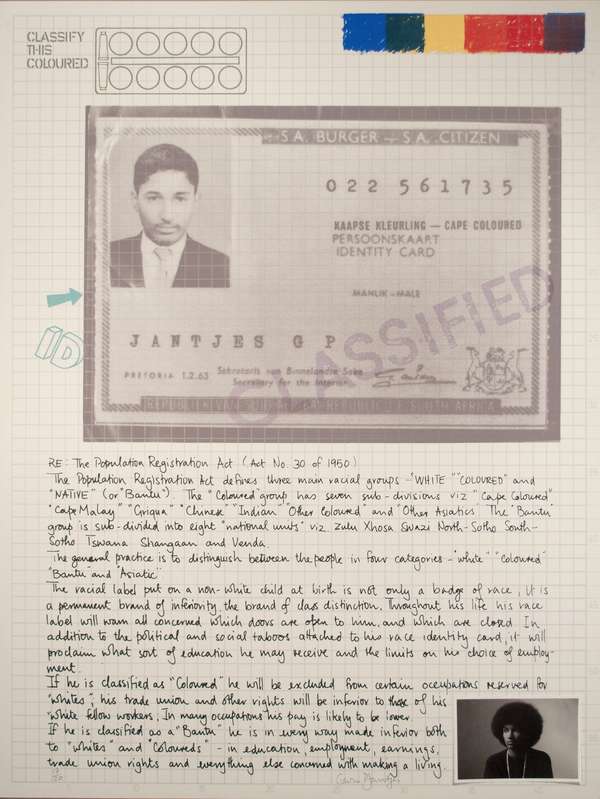

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

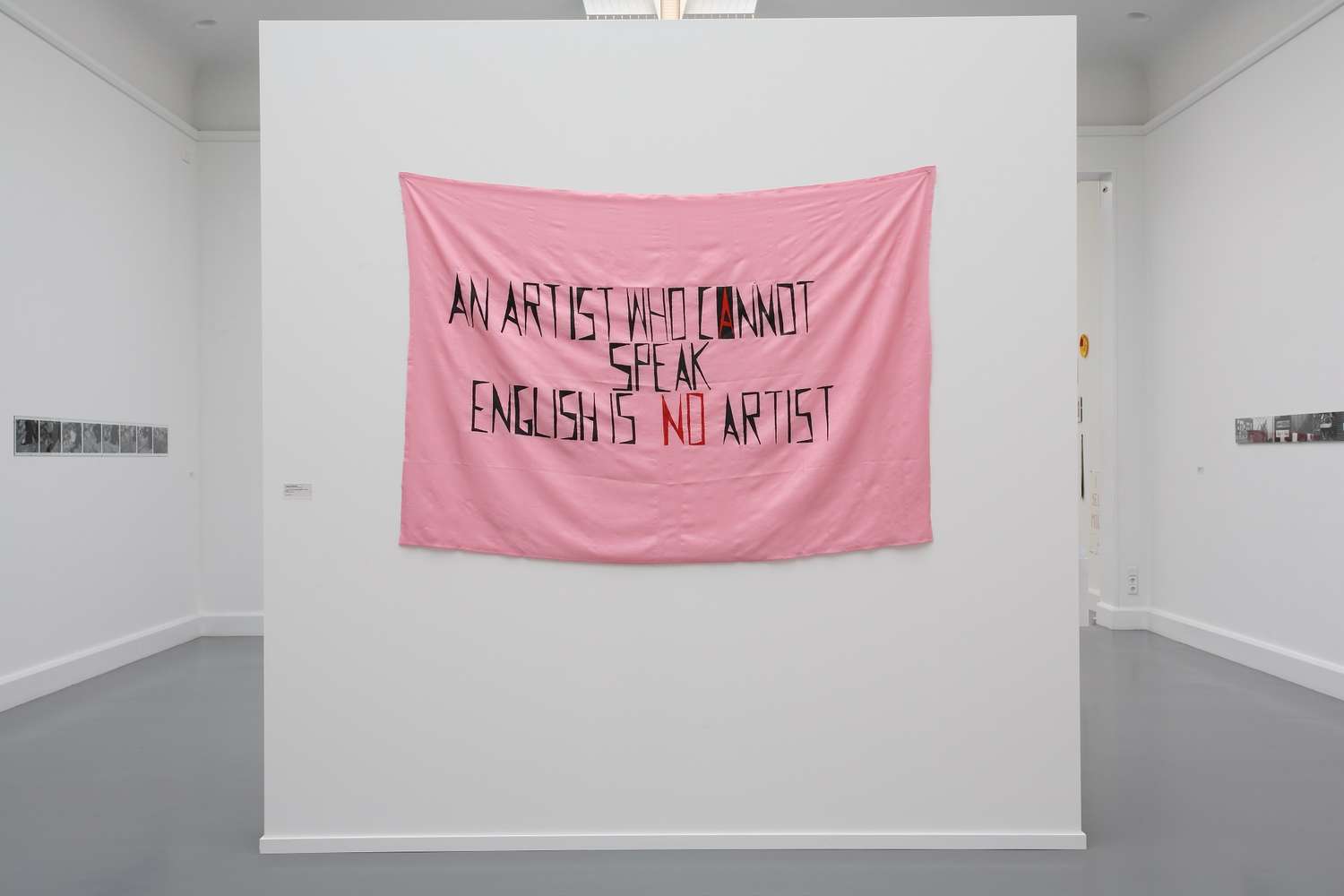

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

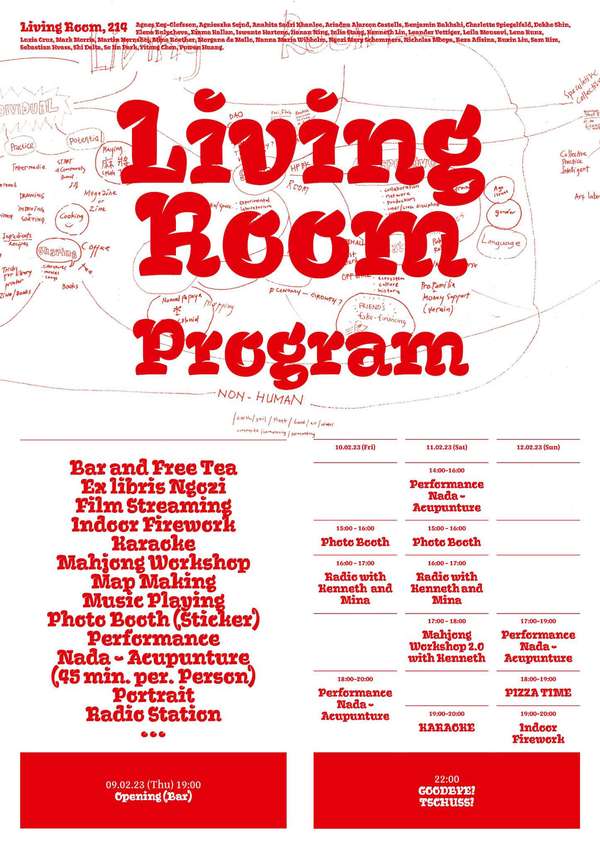

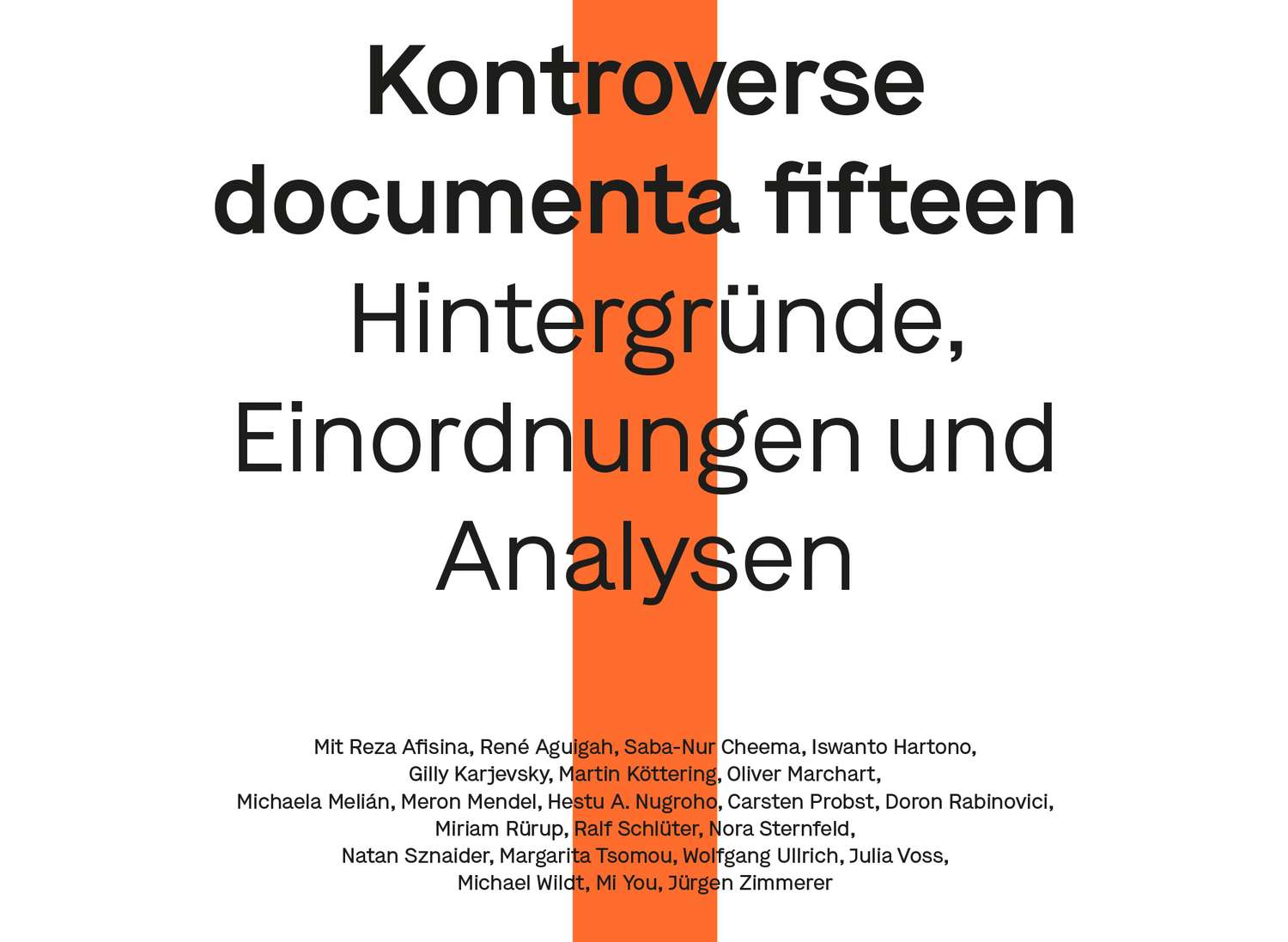

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

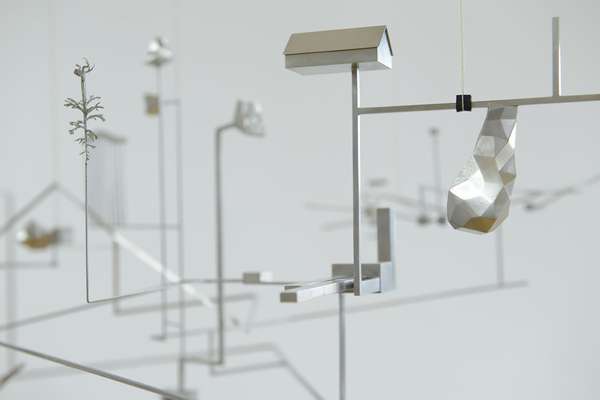

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

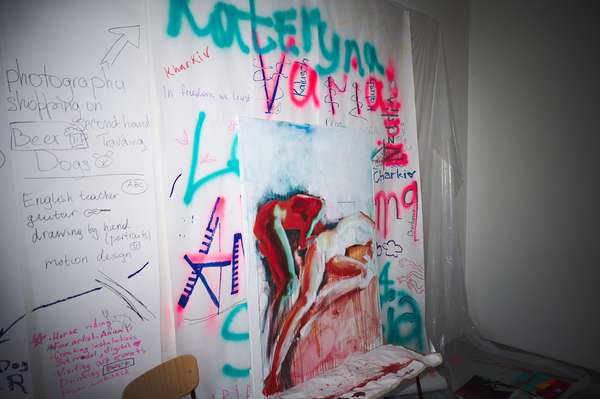

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

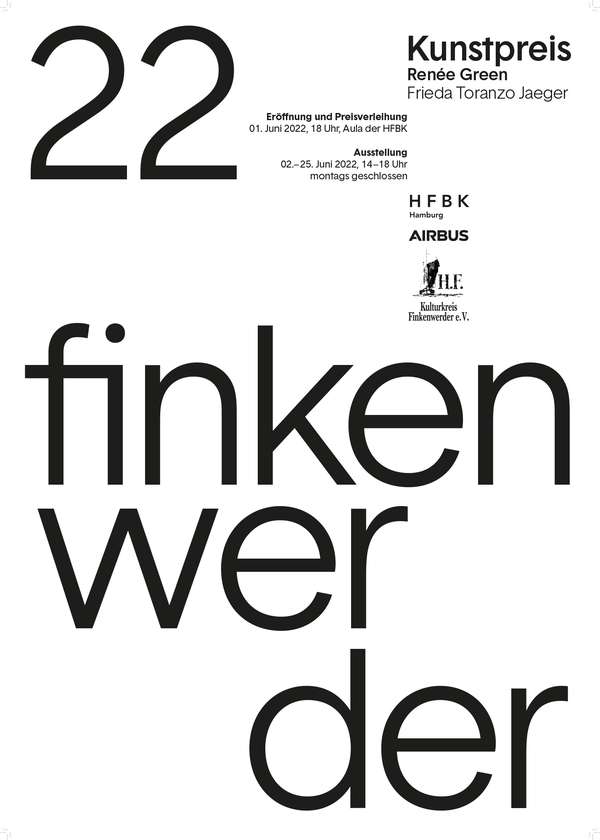

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

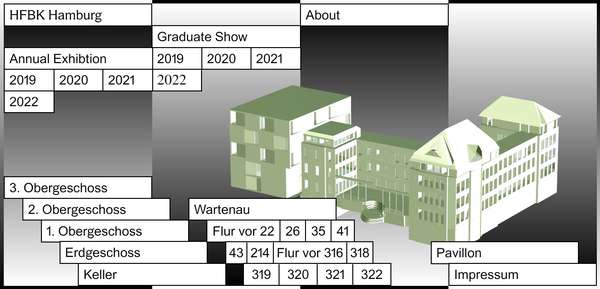

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

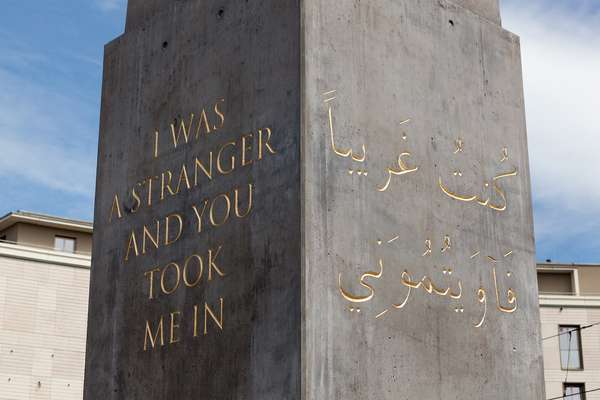

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

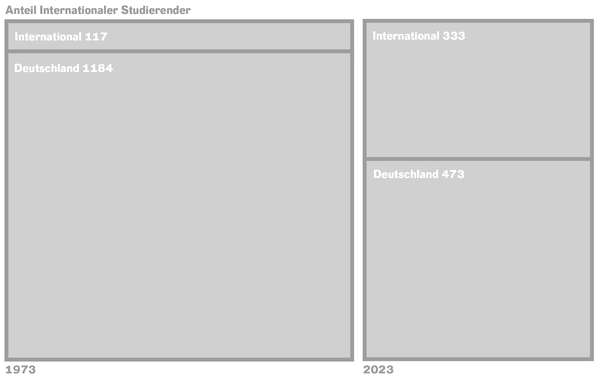

Diversity

Diversity

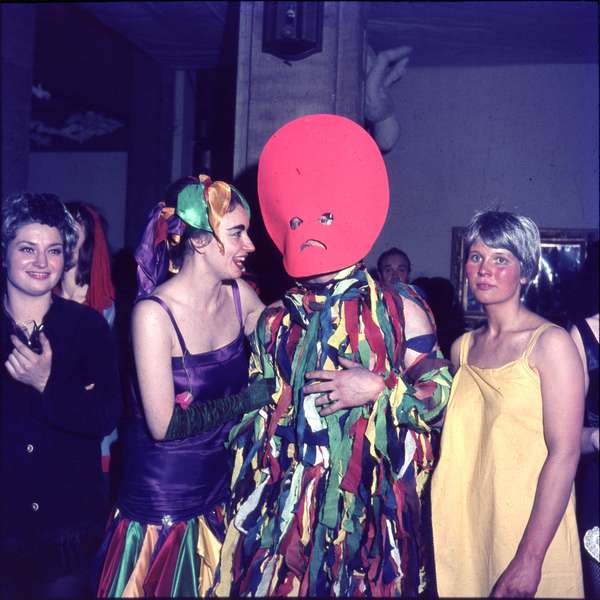

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

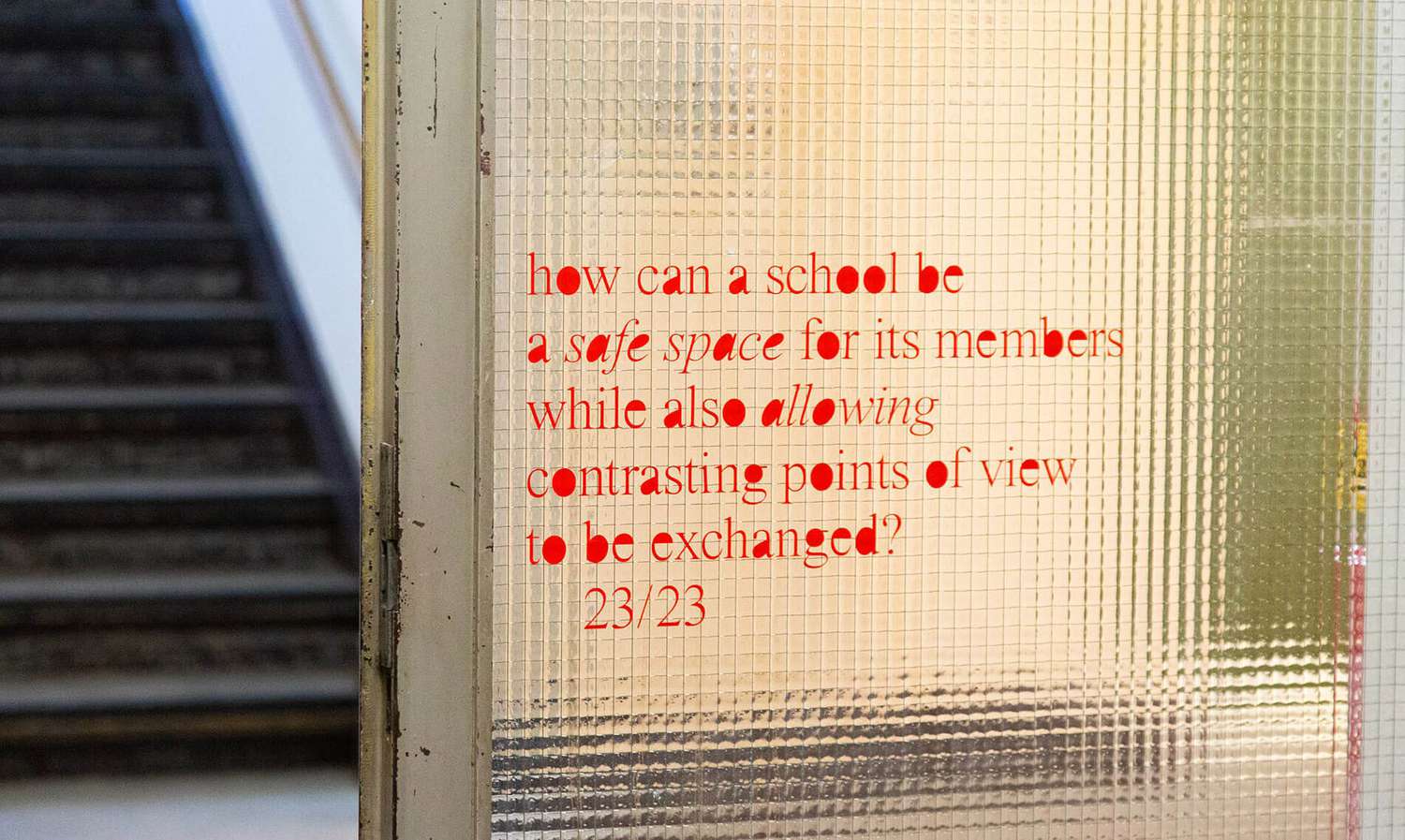

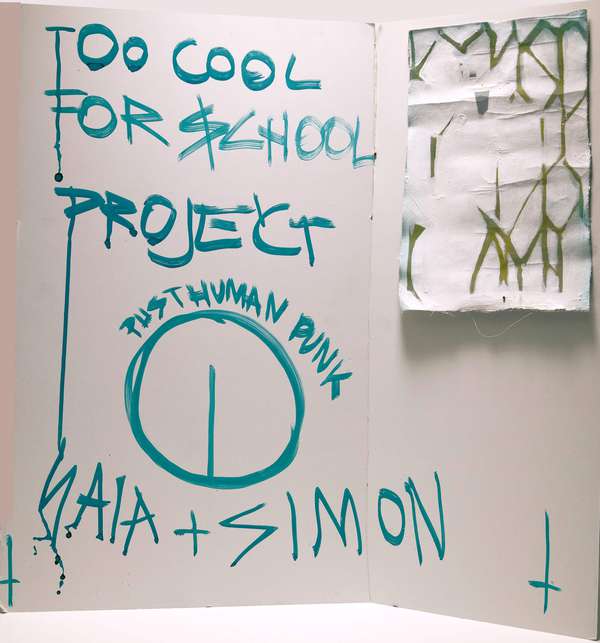

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

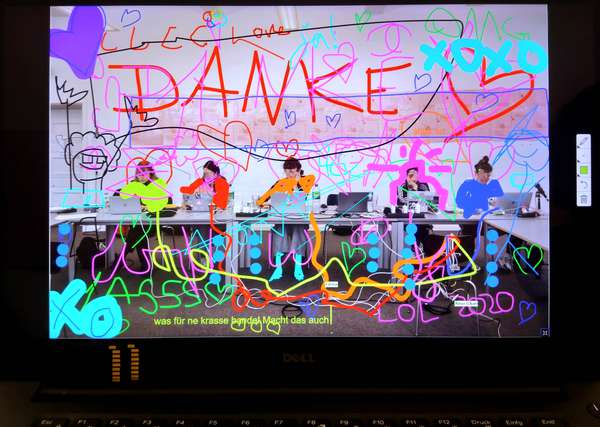

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

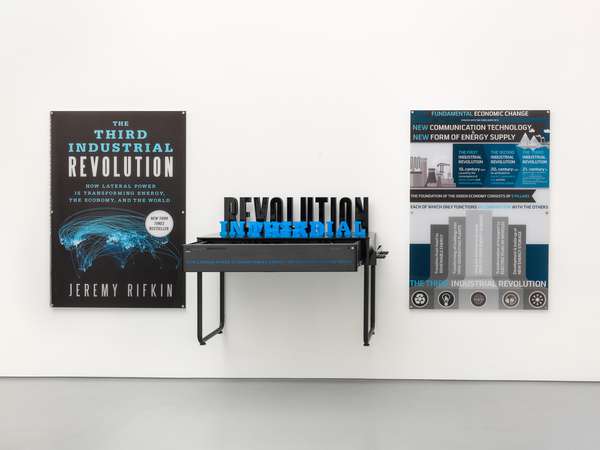

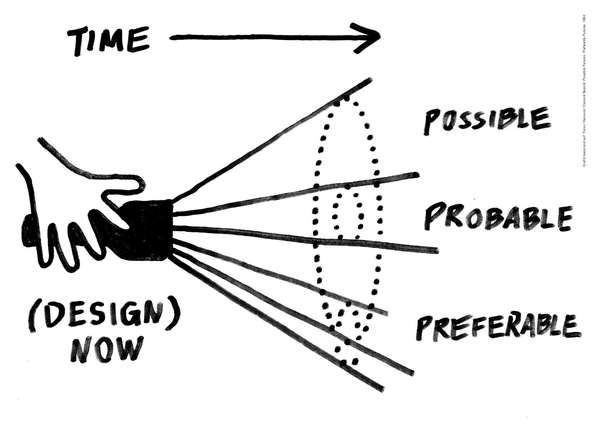

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?