What do you actually do? – Niclas Riepshoff

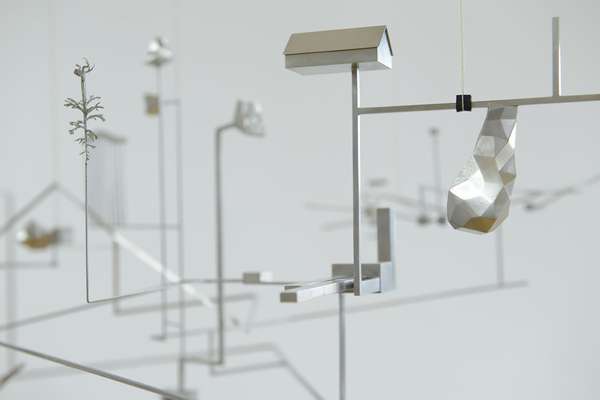

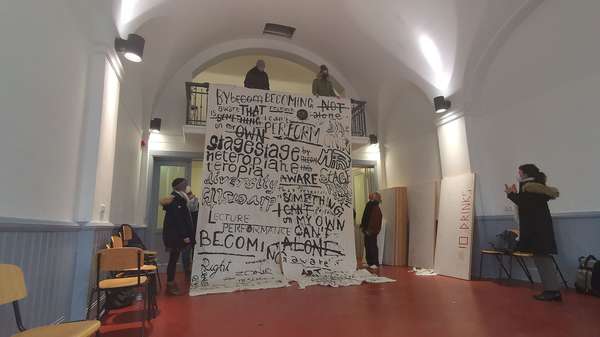

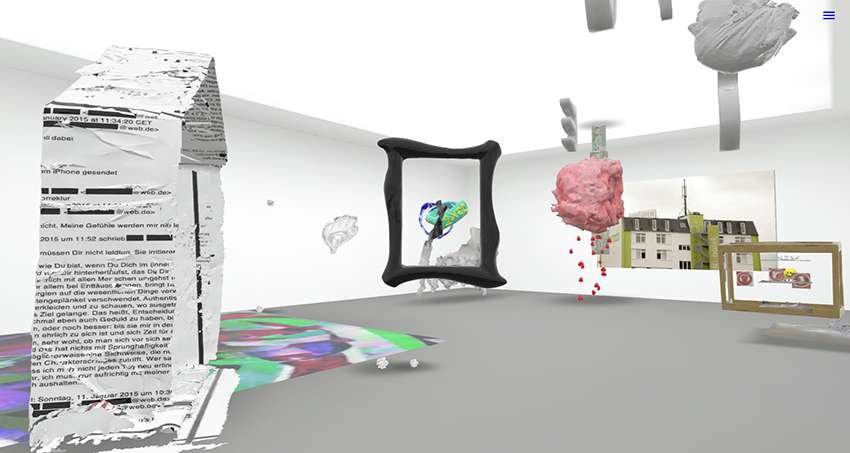

Niclas Riepshoff may have only moved from Hamburg to Berlin last summer, but it’s clear that he’s settled in just fine. Not only has he found a place to live — a spacious two-room apartment in Kreuzberg that doubles as a studio — but he also had his first solo exhibition in the city earlier this year at Stadium, a small project space on Potsdamer Straße with a reputation for presenting emerging artists. When we meet, the show is closed due to Covid-19 restrictions, so instead Riepshoff and I sit together, coffee in hand, flicking through pictures on his laptop. Taking its name from Die Zweite Hand, a defunct listings newspaper that used to be produced where Stadium is now located, the exhibition brought history to life through a series of site-specific, wall-based panels, which combined old pages of the Die Zweite Hand with blinking LEDs. “The lights were connected with a mini-computer so they would light up in different rhythms,” the artist explains. “I wanted it to look like information, coming in and coming out — that the lights were somehow embedded in or connected to something outside room.”

This interest in communication, between works, eras, people, and places, is a recurring theme in Riepshoff’s predominately sculptural output. For his BA graduate exhibition at the HFBK University of Fine Arts in Hamburg, for instance, the artist remade two Jugendstil sculptures that stand in front of the university’s grand entrance in papier-mâché (This is How we Stand, 2017). In the hands of another artist, this might seem somewhat hubristic, but there’s a lightness to Riepshoff’s intervention that comes from the straightforwardness of his approach and his tendency to work with materials more closely associated with crafts than fine arts. “I'm often starting from the point of asking myself: Where am I right now? What information is around me? What resources can I use?” he explains. “I often see something that I then try to repeat, and through this repetition it inevitably transforms into something else.”

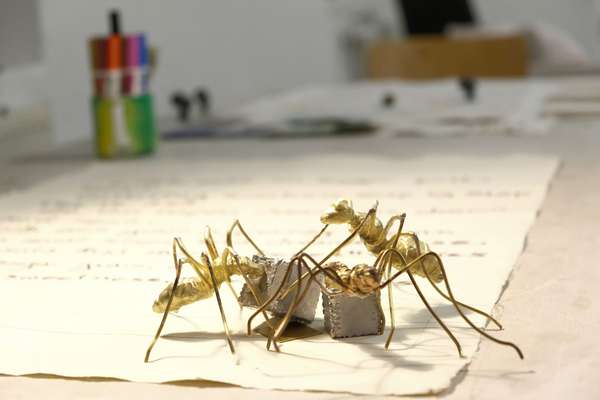

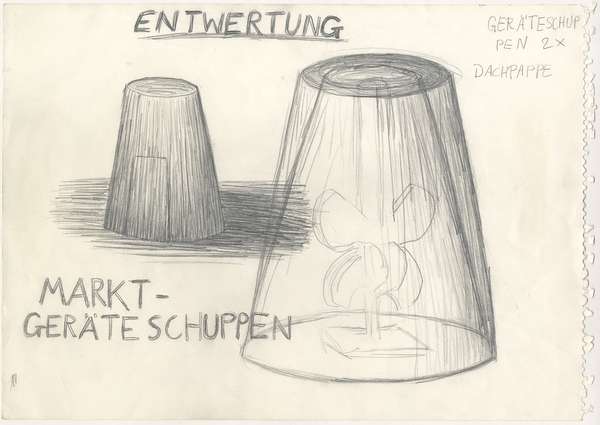

Such an approach was also reflected in Riepshoff’s second solo exhibition of the year, which took place at the Hamburg gallery 14 a. Titled Berliner Öfen (Berliner ovens), the show featured a series of small replicas of traditional ceramic coal-burning ovens (in German Kachelofen). Before the invention of furnaces and central heating, these ovens were the only source of warmth in apartments throughout Central and Eastern Europe. Riepshoff got the idea for the sculptures, he tells me, from his own apartment search in Berlin, where 30,000 estimated apartments are still heated with Kachelöfen, as well as a prior experience in the city. “I was visiting my friend in Schöneberg when he said, ‘Wait a second I have to make it warm here,’ and started shoveling coals into his oven,” Riepshoff remembers. “It was like two parallel worlds: he has a super fancy computer and then this really old-fashioned way of staying warm.” Although it might seem strange, there is also a practical reason for not opting or asking for an upgrade: “When you have one of these ovens your rent is much cheaper,” the artist explains. “Taking them out can give your landlord an excuse to raise the rent.”

For the exhibition, Riepshoff drastically reduced the size of these “massive interior objects” to create “small, kind of cute sculptures” with built-in heating systems that made them hot to the touch. Playing with scale and adding “live” elements, like heating, are techniques Riepshoff frequently employs. Alongside the LED works at Stadium, for example, the artist also included two over two-meter high Papier-mâché replicas of E.T.’s glowing finger. Riepshoff brought in this external reference, he tells me, to avoid the exhibition becoming “too hermetic,” but it was also a way to encourage visitors to have a physical response to his sculptures — something that might be missing in their day-to-day art viewing experiences.

“We're very much limited to tiny squares—well maybe not limited, but we often agree on experiencing art in that digital way,” he says. “When I make work, I want to escape that sphere, even if just to have a different experience within my day.”

The desire to disrupt static viewing experiences is extended through the sculptures’ live elements, which, in addition to heat, have also included light and sound. “I always tend make something that is not really captured in the documentation of the artwork, to have one layer that is inaccessible through the circulation of the work online,” Riepshoff says. “For ‘Berliner Öfen,’ the tactility provides that layer. You are supposed to touch the sculptures and get a warm sensation that produces different bodily reactions and triggers emotions.”

Given this focus on tactility, it seems especially cruel that both of Riepshoff’s exhibitions had to close early due to social distancing restrictions. But after a busy year, the artist has wisely used the downtime as a chance to regroup and think about new projects. “In the beginning of lockdown, I thought I was going to get everything done,” he says with a smile, “then I decided to embrace not doing anything because when does that ever happen?”

Niclas Riepshoff is an artist based in Berlin. He studied at the HFBK from 2013-17 and 2018-19 with Andreas Slominski and Jutta Koether.

HFBK graduate Chloe Stead, together with the photographer and also HFBK graduate Jens Franke, met former HFBK students to talk about work, life and art. It is part of a series of interviews for the website of HFBK Hamburg.

What do you actually do? – Mirjam Thomann

What do you actually do? – Mirjam Thomann

What do you actually do? – Monika Grzymala

What do you actually do? – Monika Grzymala

What do you actually do? – Mads Lindberg

What do you actually do? – Mads Lindberg

What do you actually do? – Astrid Kajsa Nylander

What do you actually do? – Astrid Kajsa Nylander

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

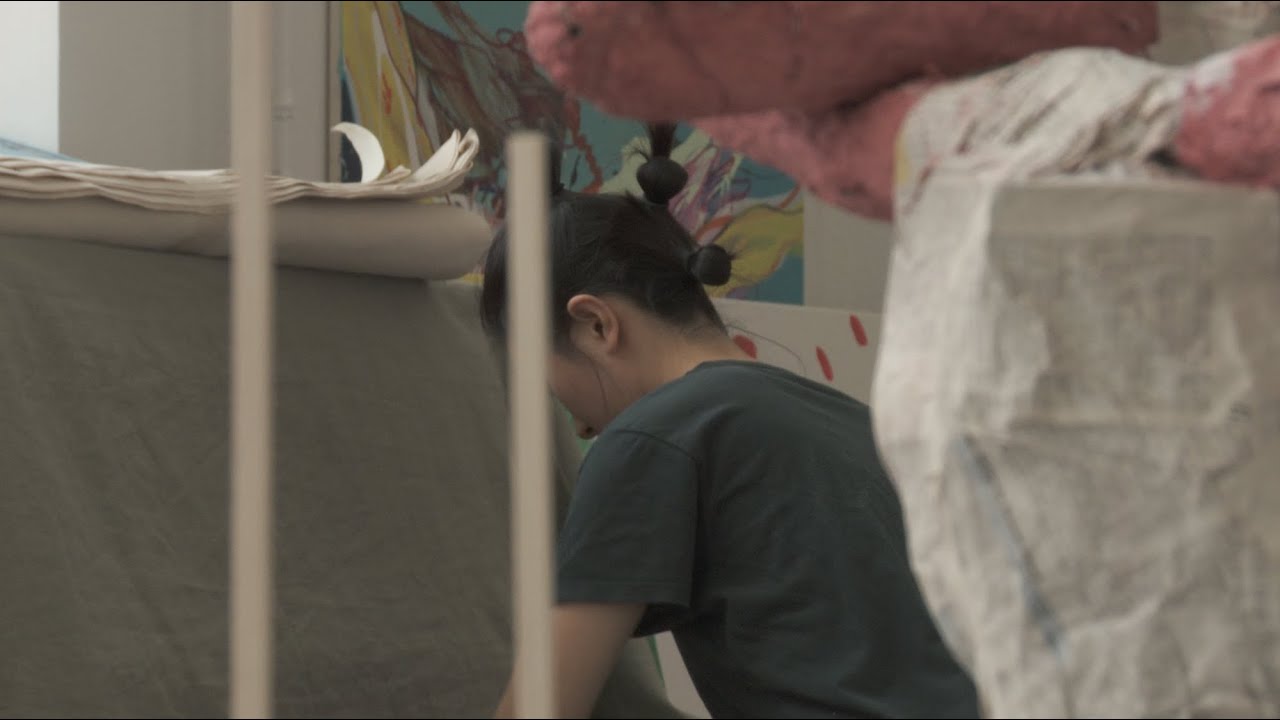

Long days, lots to do

Long days, lots to do

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

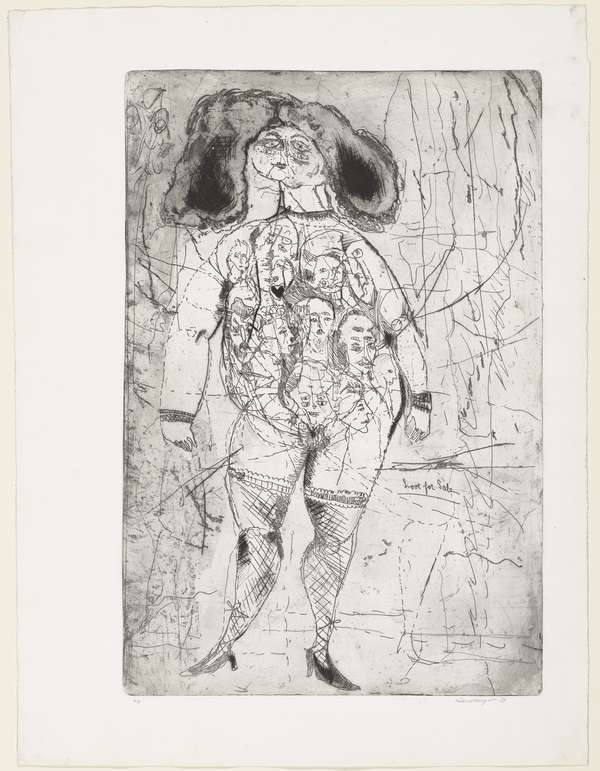

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

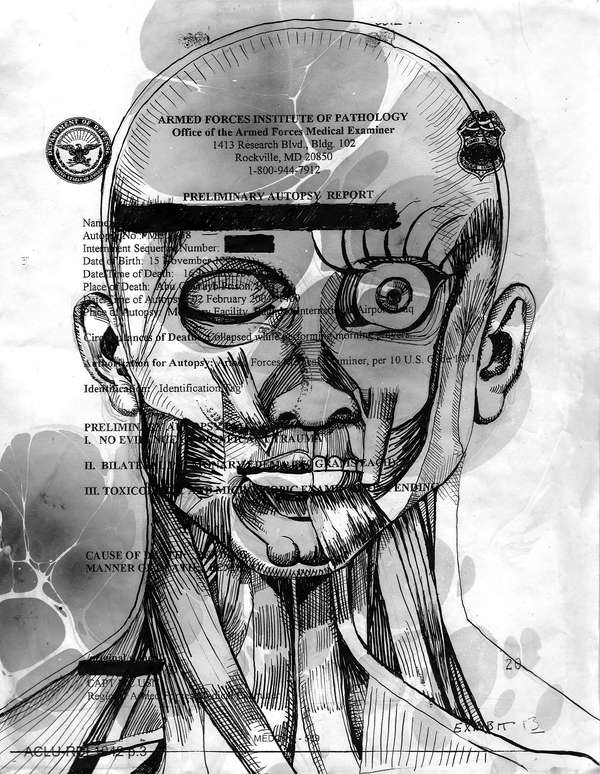

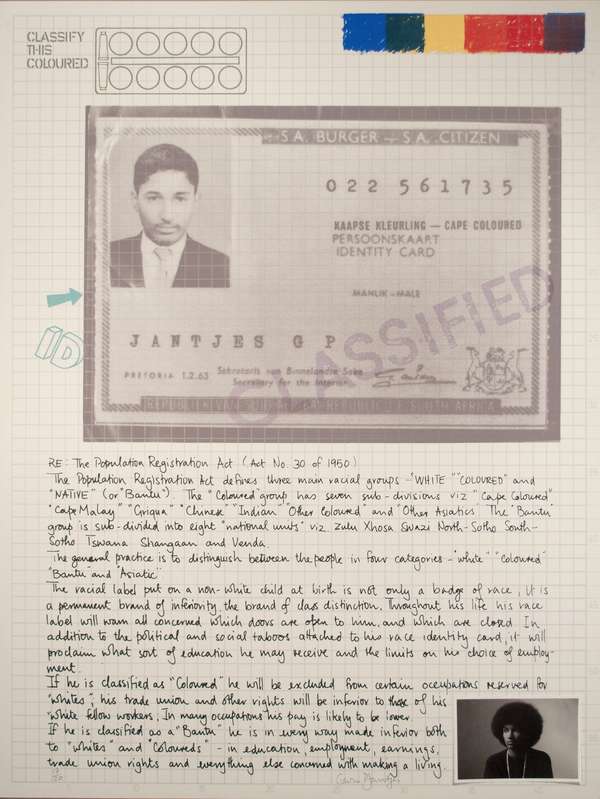

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

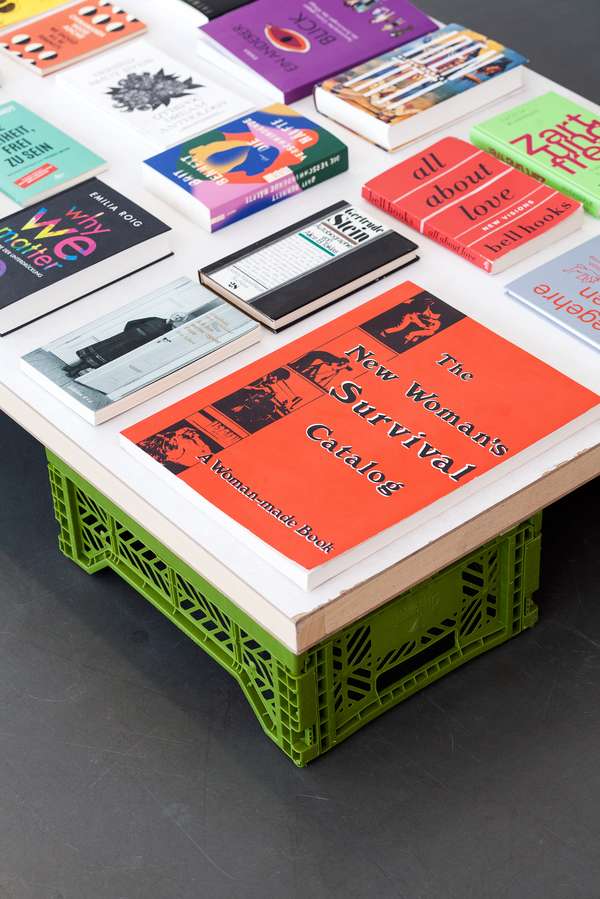

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

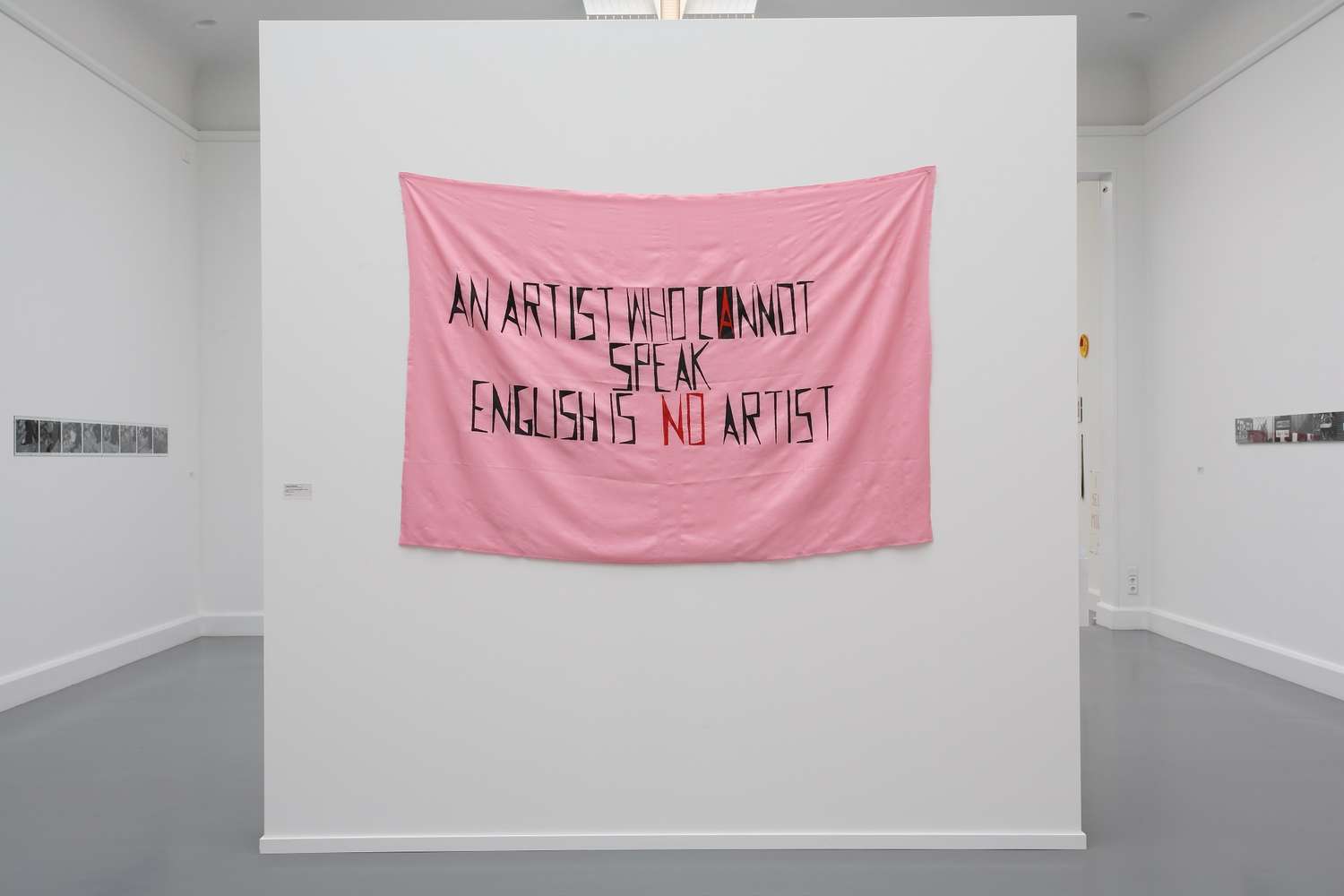

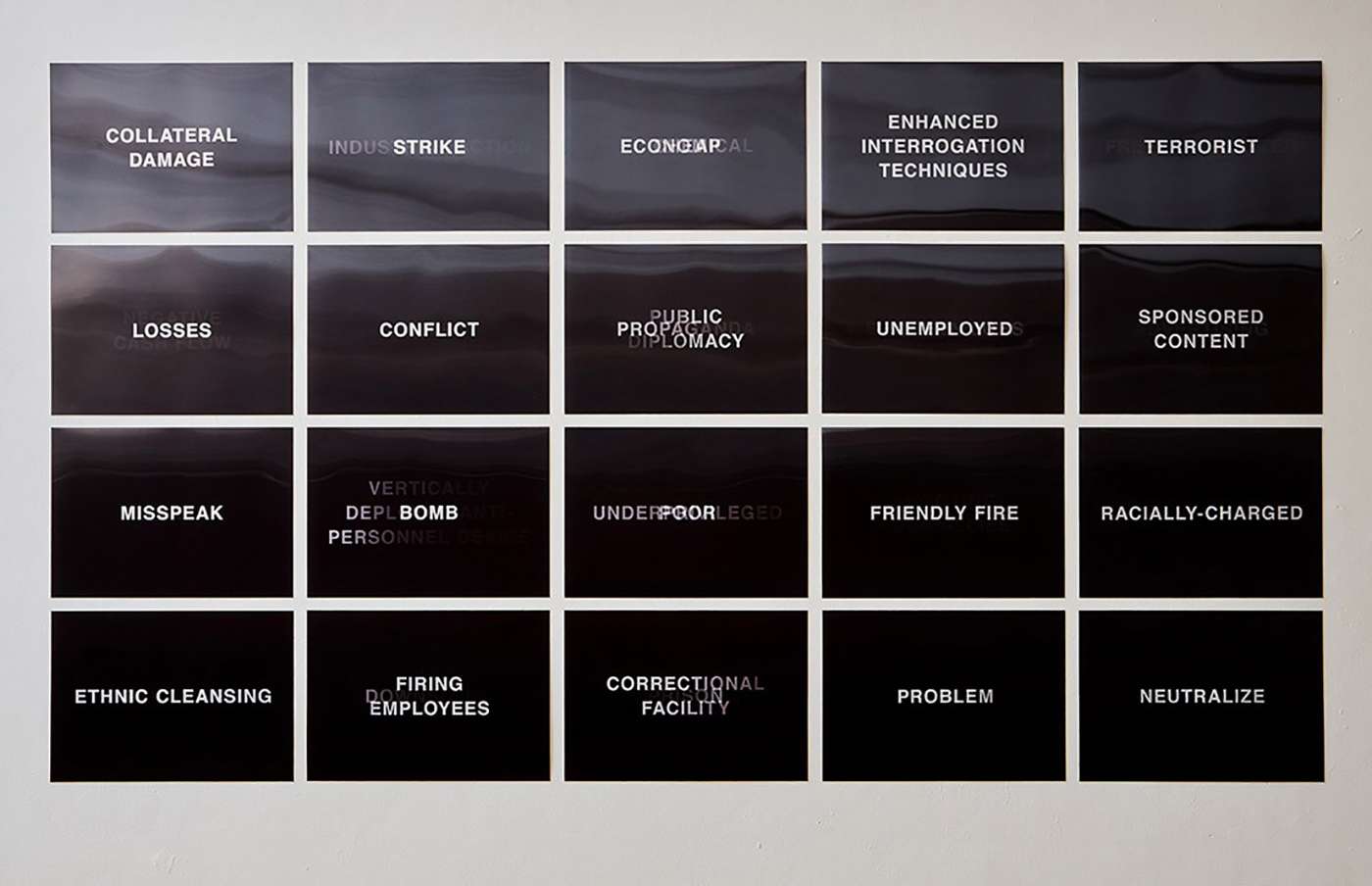

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

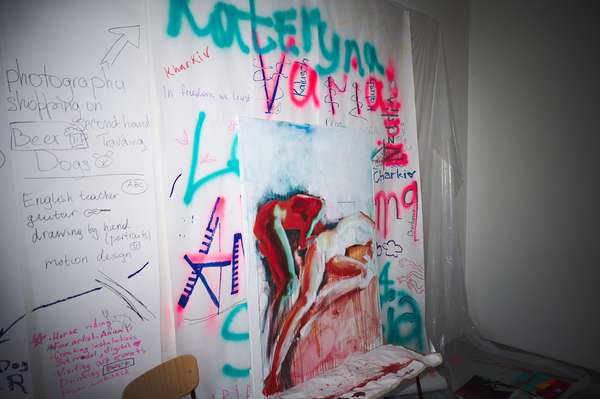

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

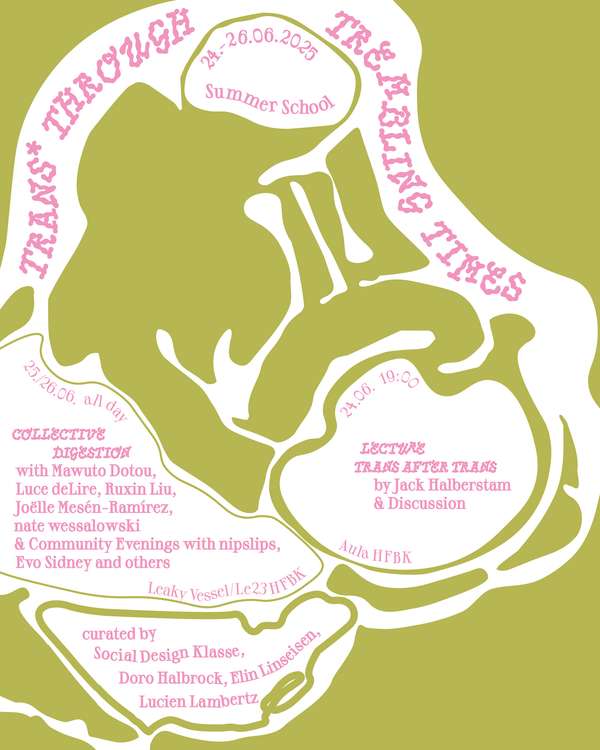

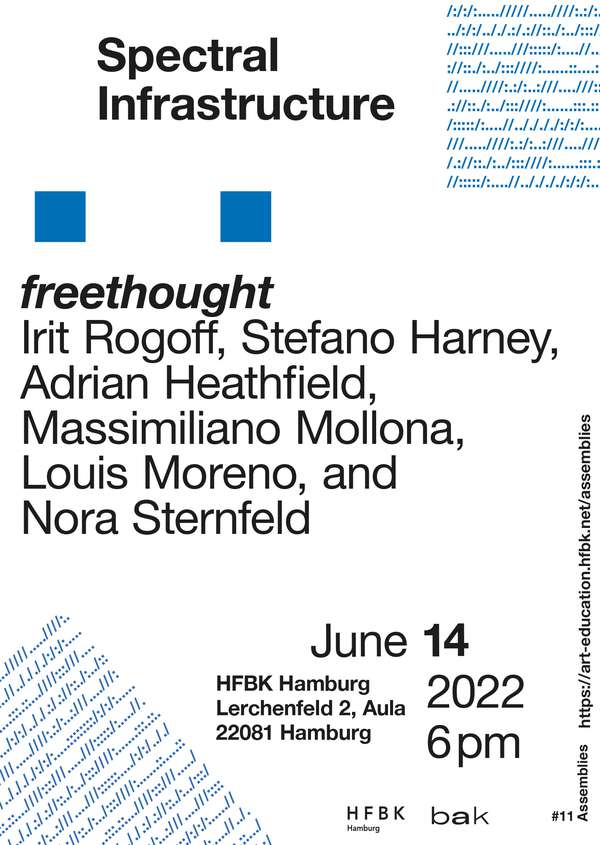

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

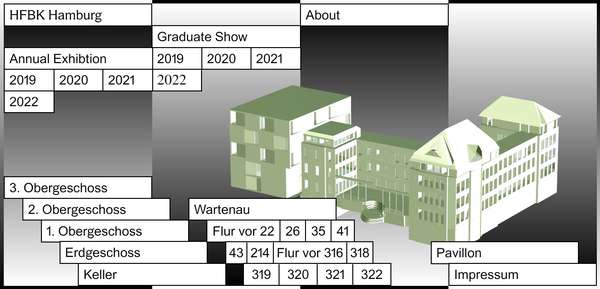

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

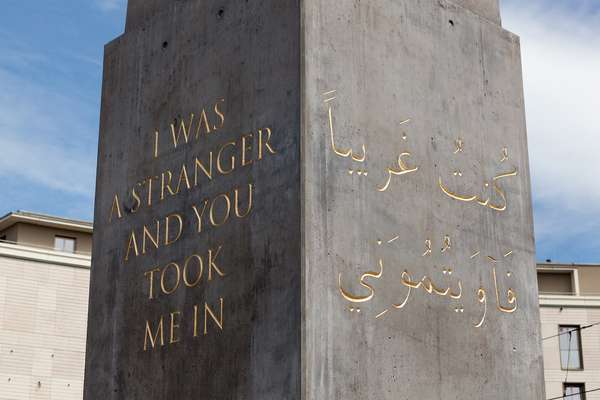

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

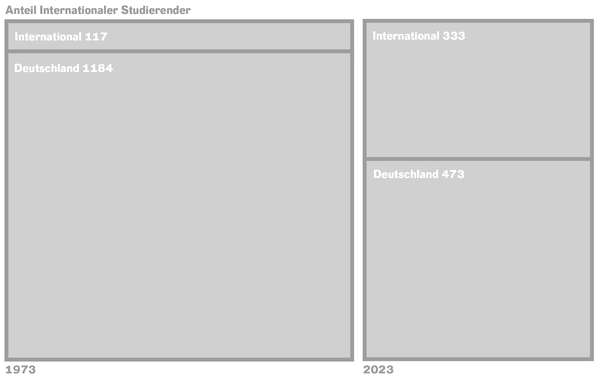

Diversity

Diversity

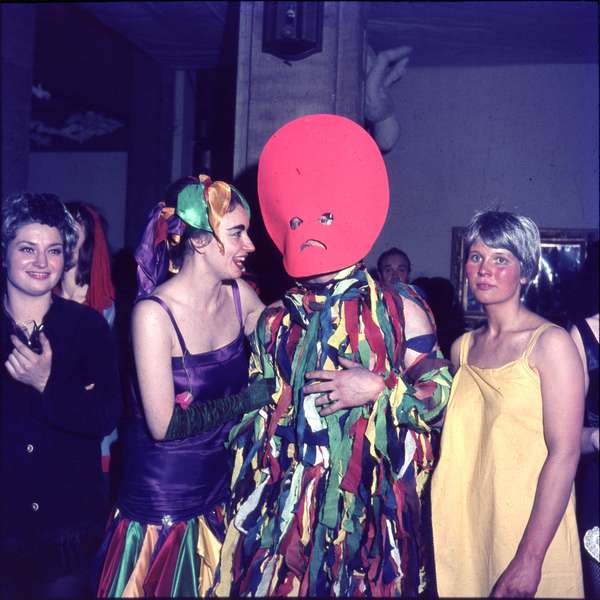

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

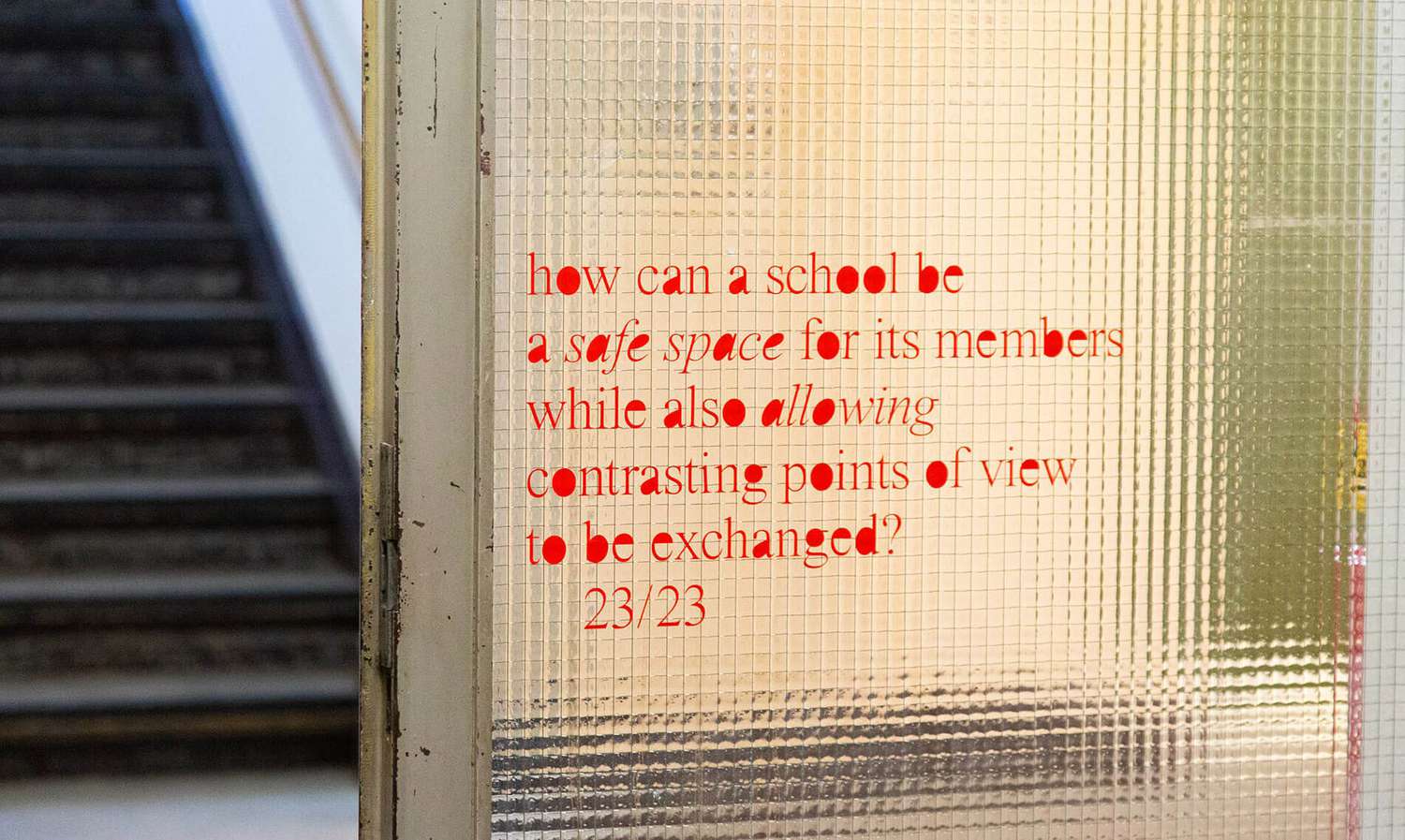

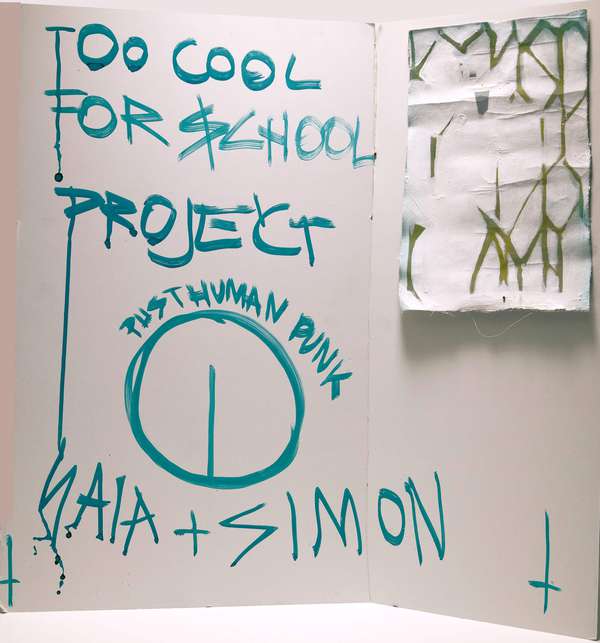

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

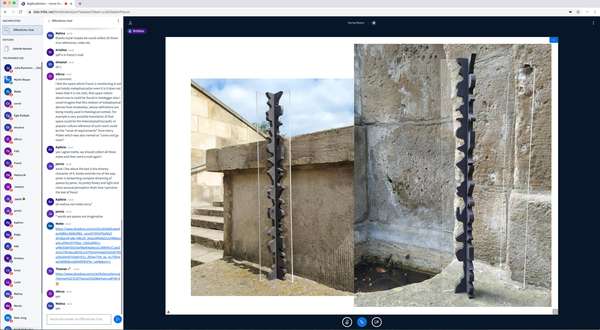

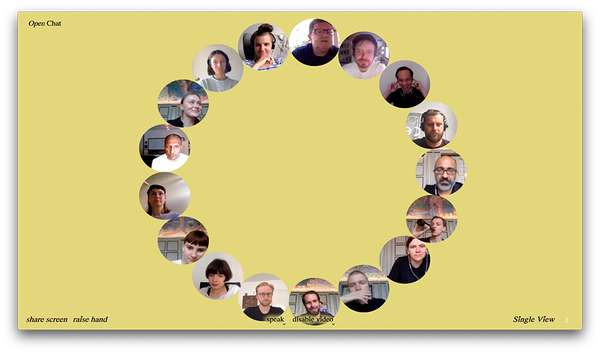

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

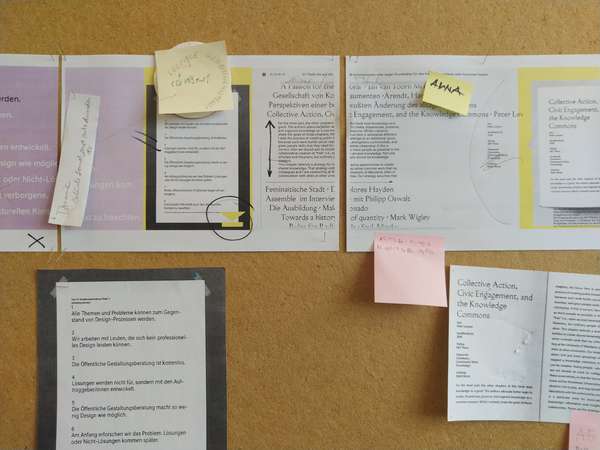

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?