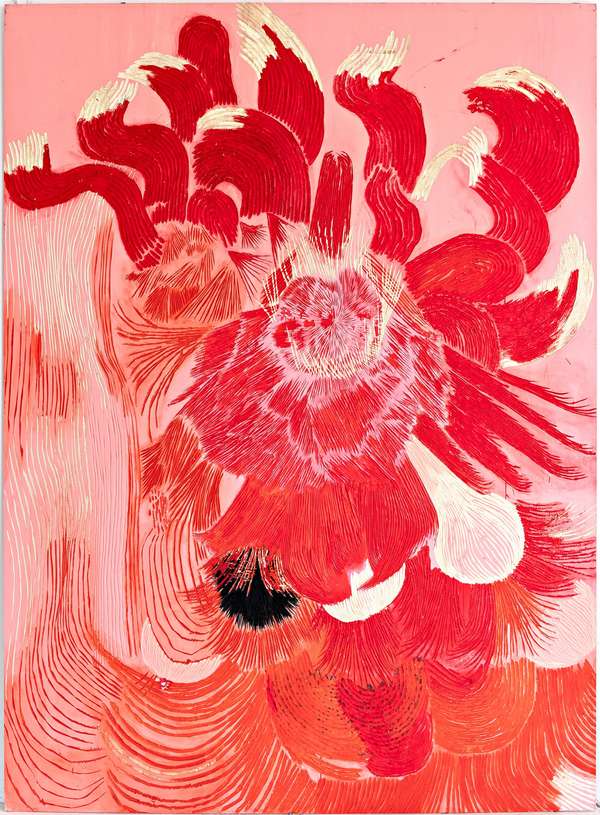

Grand Theft Auto. Kristian Vistrup Madsen about Frieda Toranzo Jaeger's artworks

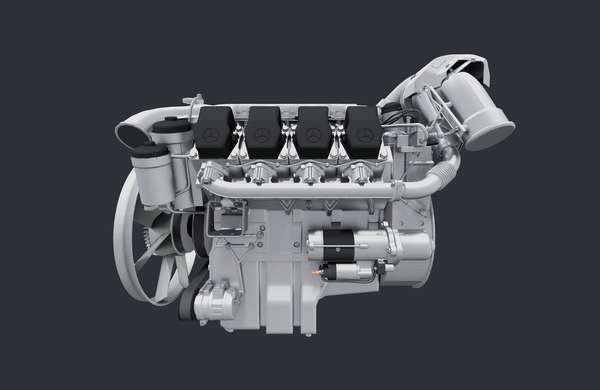

Hot, wet women caressing cars with soapy sponges, and sweaty mechanics in dirty tank tops, their wrenches and pliers symbolic substitutes for the phallus—these are the protagonists of our culture’s widely held erotic fixation with cars. At the center of it, of course, is the engine, the heir to the horse’s age-old status as the ultimate emblem of virility. Frieda Toranzo Jaeger’s work can be understood as a vandalization of this semantic field: she keys the paint of the car and takes it for a ride.

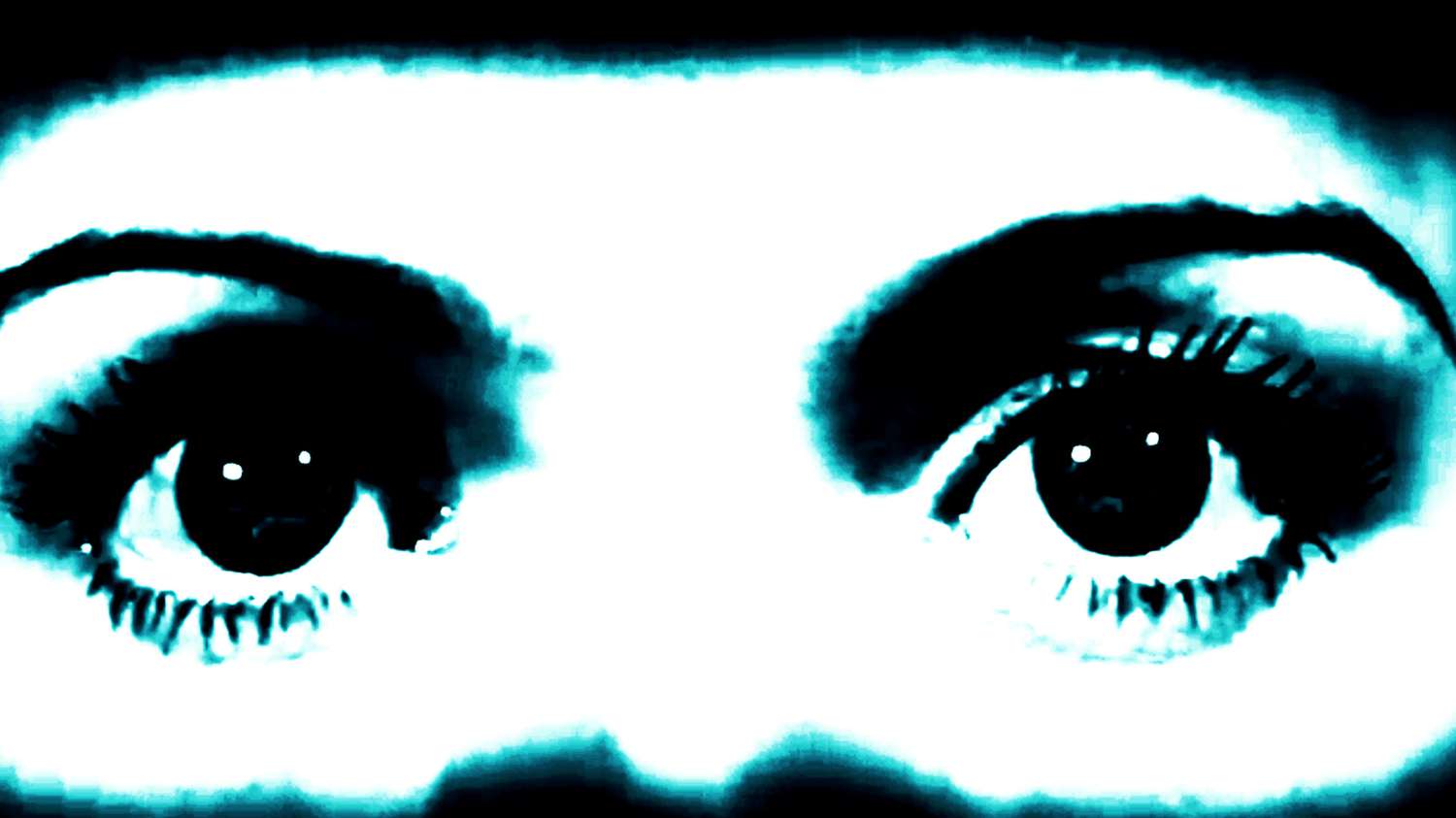

Auto-eroticism could be the title of a great many of her works, though, so far, it is the title only of one: a tripartite painting of the underbelly of a car, with its various tubes and parts sensuously fingered by pink hands. In its straightforward sense we could translate auto-eroticism simply as “car sex,” a motif—two people, women, fucking on the back seat—that appears in several of Jaeger’s works, for instance Tapicería Nocturna (2017) and Sappho (2019). To use the term of the scholar José Esteban Muñoz, we could call this a form of disidentification: to mobilize, or even luxuriate in, the power of long-established notions—say, the relationship between the virile and the phallus, or otherness and the exotic—but in doing so, rewiring their logic. The car appears in Jaeger’s works with all the horsepower of cultural hegemony, but to other, more ambivalent ends.

And, as in anything even vaguely related to psychoanalysis—the language of which Jaeger’s work is steeped in—ambivalence is key. Auto derives from the Greek word for self, while Eros has to do with desire, something usually aimed at what the self is not. But also, as Sigmund Freud so famously posited, the erotic is powered by death drive. The roar of an engine, speed, is sexy because it connotes danger, anticipates destruction. Sex cannot be disentangled from self-annihilation, whether of a romantic or sadomasochistic nature. There is a contradiction, then, between the car as a form of self that moves through the world and the presence of the erotic, which simultaneously affirms the self and negates it by making it at once the subject and the object of desire. And so we can understand the interior of the car as a complex psychological sphere, and Jaeger’s painting Autoeroticism as a portrait of the circuitous ways of the subconscious.

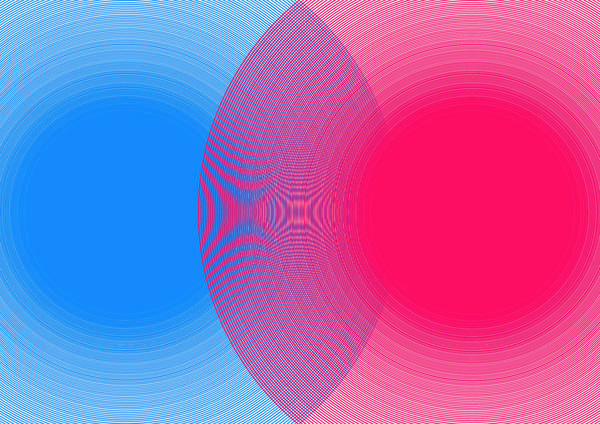

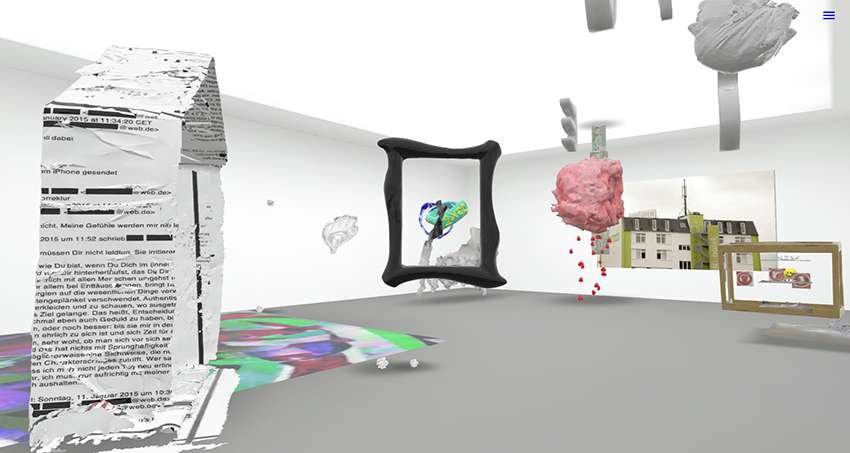

Free-standing and divided into several panels, Jaeger’s paintings are often reminiscent of altarpieces. At a time when most painting was done directly on the wall, the altarpiece was autonomous—like a car, it moves. But whereas a gothic painting would traditionally be read like a book, from left to right, birth to death, Christmas to Easter, Jaeger’s are circular. In Autofellatio (2020) the viewer’s gaze begins with the mechanical contraption at its center and moves outwards in a spiral. Hope the Air Conditioning Is On While Facing Global Warming (Part 1) is another car interior and another point of access to the subconscious. Like a Rorschach test, it opens diagonally upward to both sides, producing a dynamic mirror effect that is enhanced by the supple curves of the car. Autoeroticism repeats this composition, but manically, the dense undergrowth of the car, with its twisting tubes, making a flurry of circles. Here is a closed circuit that endlessly feeds back into itself. This is part of what makes it a self and secures its autonomy. It is also what closes it off to the world. Again: ambivalence.

In Freud, auto-eroticism refers to a stage in the development of infant sexuality in which desire does not have an object but is oriented toward the subject’s own genitals. The Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler used Freud’s theory as the basis for his now so prevalent definition of autism, however, crucially excising the erotic, thus causing great dispute with Freud, who would never concede that the two could be separated. Autofellatio reads as a manifesto of masculine auto-eroticism: an autistic circle-jerk of toxic virility, which, in a bold gesture of disidentification, Jaeger signs with her name in great lightning bolt-yellow script. But at the same time, in this picture, every rod is also a hole, every line loops back to itself. The phallus is always also not.

The autofellationist is someone who can such his own cock, a maneuver that will bend his body into a circle not unlike those that repeat throughout Jaeger’s oeuvre. It is at once autistic, narcissistic, as well a non-reproductive sexual act that breaks with a heteronormative pattern—more than ambivalent, it is multivalent. A 2001 article in the US porn magazine Hustler suggests the practice might actually be illegal:

Eighteen states have sodomy laws on the books, banning oral sex between two consenting adults. Could an overzealous district attorney extend the blowjob ban to a single consenting adult? “You never know; it might fly,” says a criminal defense attorney, who wishes to remain anonymous. “I wouldn’t be surprised in the least if a law prohibiting autofellatio were upheld by the present Supreme Court.”

Though somewhat far-fetched, the example does point to the subversive aspects of the auto-erotic: how it breaks with linearity and dismantles the boundaries of subject and object. We see this when in several of Jaeger’s works the high-tech aesthetic of artifice and mechanics associated with cars blends at its edges with unruly natural elements like fern leaves and thorny branches. Where the auto points inward, the ex- of exotic, like the ex- of existence, refers to the outside. A tension which Jaeger very often sustains in her works is that between the private and public spheres. The decision of the US Supreme Court in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), which put into effect the sodomy laws mentioned in the Hustler article, and would not be overturned until 2003, Muñoz reminds us, “efficiently dissolved the right to privacy of all gays and lesbians, in essence opening all our bedrooms to the state.” Transgressions of the private sphere are structural and political; they are part of how the system works. The solution that Muñoz proposes, and which we see enacted with such force and humor in Jaeger, is to disidentify, and drive the eros in your auto to the exos on your own terms.

The power of transgressing the private sphere relies on the scandal of revelation: that there would be a shameless secret to uncover, an illusion to break. Jaeger’s works are three-dimensional set pieces, asking the viewer to move around them in order to see their empty backsides, and see that the depth they purport is literal, produced like on a theater stage. In Autofellatio the central component hangs directly on the wall, while the smaller panels which form a circle around it are suspended from the ceiling at a distance. The integrity of the work does not hinge on the illusion of a unified plane being maintained—quite the opposite. Jaeger bares its construction as a vampire bares their fangs, in a mode at once confrontational and flirtatious. Others are like folding screens, alluding to a sense of bashfulness entirely misplaced in the world of these works where the inside of the car is the outside of the painting, and sex is always already both private and public. In Jaeger’s works there is no scandalous return of the repressed. More than merely honest, they are frank, and demonstratively so; they take pleasure in no nonsense. And this is also what guarantees their fierce autonomy.

Still, the very idea of autonomy in painting, as well as the automatism of a car, remains a source of conflict in the works. The fact of the auto as a self, effectuated in the promise of the driverless cars of the near future, is a challenge precisely to the autonomy of those inside it—a threat to the Freudian drives, to desire and virility. Does the car’s agency strip us of our own? Sappho (2019) is the work in which ultimate interiority, the auto-erotic space of the car, most completely collapses into the ex- of the exotic, eclipsing the relation of self to other. Two women have oral sex, sprawled across three car seats in black leather, thick and taught like the torsos of gorillas. They are surrounded by a lush junglescape reminiscent of Henri Rousseau’s fantasies of the wild, and joined, absurdly, by several Pomeranian lapdogs. Here Jaeger offers a rather sober response to panicked questions about castration anxiety and the waning of libido posed by the self-driving car: When no one has to worry about steering the car, surely that just leaves us with more time to get on with the task at hand. Sappho portrays activity and passivity dissolved into a murky in-between: a fucking which is not aimed at ejaculation, a trip without a destination, without end.

Such a picture puts pressure on the distinction Freud so wanted to maintain between wanting the other and wanting to be the other—that is, between desire and identification. In Identification Papers, Diana Fuss marks that distinction as “precarious” at best. She revises Freud’s theory by proposing instead “vampirism” as a mode, which is

both other-incorporating and self-producing; it delimits a more ambiguous space where desire and identification appear less opposed than coterminous, where the desire to be the other (identification) draws its very sustenance from the desire to have the other.

This vampiric style of agency is not endangered by the contradiction between auto and eros. Rather, it understands autonomy as something that does not require authoritarian transgressions such as Bowers v. Hardwick in order to sustain itself, but in fact thrives on mutual contamination. This logic unlocks the vast amount of energy and dynamism we see in Jaeger’s works, with their circular compositions and strong sense of velocity. “Speed is not very often applied in painting,” Jaeger said to me, “I wanted to know: how do you make a painting fast?” It has to do with getting the wheels of desire moving—to hijack the biggest car you can find and push it down a hill.

Text by Kristian Vistrup Madsen. It will be published in the catalogue accompanying the Finkenwerder Art Prize exhibition 2022.

Works Cited

- José Esteban Muñoz: Disidentifications, University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

- Dan Kapelovitz: “Because They Can: The Risks and Rewards of Auto-Fellatio,” Hustler, January 2001.

- Diana Fuss: Identification Papers: Readings on Psychoanalysis, Sexuality, and Culture, Routledge, 1995.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

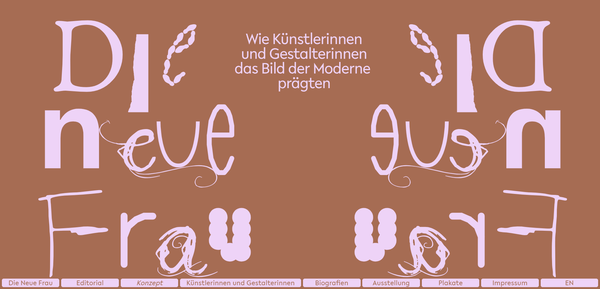

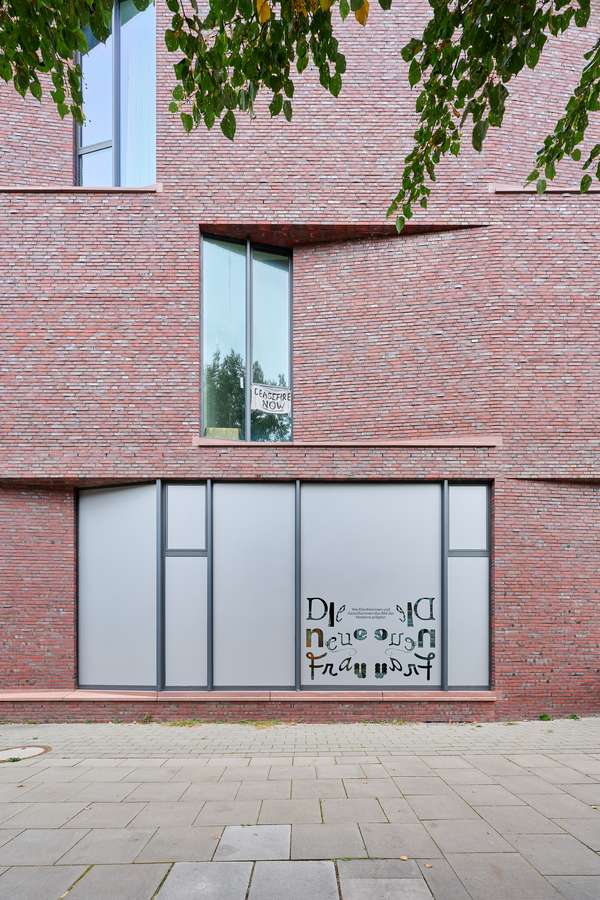

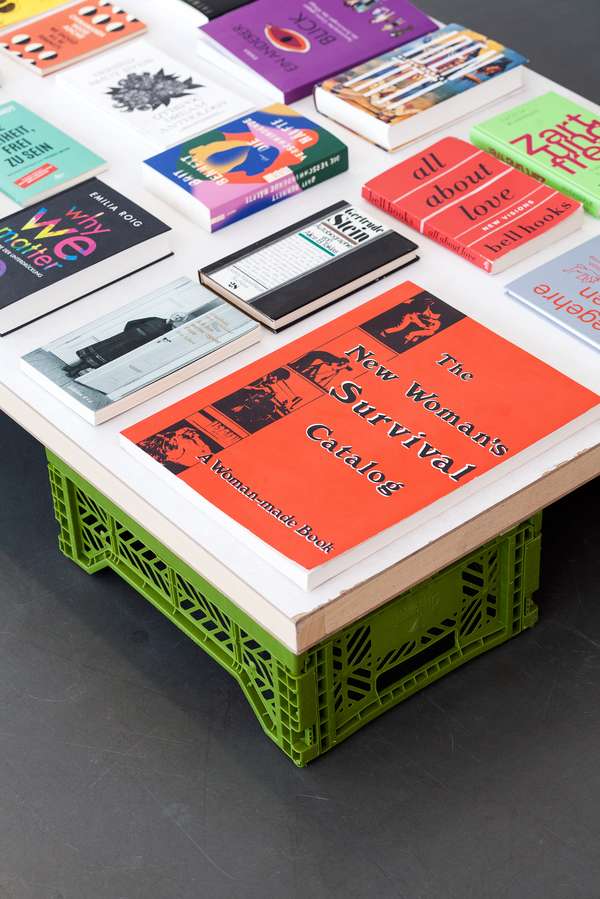

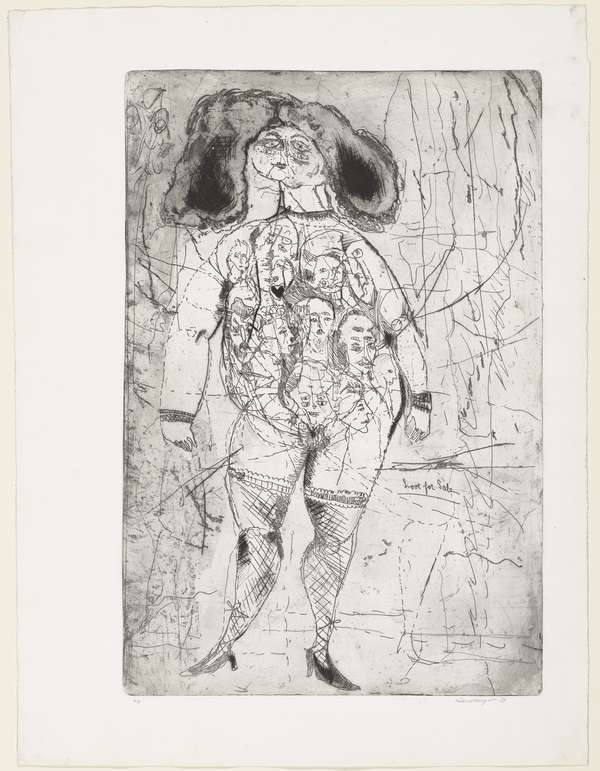

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

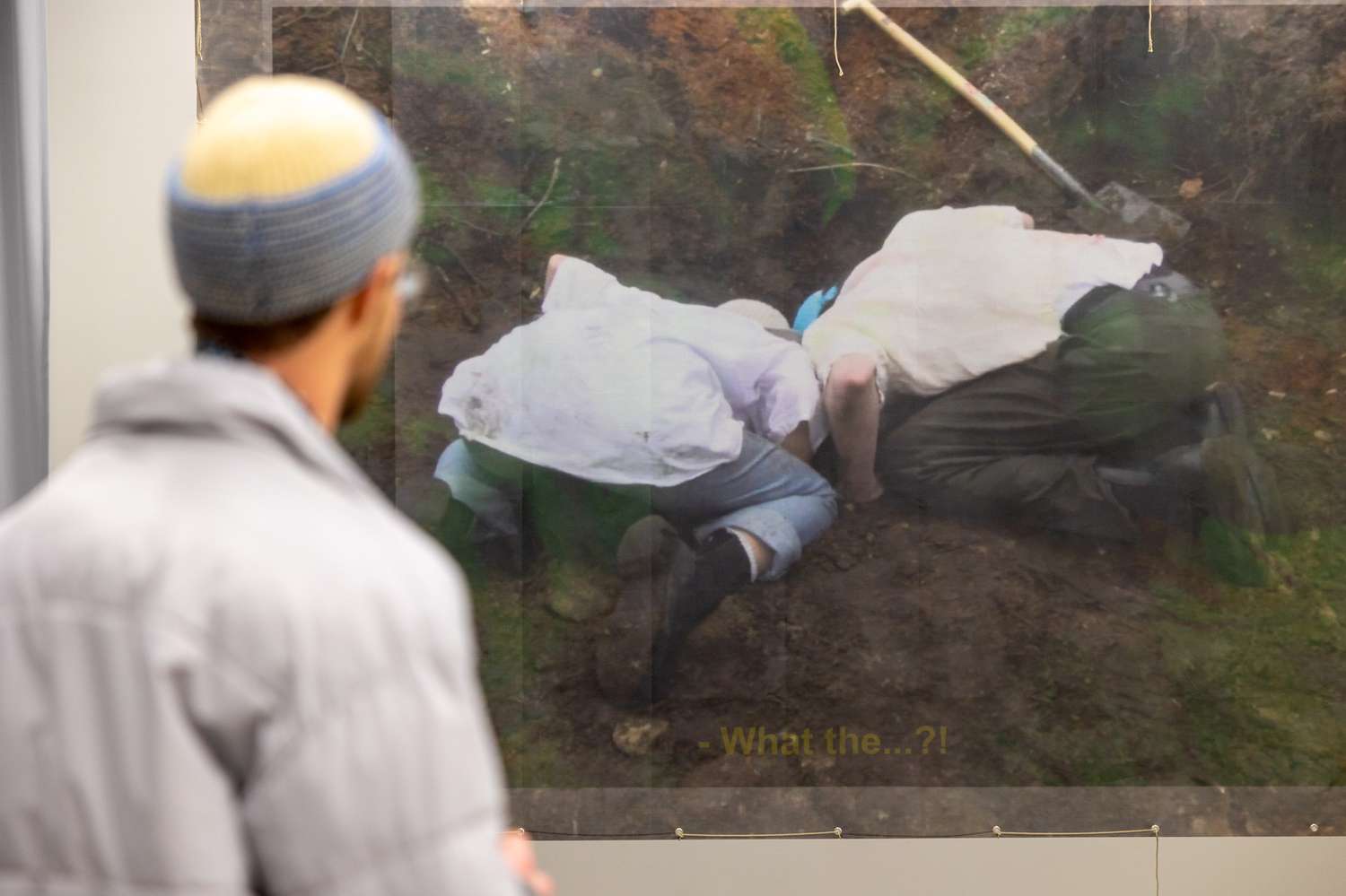

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

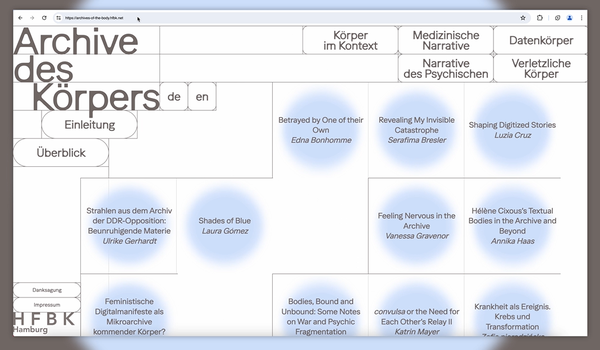

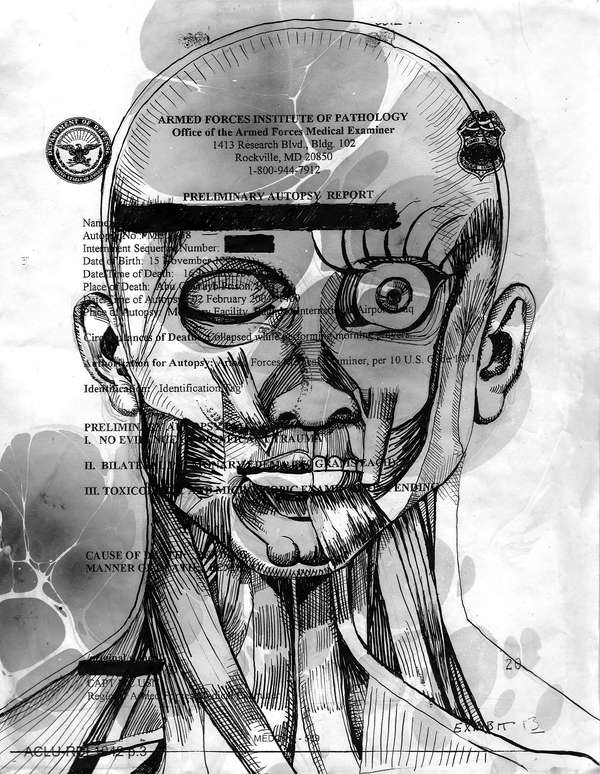

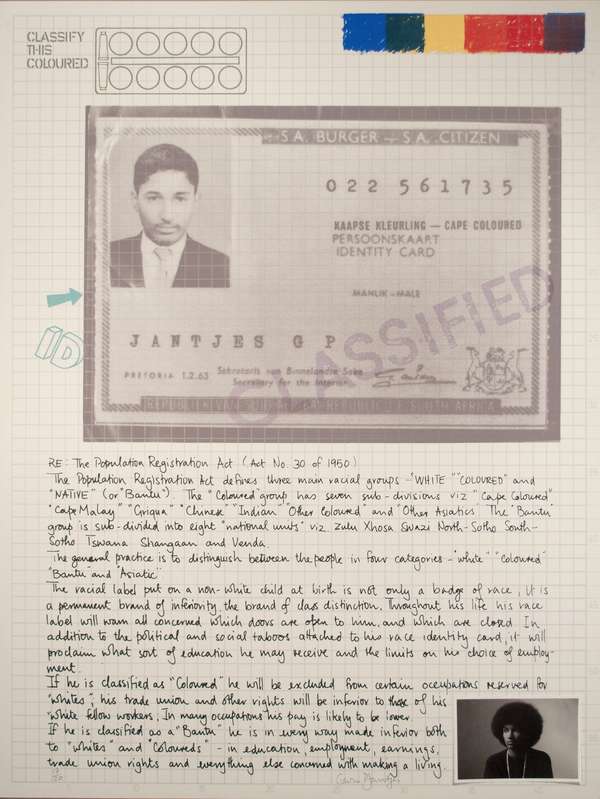

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

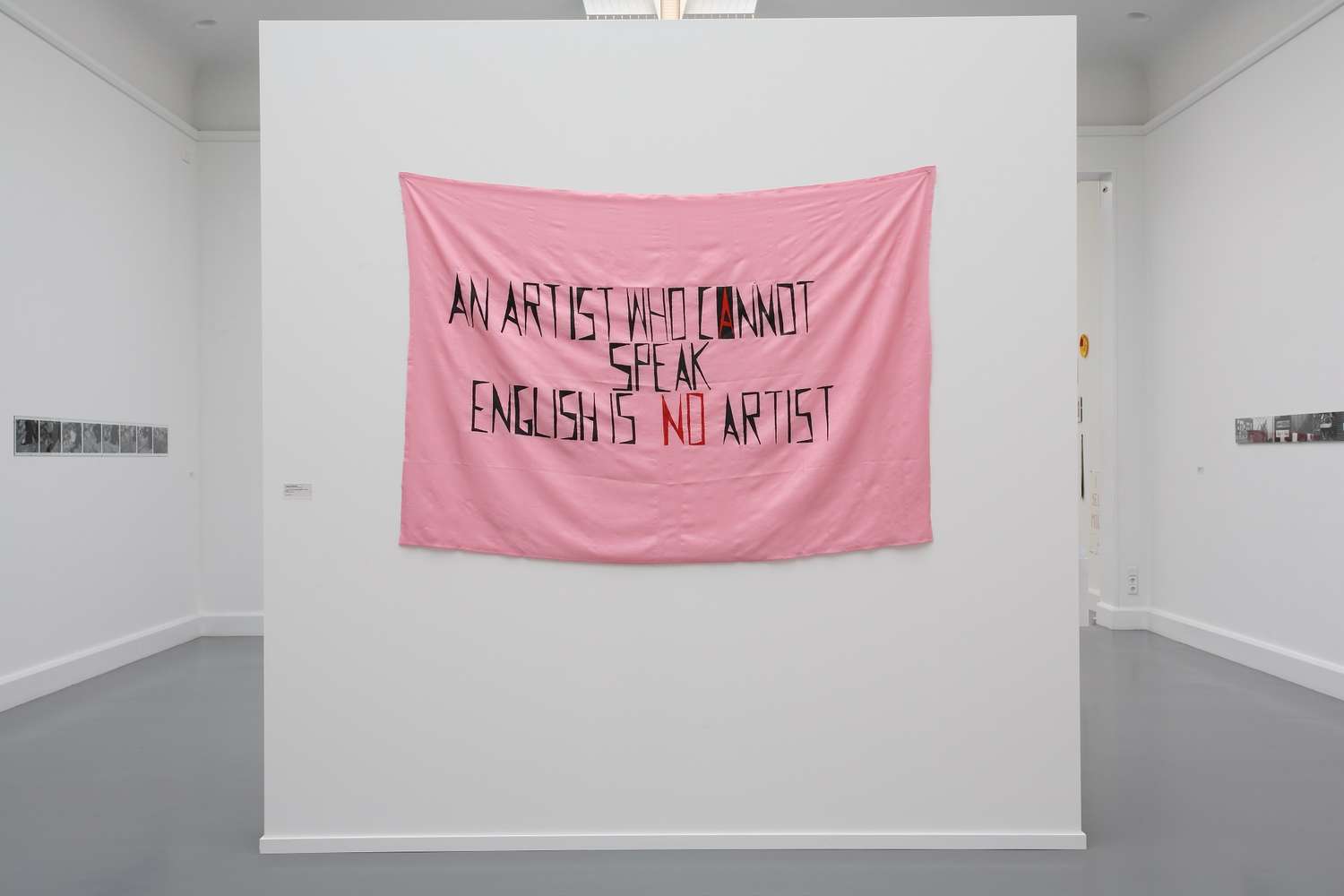

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

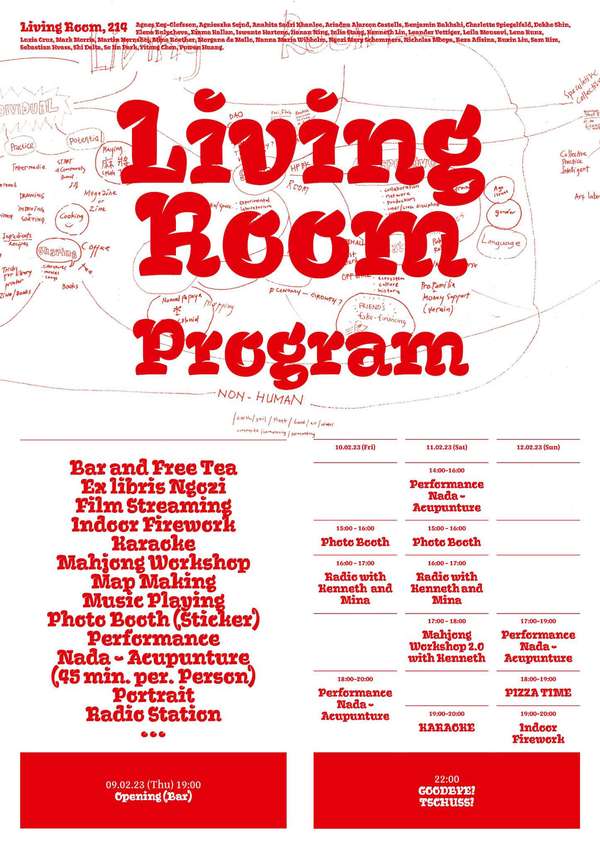

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

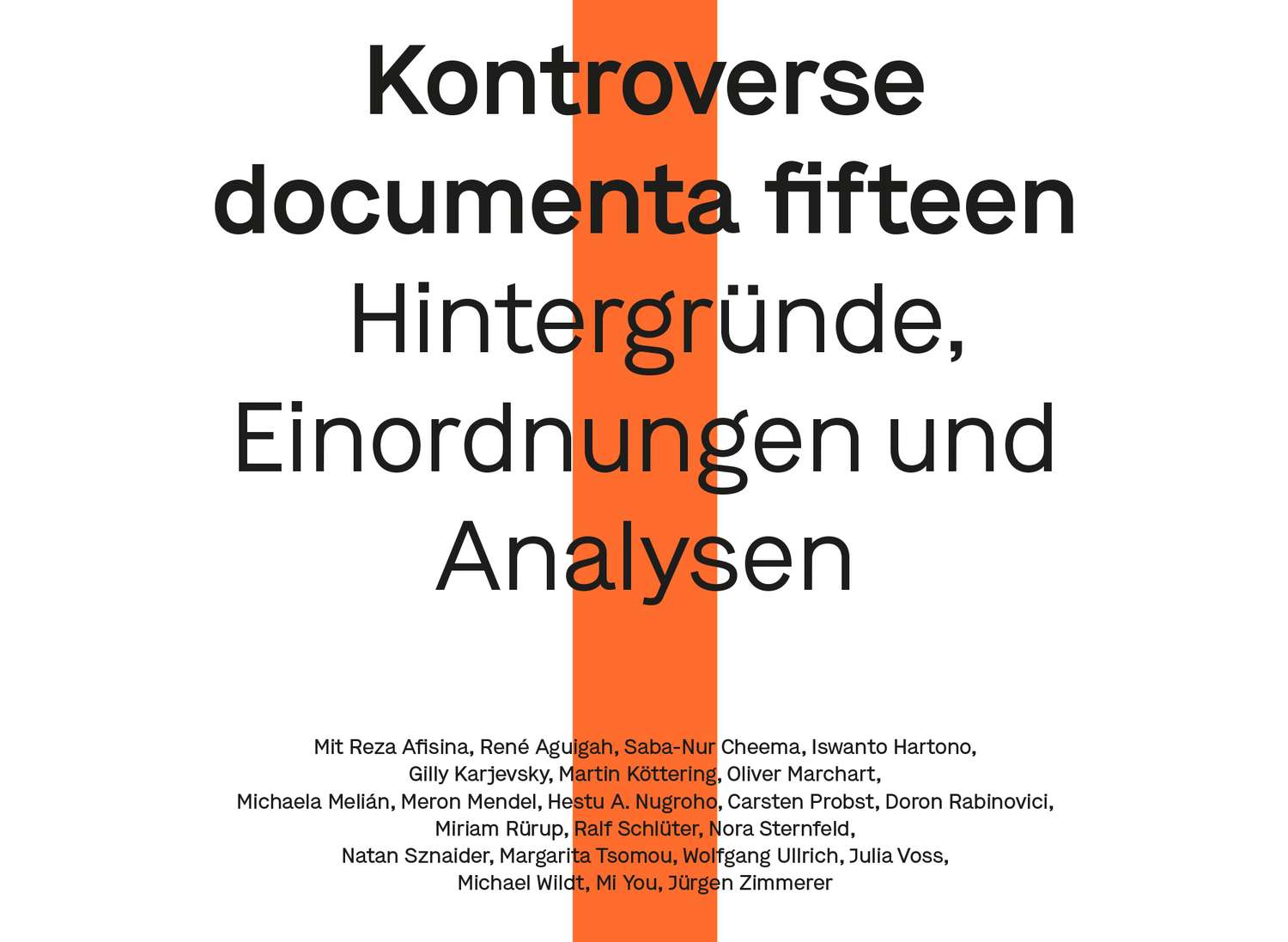

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

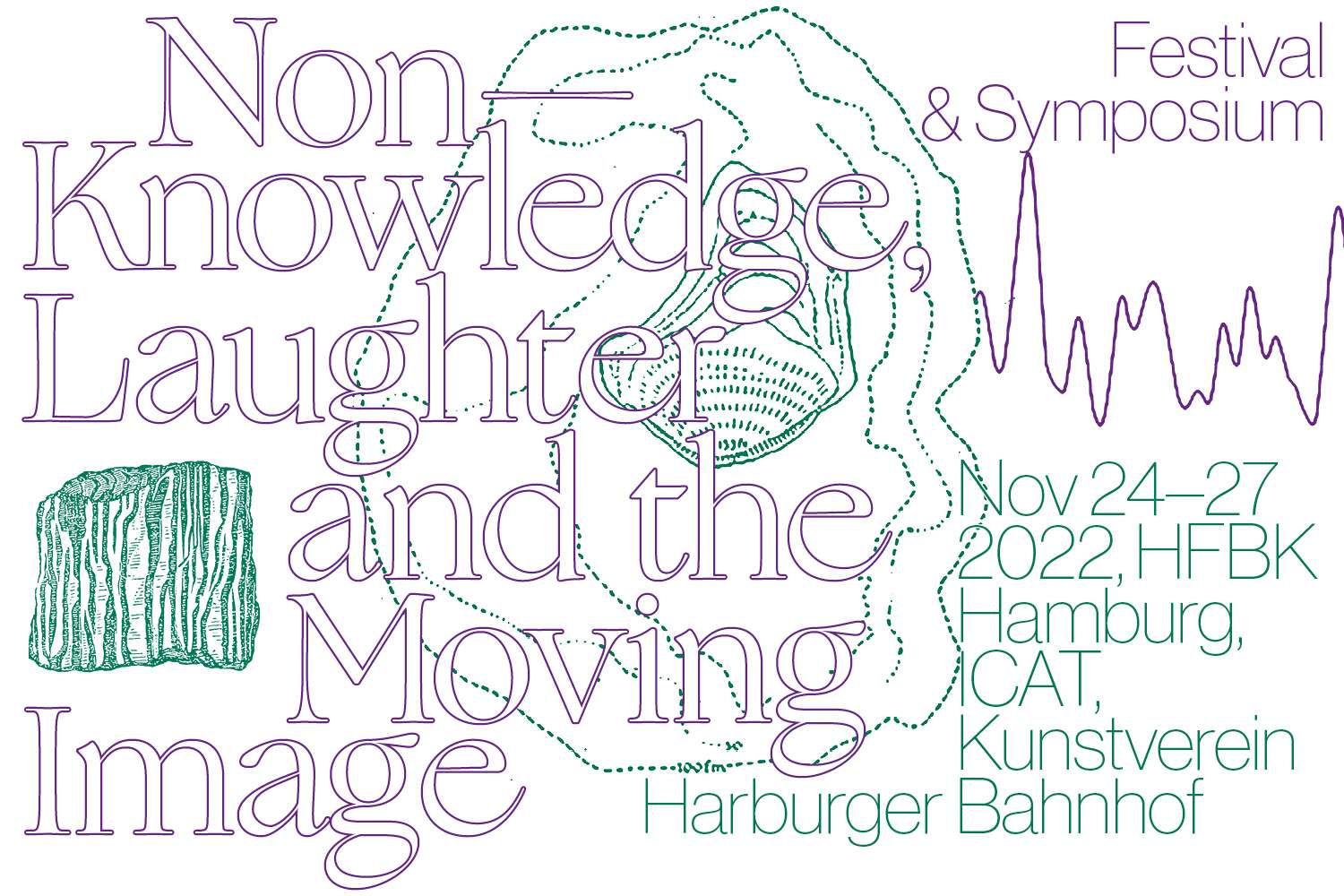

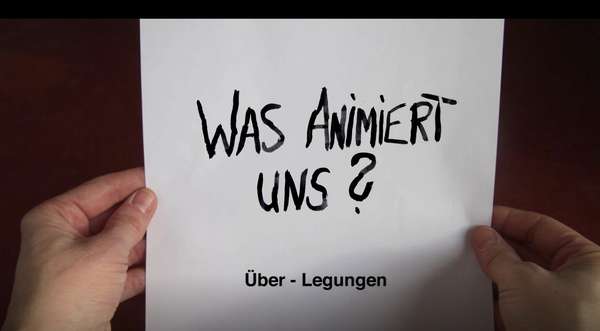

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

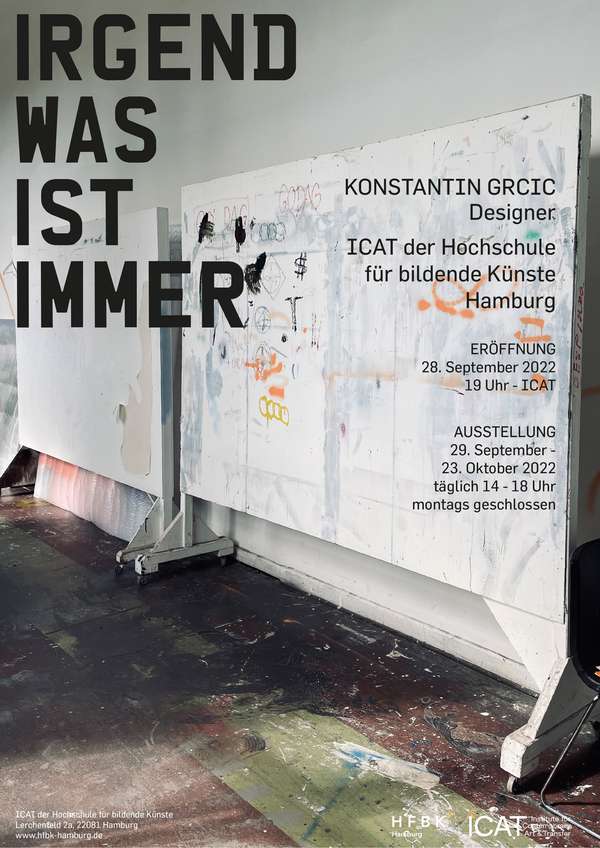

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

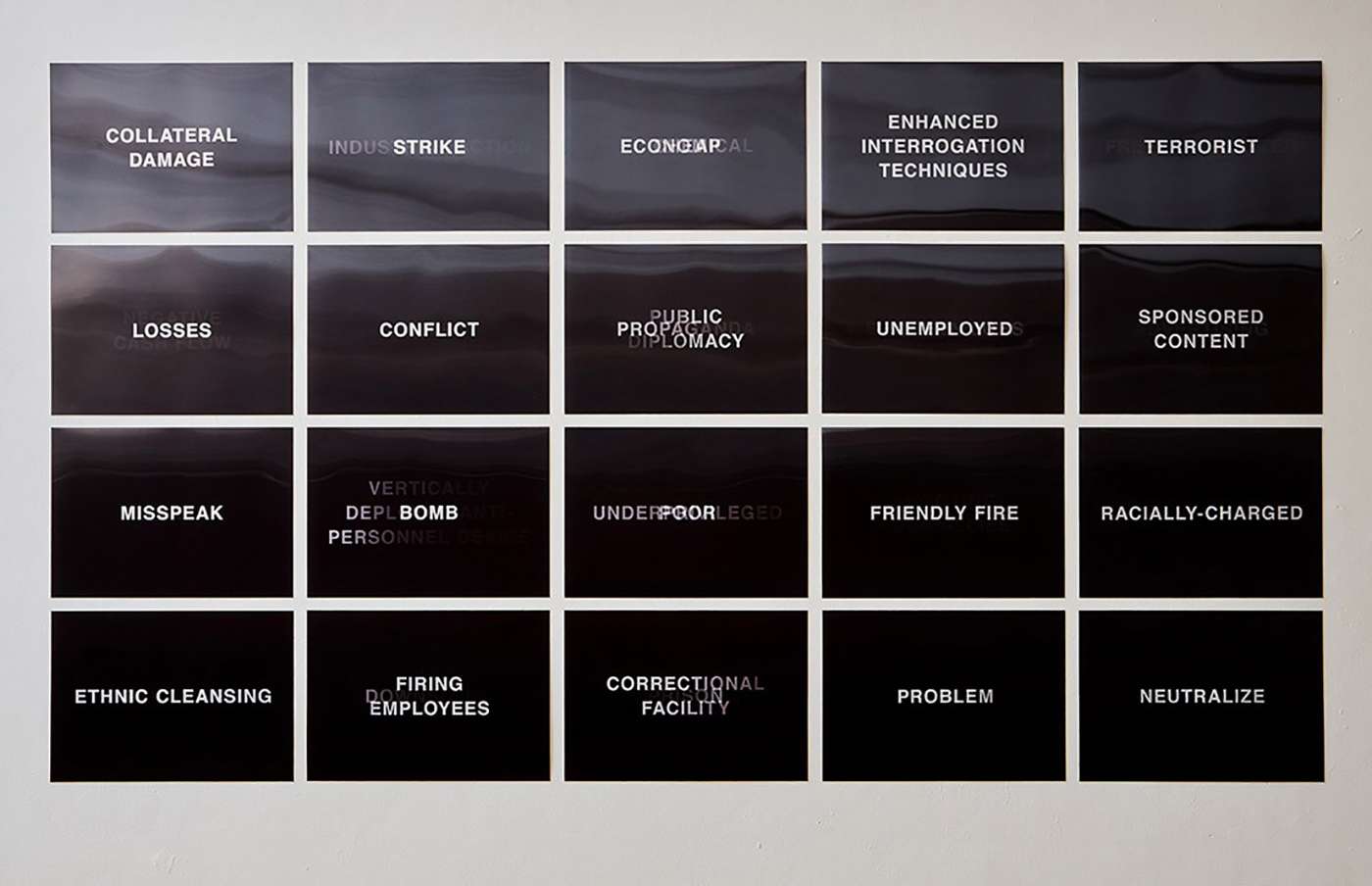

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

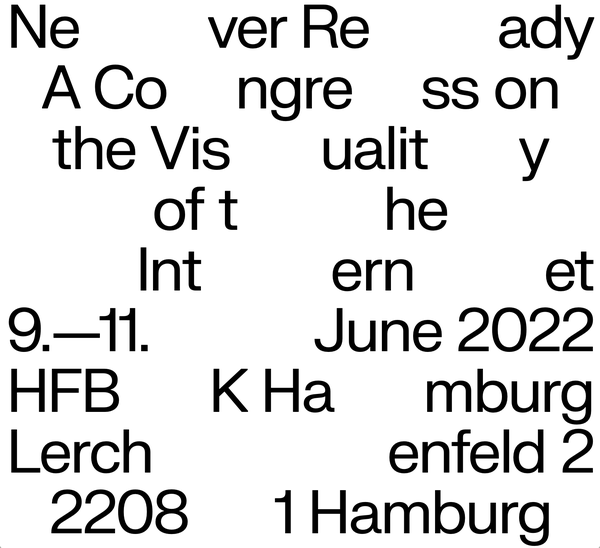

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

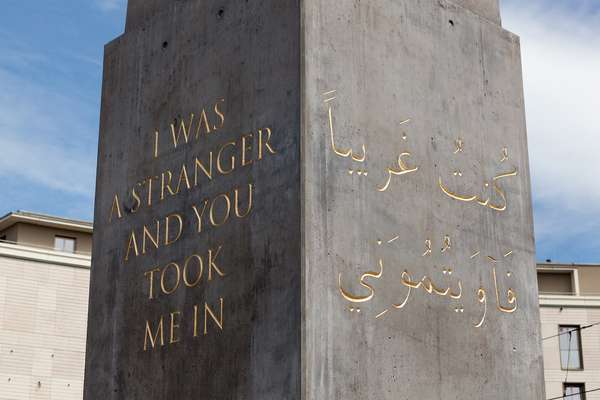

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

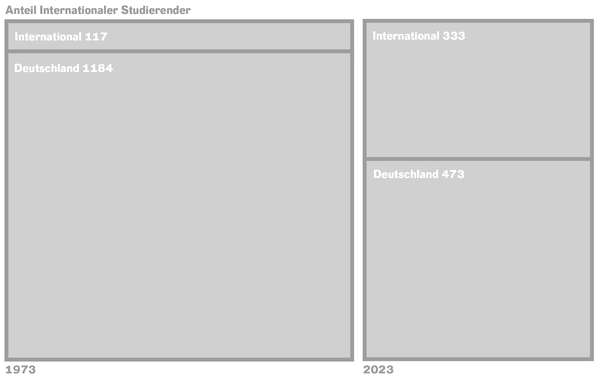

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

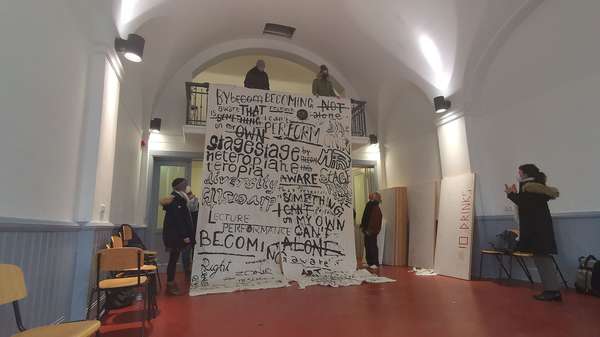

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

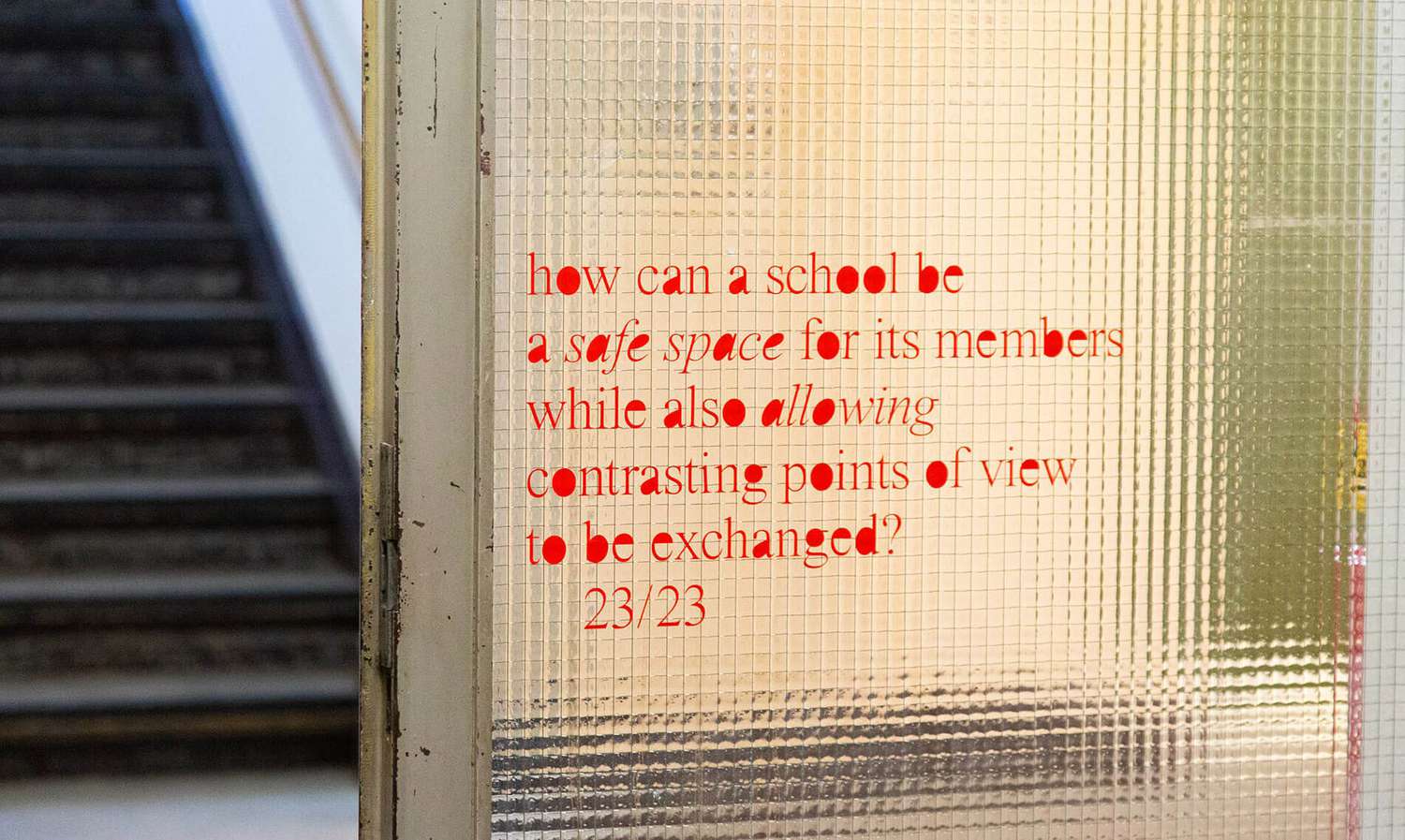

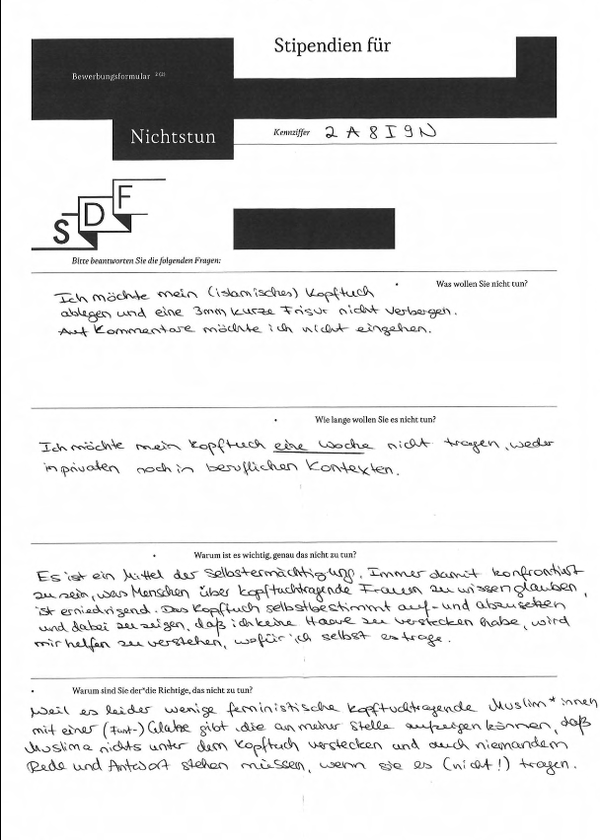

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

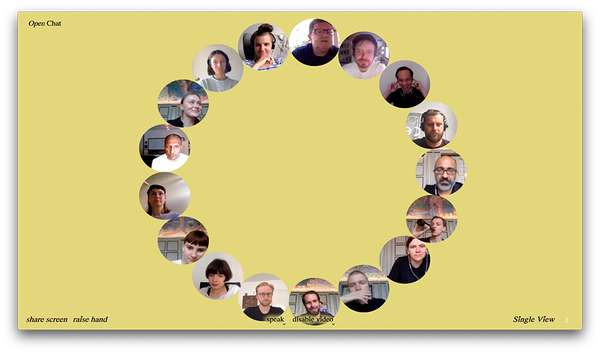

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

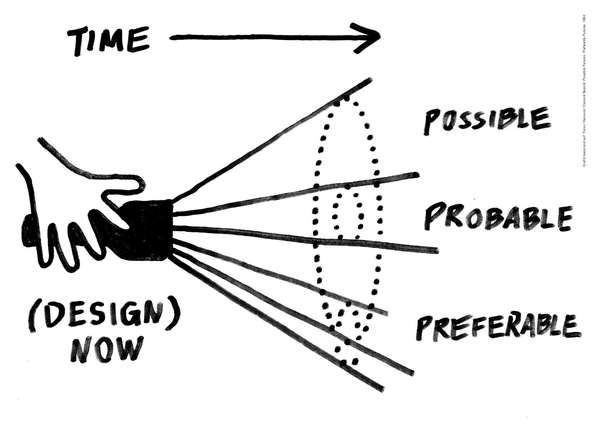

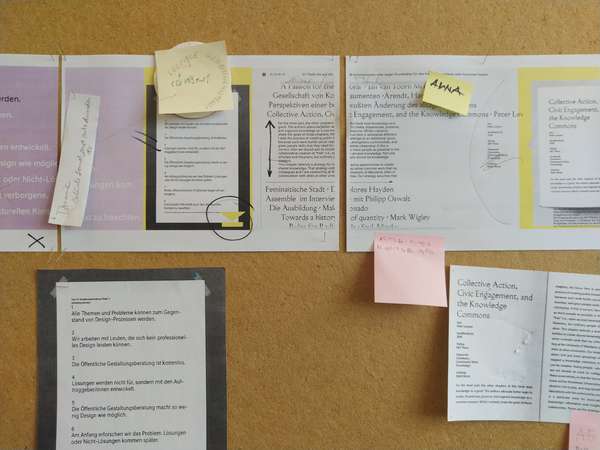

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?