Construing remembrance as an active process

Michaela Melián (Professor of Time-based Media) and Dr. Nora Sternfeld (Professor of Art Education) have for many years concerned themselves in different places and in a variety of projects with historico-political interventions along the interface of art, theory, and activism. When they met up in 2020, now as professors at HFBK Hamburg, the idea arose of hosting a joint seminar which is now culminating in a conference. The objective is to team up to think about the options for, difficulties of, and urgency of remembrance – for the future.

Michaela Melián: In Germany, which is often termed “the remembrance world champion”, the official culture of remembrance and the related discourse has evolved over many decades. Since Reunification of East and West Germany a little more than 30 years ago, the debates on how history should be approached have become compelling in a new way for society as a whole. This also has to do with the fact that hardly any survivors of the Shoah are now still alive to bear witness to it and, at the same time, right-wing discourses and violent deeds motivated by racism, such as those by the NSU, have truly surged. Against this background, various parties have suggested by way of accusation that Germany has gone too easy on itself in the mode of working through that history and has ignored current trends in the process. Moreover, today a postcolonial angle on the Shoah needs to be considered. By comparison, Austria plays a different role in the discourse on remembrance. There, for many years the comfortable idea prevailed that the perpetrators were to be found in Germany. Thus, there was not a student movement there in 1968 that came out in criticism of the generation of its parents. Artists, writers, directors, and other cultural producers in Austria who explored the relationship to the Nazis were subject to strong public scorn and animosity. An example would be Elfriede Jelinek, who in her plays and texts places her finger in precisely these wounds. In recent years, there has been an increasing number of campaigns and ideas from Austria that radically and uncomfortably question existing types of forms of remembrance. How do you as an Austrian assess the current status in the two countries on remembrance policy and the associated debate?

Nora Sternfeld: Remembrance – in the sense of public remembrance such as takes place at places of remembrance as in monuments and memorials – is a result of struggles, it is fissured, ruptured, brittle, controversial, and repeatedly has to be reformulated in the present with a view to the future. However, I have the feeling that in Germany a hegemonic “culture of commemoration” has since 1989 replaced critical remembrance work. Remembrance as struggled for seems to have been achieved, but it is also ritualized, emptied, and economized. Things were different in Austria: Here the issue was and continues to be to struggle and wrestle with things. And, as a result, I feel the cutting-edge historico-political projects in Austria are explicitly more bellicose, while those in Germany are more nuanced, function more reflexively.

Melián: Is that not also a very recent achievement? In the past, activists were surely more sceptical toward artistic interventions?

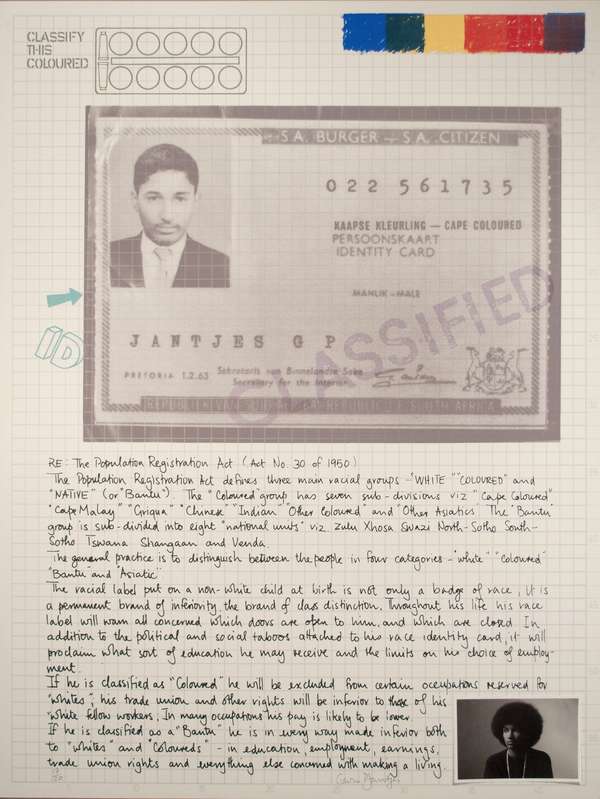

Sternfeld: That is not entirely true as regards Vienna. Artists there were also activists and vice versa. Perhaps because it was later that it all started happening there … But it is hard to say without generalizing. There is a lot of interaction and much common ground between the activist and artistic forms of action. All in all, in the course of the 21st century to date both in Germany and in Austria we have witnessed how the critical focus on Nazi history has been diluted by giving it greater state-driven gravitas – while this suddenly seems to have emerged as the master narrative, the battle zone has been expanded to include remembrance. And it was in the midst of these shifts in policy on history and in the official culture of remembrance that, perpetrated by the NSU, Nazi murders took place in Germany again. And once again they were wiped from memory, ignored, and once that no longer became possible, they were as far as possible marginalized. What does it signify for the work of remembrance if we are forced to say that formulaic remembrance rituals to the Nazi crimes have, on the one hand, become ubiquitous, and, on the other, remembrance of real Nazi murders and the associated demands that the crimes be solved are covered in a blanket of silence? Completely in line with this, cultural studies expert Peggy Piesche commented in an interview with the tageszeitung and from a BPOC position: In antiracist remembrance work, “we act like archaeologists, we are continually having to dig up our history. And the very next morning we have to start digging again, because sand has since been blown over it.” I believe this remembrance work with the wind in our faces forms the basis of our conference.

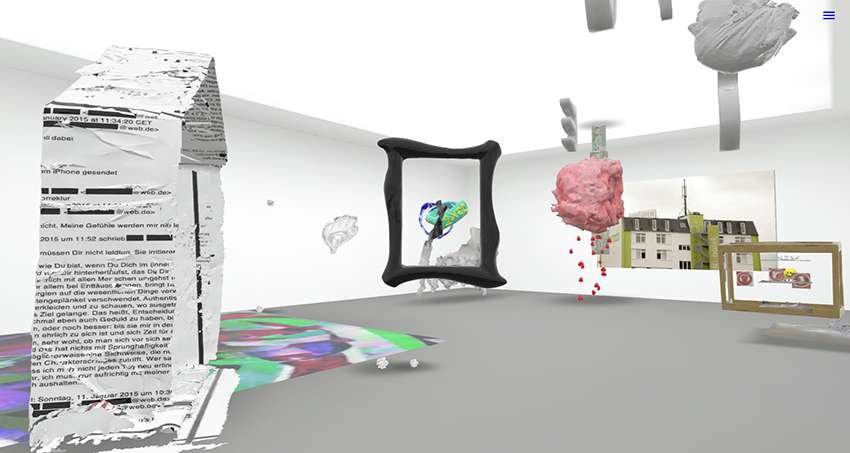

Melián: What is more, we also want to talk about what art and artistic interventions can achieve in the work of remembrance. The brief artists have is to find new forms for remembrance, to explore them with new means, media, and processes.

Sternfeld: So, from your point of view, what is it specifically that art can achieve?

Melián: Art can touch, disturb, provoke, and make people inquisitive without at the same time formulating a learning objective. It can document processes and/or store them so that they can be experienced anew; it can update things, but it can also cast them into question or ask new questions or ask questions anew. I am thinking here not just of the fine arts but likewise of literary works, movies, music compositions. For me, personally speaking, the film Shoah by documentary filmmaker and director Claude Lanzmann is of immense importance. What is it that is special for you, with your focus on art studies and art education?

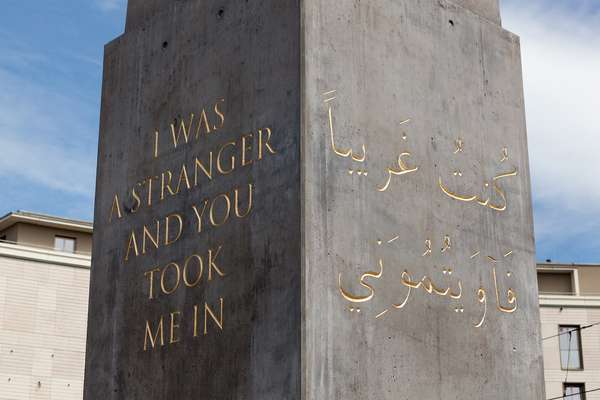

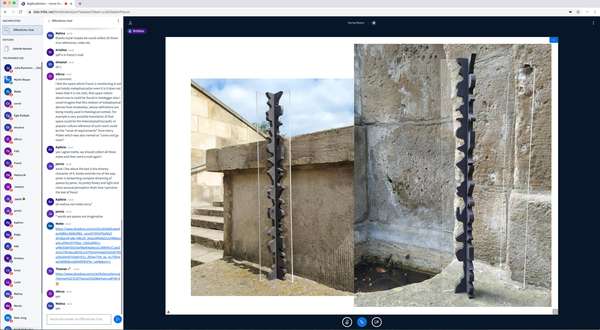

Sternfeld: For me, three potentials innate in artistic remembrance work are key: First, art has no claim to be neutral; it takes a stance and presents it. For that reason, artistic interventions were and are important elements in the struggles over remembrance. Second, art has an emotional dimension, it creates forms that forge links between what has happened and what could happen and above all raise questions as to what this means for the present. Claude Lanzmann’s oeuvre really is a good example in this regard. And your works are also important interventions between the documentary and the emotional. Third, art has the potential to act as a critical intermediary between participation and alienation. It definitely involves a history of reflexive inclusion, the invitation to square up to things. For me, counter-monuments and para-monuments are an artistic expression of these elements: They take a stance against the hegemonic historical narratives and at the same time open up spaces for critical interaction. They do not legitimate what is, and instead ask whom history “belongs to” and put this up for discussion in a radical democratic sense. However, not everything can always be realized exactly the way the artist conceived it. For example, works in public space are also the result of compromises. Last semester you reported on several occasions on the actual problems encountered realizing projects in the public space. Could you summarize your experiences in this regard?

Melián: Many of my works in public space in recent years were commissioned by municipal authorities and expected to fulfil a very specific function for remembrance policy. The projects are not perhaps overly comparable, but in principle I notice that the task of bringing certain historical occurrences into the present and thus into our minds is often assigned to artists. And the artists then have to balance a tightrope between their own standards for a successful artwork and the expectations of the client, meaning the political bodies and public – whereby the latter have usually been tussling for years over commissioning a work on the particular theme. What we repeatedly see is that the clients or the public do not then agree with the artistic proposals. Because precisely in the case of complex and emotional themes such as the Shoah, expulsion, discrimination, racism, and acts of terrorism, the expectation persists that what the client will get are strong, visual and emotional ideas. Whereas many artists today have strong reservations against autonomous artistic formulations that fill the urban space purportedly for all eternity. Rather, the artists seek solutions that construe remembrance as an active process in which they wish to participate through their work.

Sternfeld: Do you have an example in mind which fleshes that out a bit?

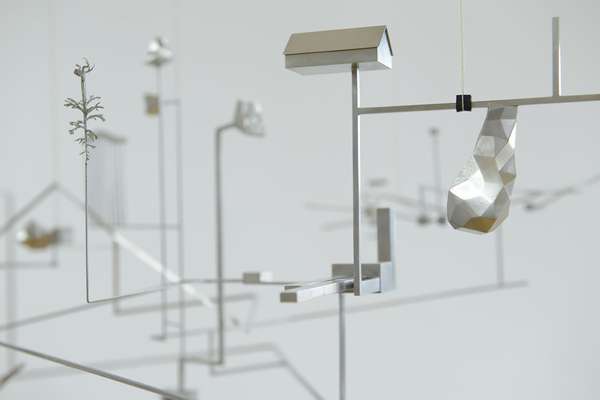

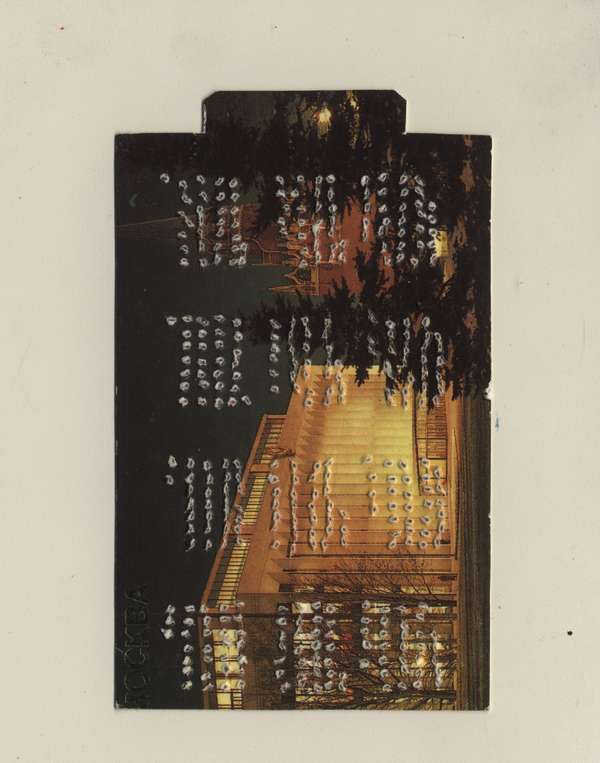

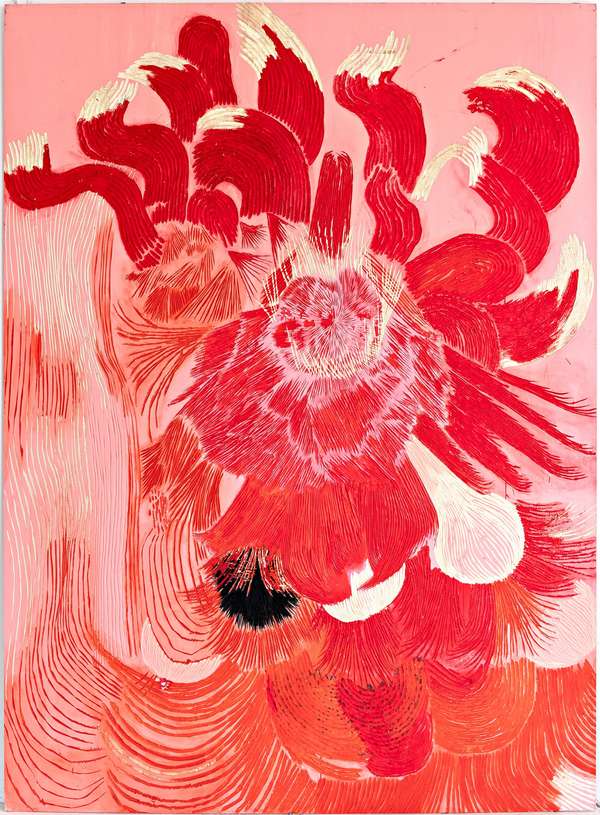

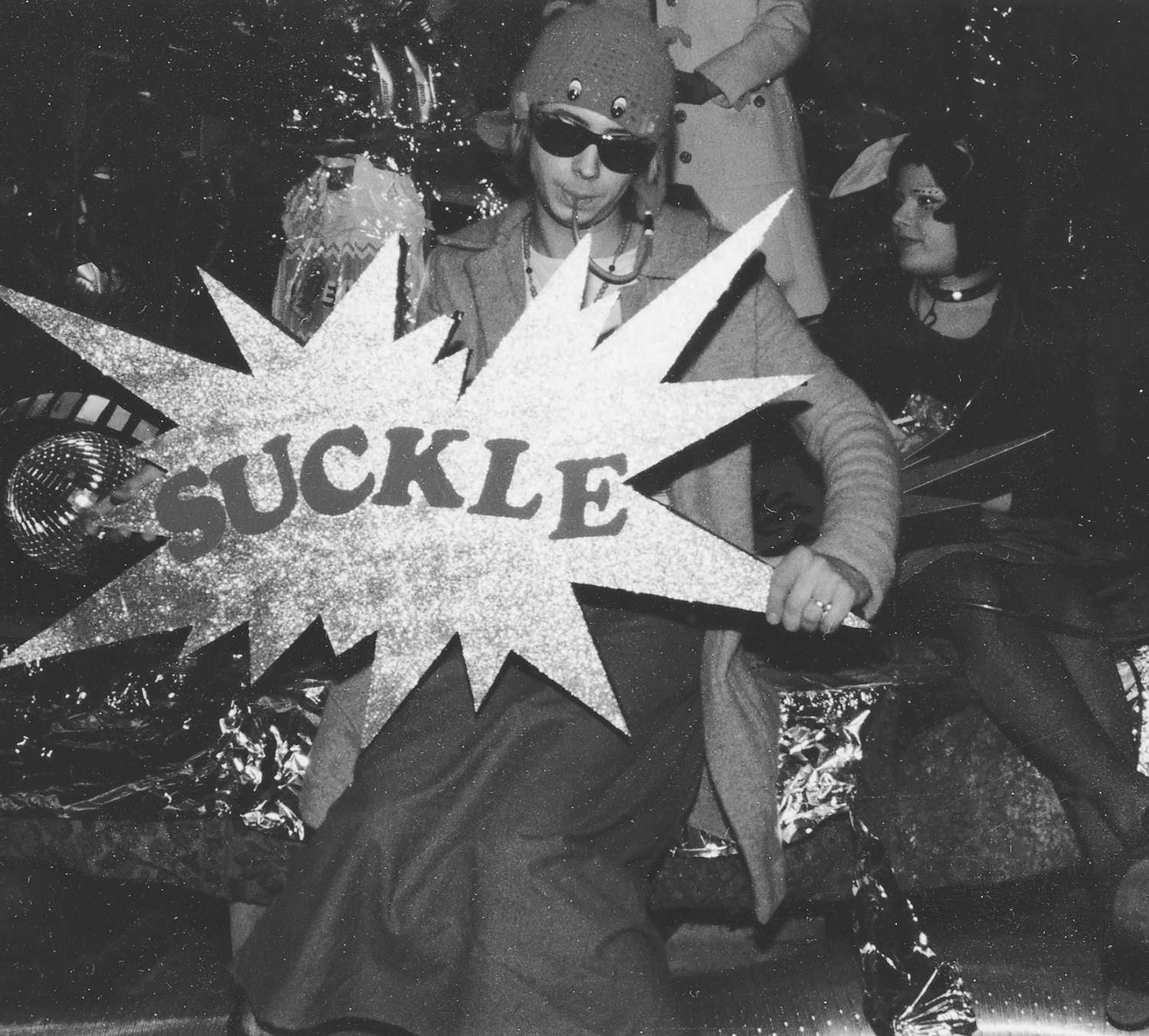

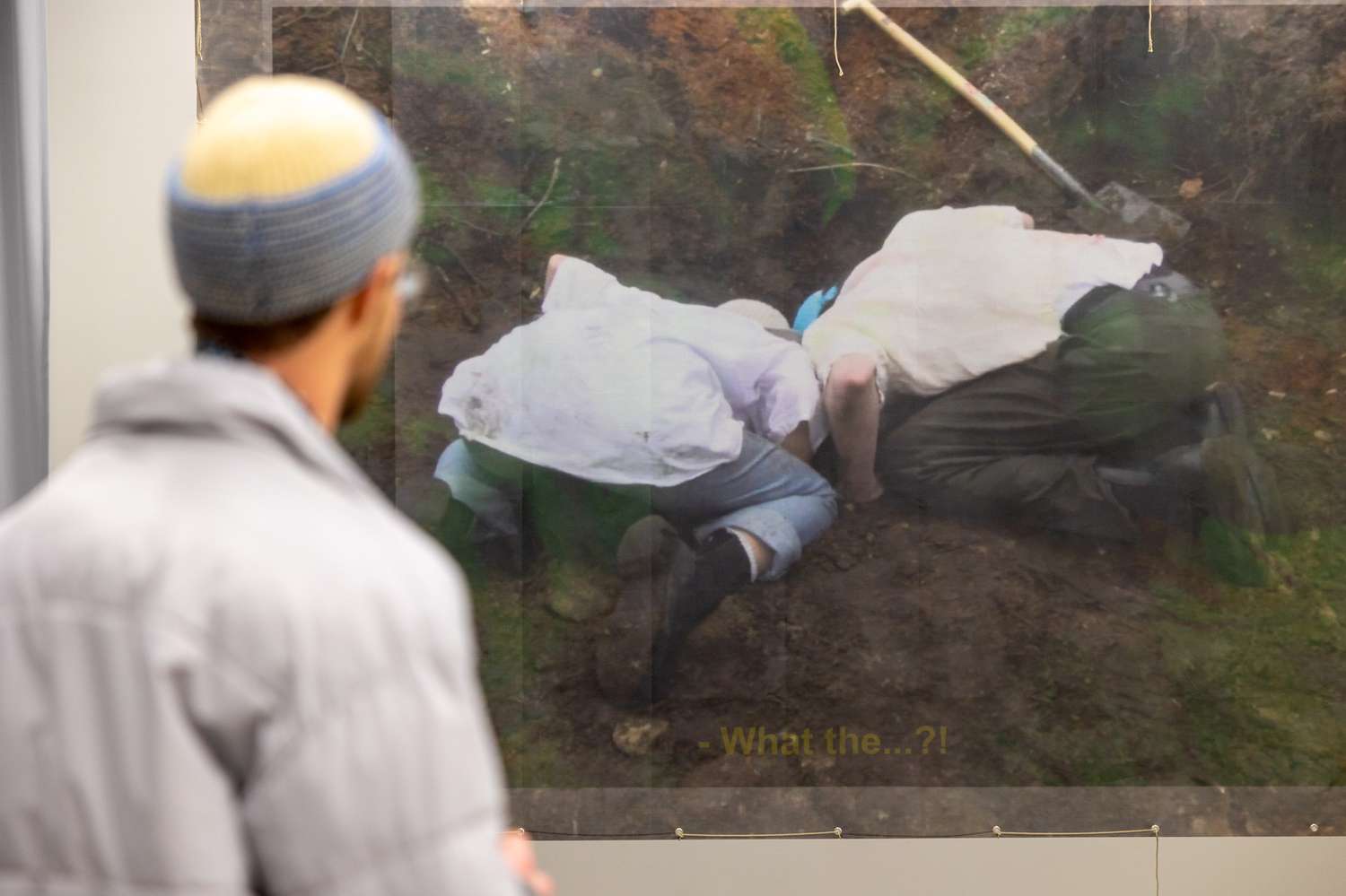

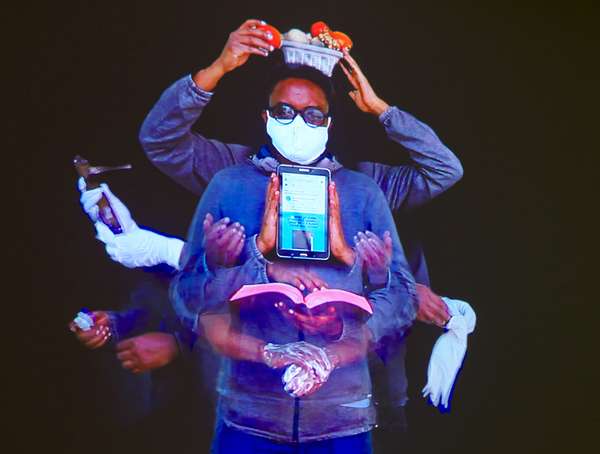

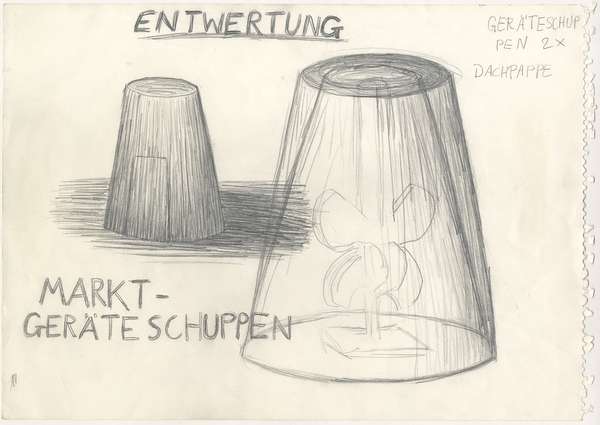

Melián: Let me take that as an opportunity to talk about Annette Wehrmann (1961-2010), whose works we are presenting in the illustrations in this issue of this Lerchenfeld issue. Based in Hamburg, she studied at the HFBK Hamburg and as an artist she was a past master of the temporary occupation of the public space without having been hired by some public body to do so. With her interventions, she popped up at specific locations and used them to create temporary markings. A prime example would be her 1997 work Flohmarkt/Marktbüro (Flea Market/Market Office) on Fleetinsel in Hamburg in the context of the map is not the territory exhibition. The plaza is located between downtown Hamburg and the working-class district of Neustadt; the City of Hamburg sold it off in the 1990s and it thus became the private property of a real-estate company. On the square, the new owners then erected the four-meter-high sculpture Flor Urbana by Hamburg sculptor Jörn Pfab (1925-1986). For her Flohmarkt/Marktbüro project, Wehrmann enclosed Pfab’s piece in wood the way weather-sensitive sculptures in the public space are shrouded in winter to protect them. For the duration of the exhibition, the wooden pavilion was used as the market office for a public, non-commercial flea market and as a meeting place. With this project, Annette Wehrmann succeeded in turning a space where there are no longer any places for people to tarry unless they wish to buy something into an at least temporary venue for the public to use. And by shrouding a Drop Sculpture intended to enhance the no longer public plaza in cultural and decorative terms, at the same time she directed our attention to the artwork, to its function in relation to the square’s history. Wehrmann’s cone-shaped envelope for Flor Urbana remains inscribed in the memory of the city as the invisible marking of the privatized urban square.

Sternfeld: And this is the very sense in which we want our conference to be an assembly. The contributions chosen for this magazine constitute artistic and scholarly research and strategies that create places of remembrance and explore them, but which also take issue with the exclusions and implicit history of violence innate in hegemonic forms of remembrance. They consider remembrance as something we need to fight over, take a stance, underscore what has happened, and look for new spaces to negotiate what this means for the present day.

Michaela Melián is Professor of Time-based Media, and Dr. Nora Sternfeld is Professor of Art Education at HFBK Hamburg.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Long days, lots to do

Long days, lots to do

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

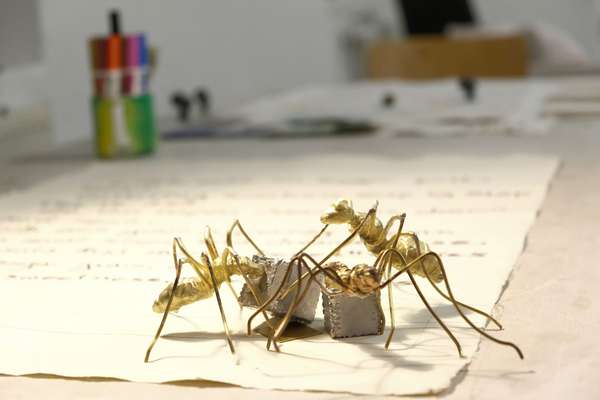

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

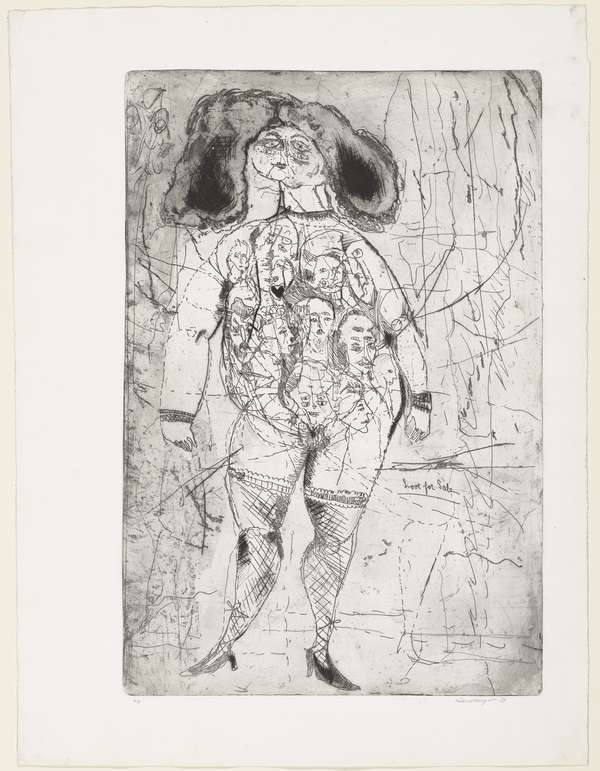

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

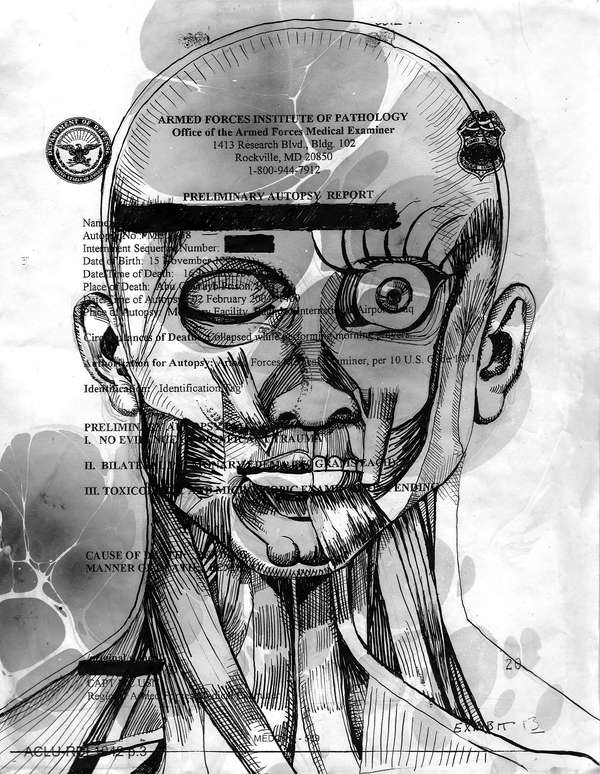

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

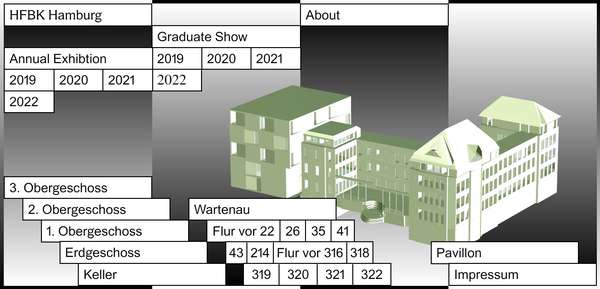

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

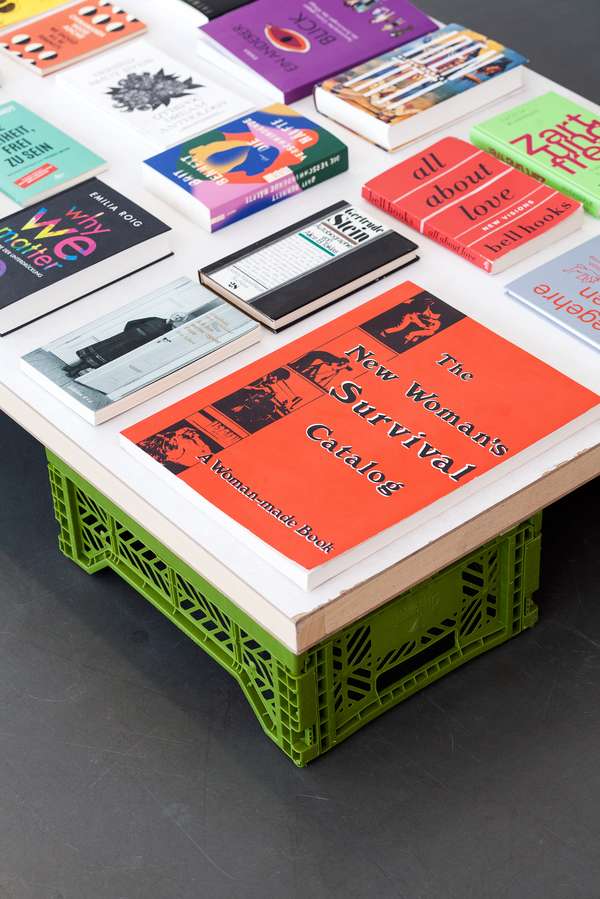

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

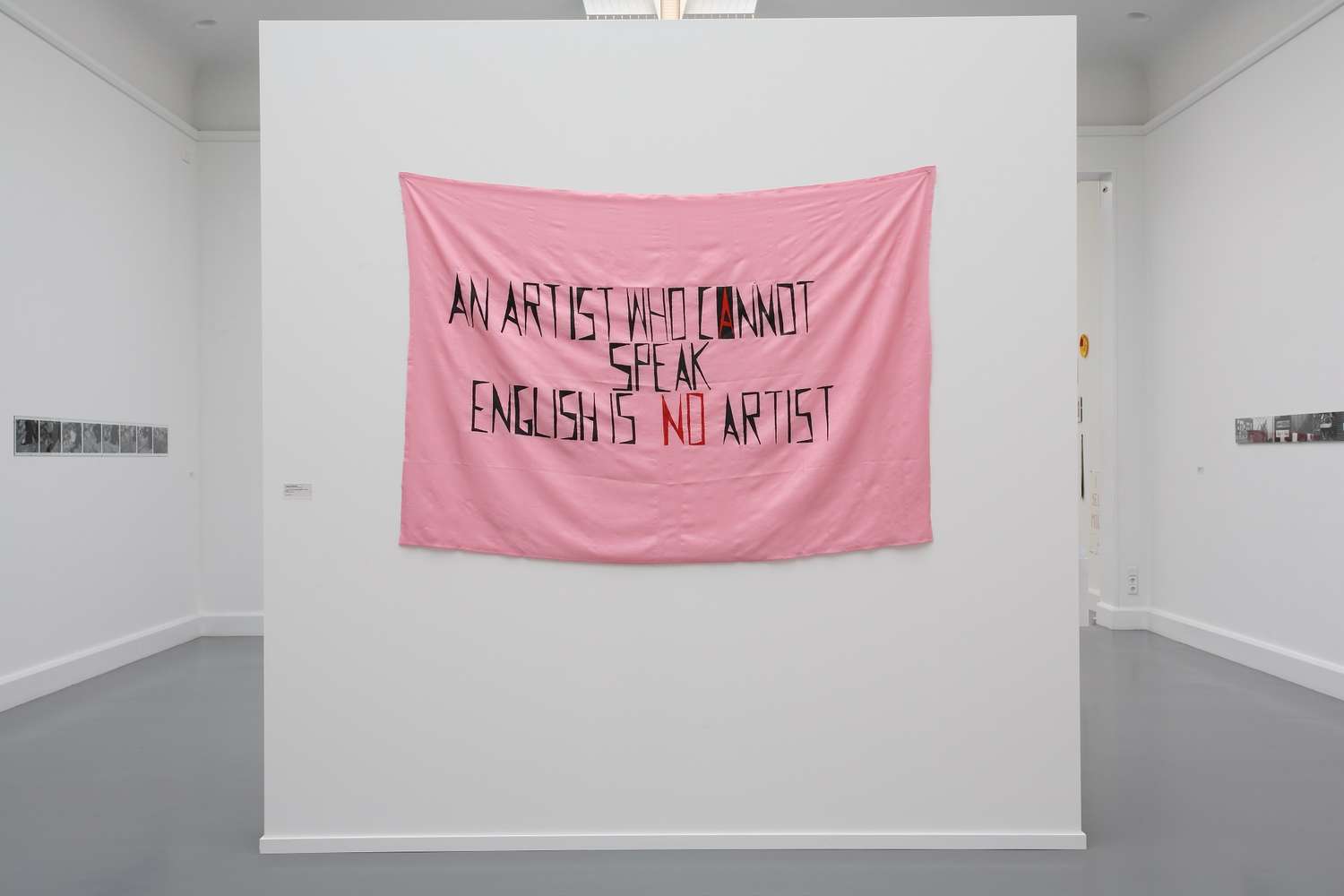

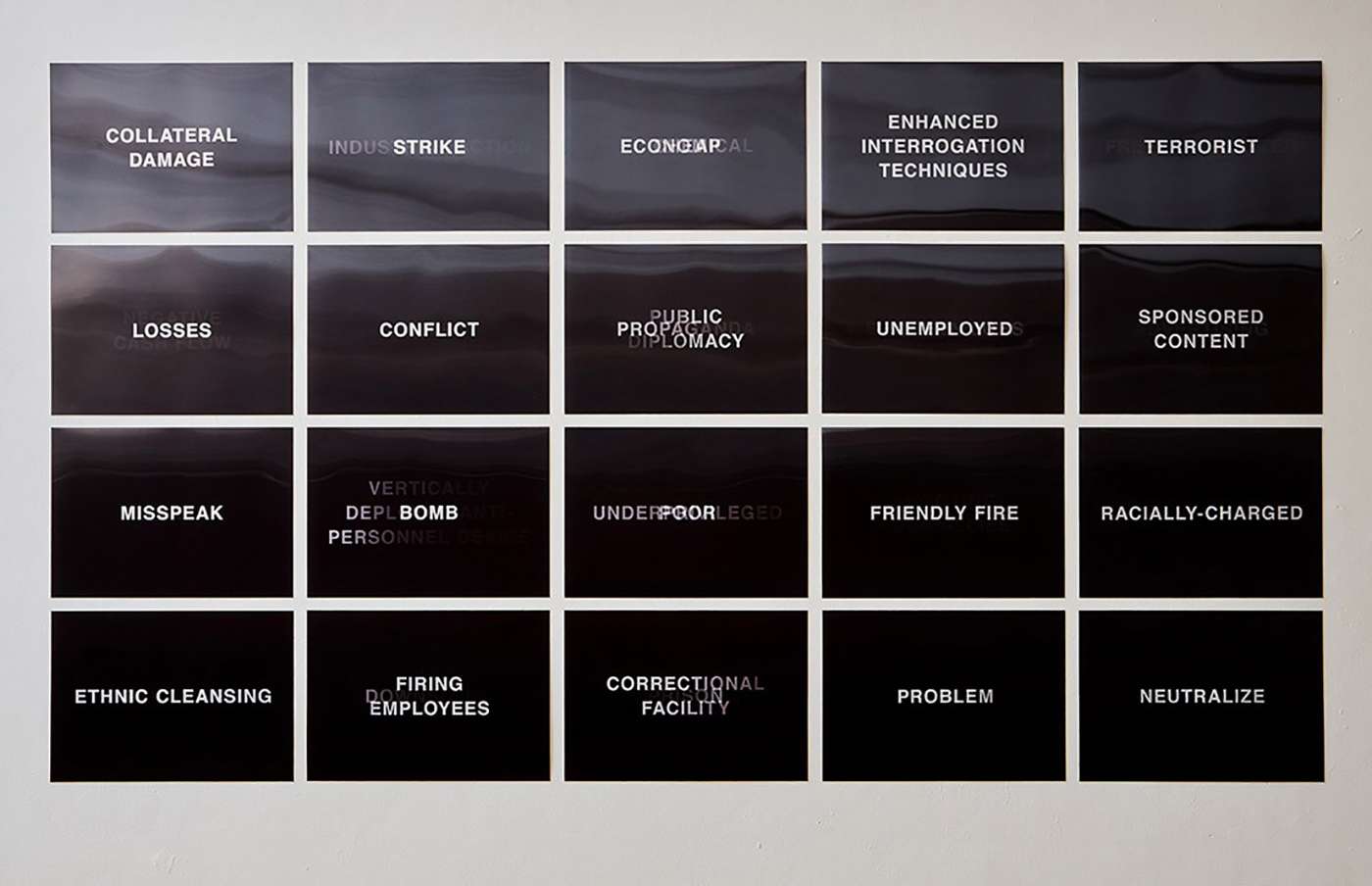

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

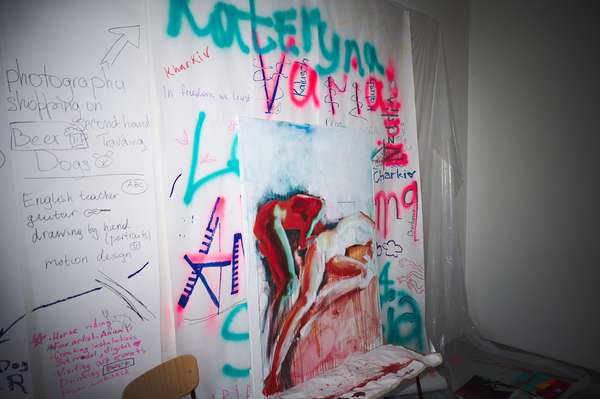

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

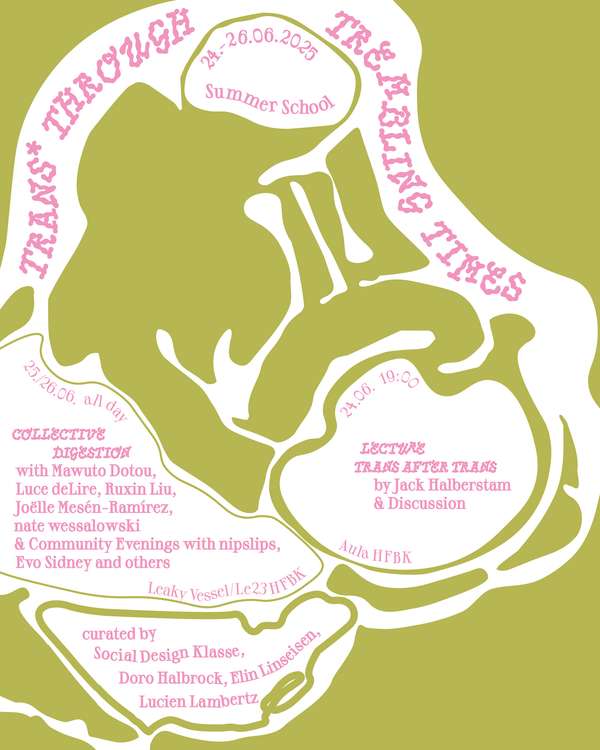

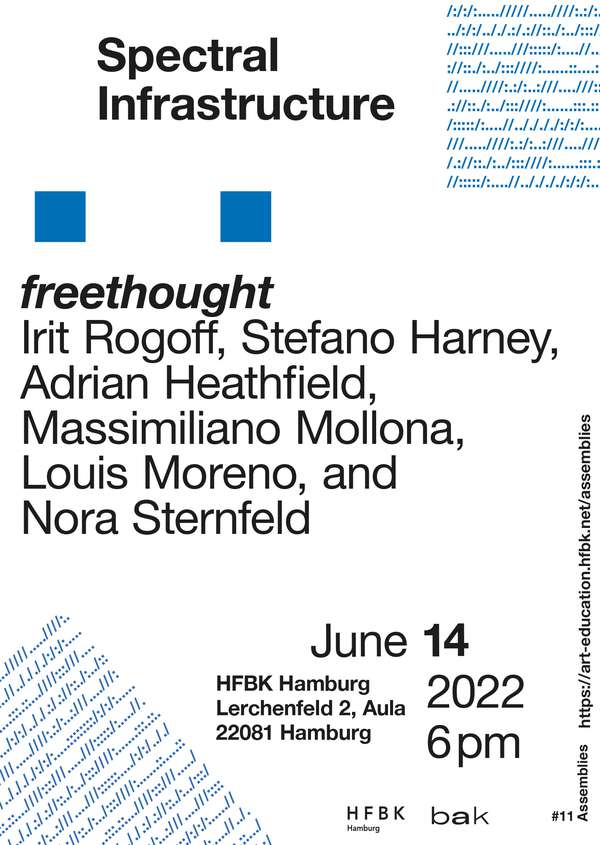

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

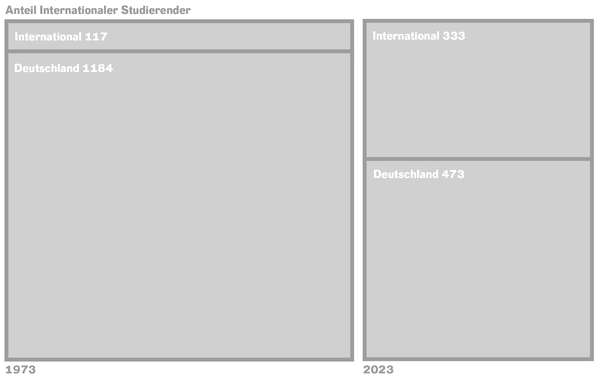

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

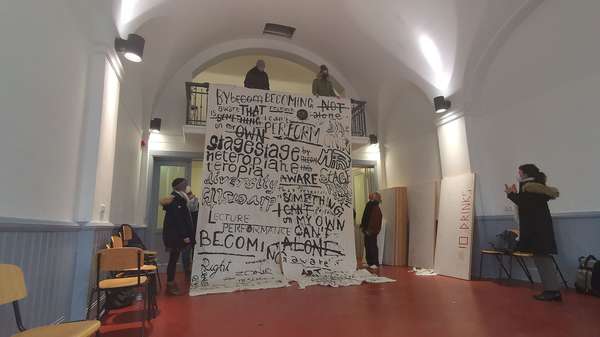

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

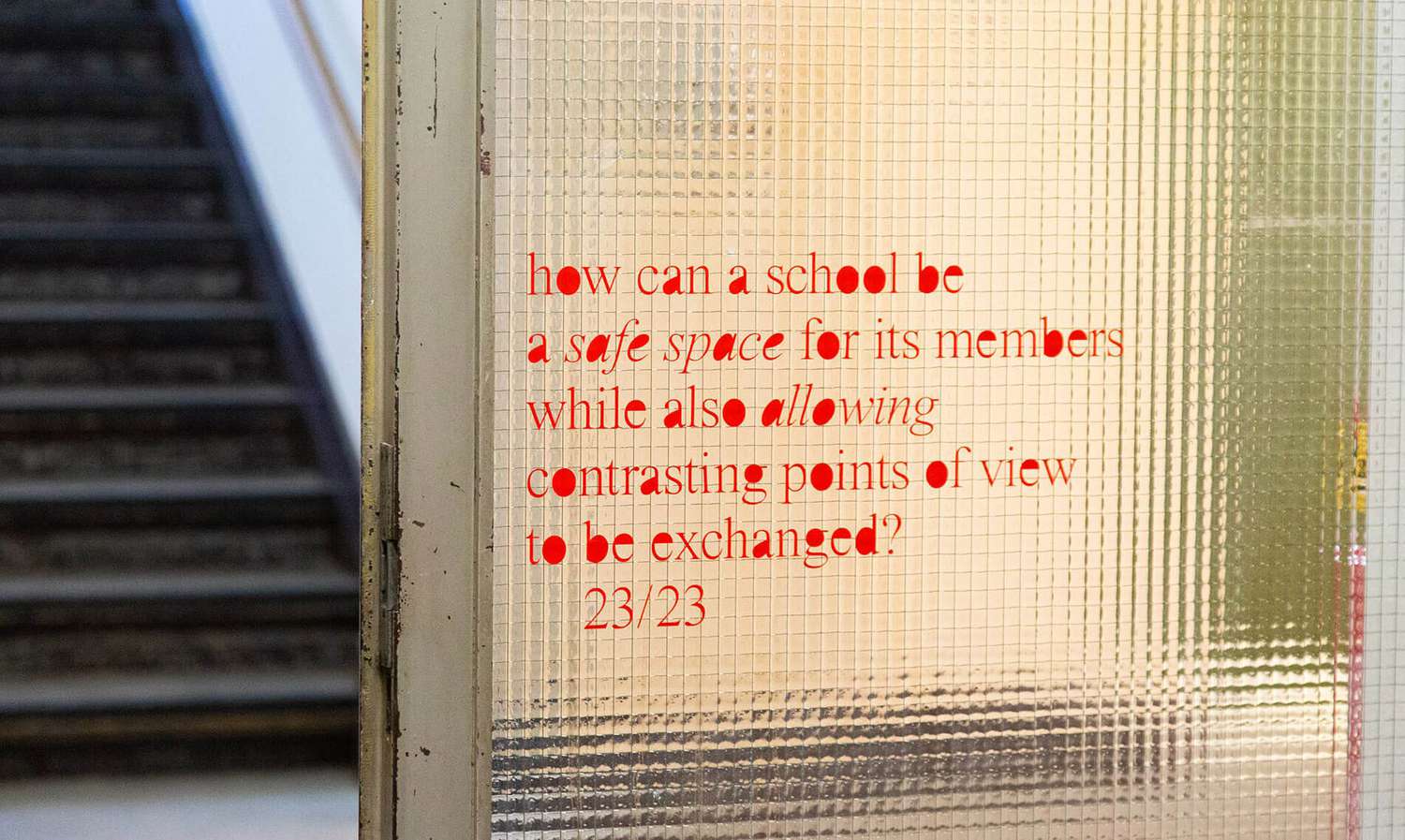

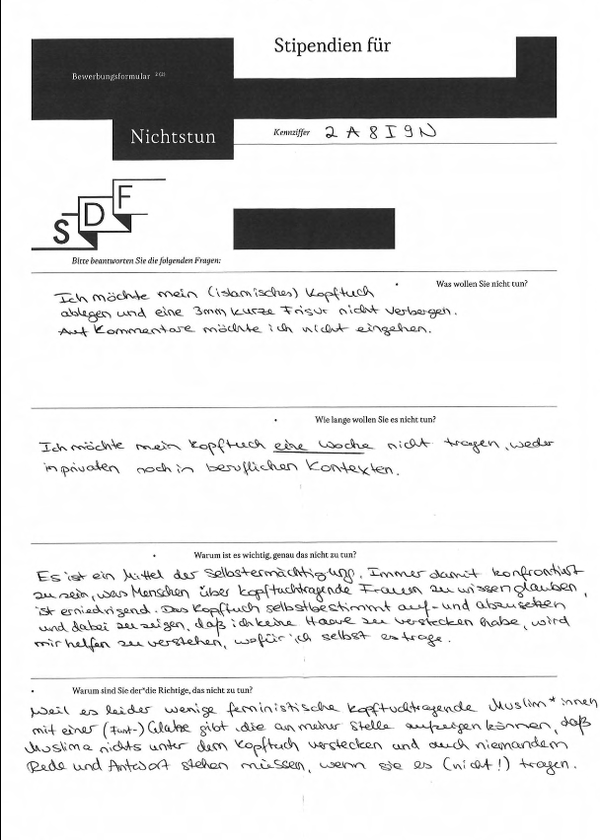

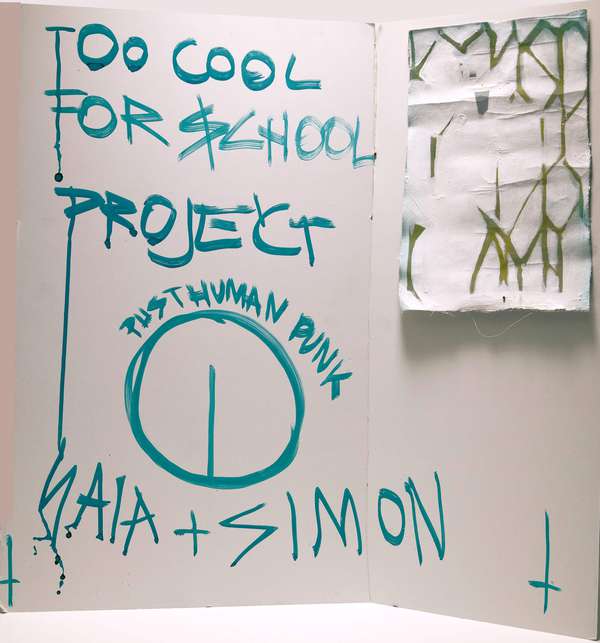

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

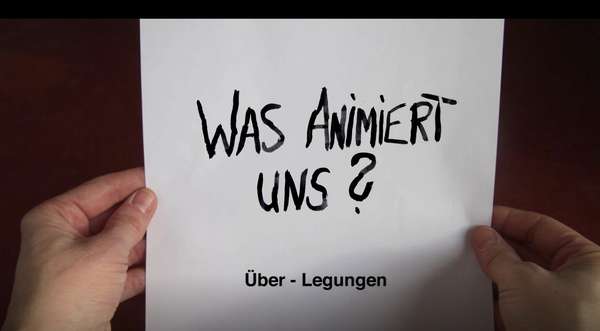

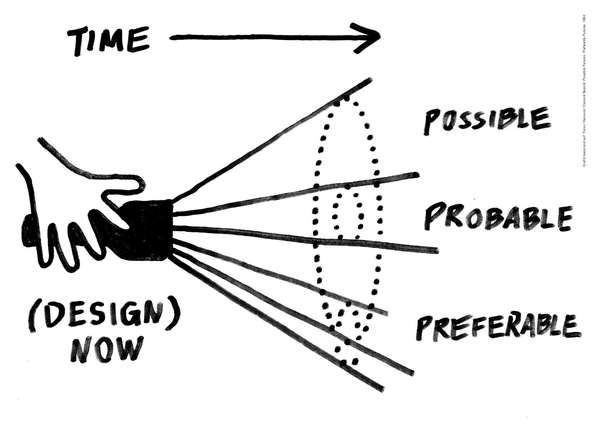

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?