It's an Infrastructure Game

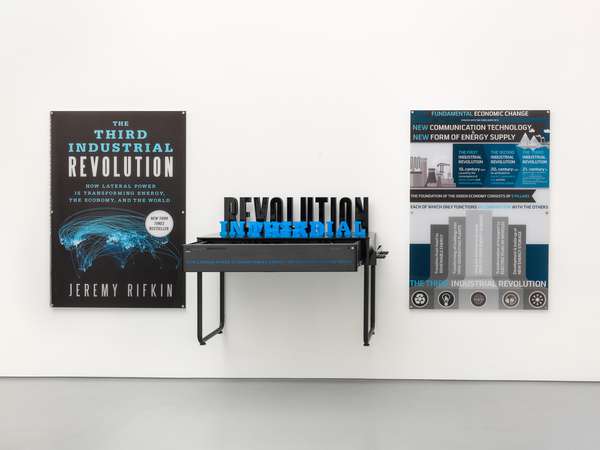

[Simon Denny] Maybe we should start by talking a little bit about what’s in the book. I guess one of the key questions is: What is value in the crypto space? Where does value come from? And this refers both to cryptocurrency, which predates the art, and to this new value that is forming around the distribution of artworks.

[Kolja Reichert] That’s the core question that drove the book. Auction results like a Beeple video going from 60,000 to 6.6 million dollars in three months—that was a shift that was not only economic, it was cultural. I was a late discoverer of NFTs. It was in the wake of the GameStop hype, when for 24 hours an online coordinated gang of young, in some cases impoverished Generation Z people looked like they were able to take Wall Street down, fighting big hedge funds betting against a company they love, GameStop, a gaming company. That also looked like a cultural shift, and that’s where I started becoming interested. These weird values in money, for one thing, of course are part of a very speculative economy, but they wouldn’t exist without another very speculative economy, which is cultural value, people gathering around certain values, assets, conversations, and agreeing on the value of them. And when I got more into it, it seemed like suddenly there was a solution to a really fundamental question I had long been interested in: How can you translate cultural value into financial value?

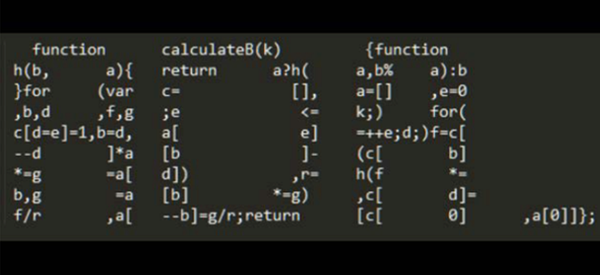

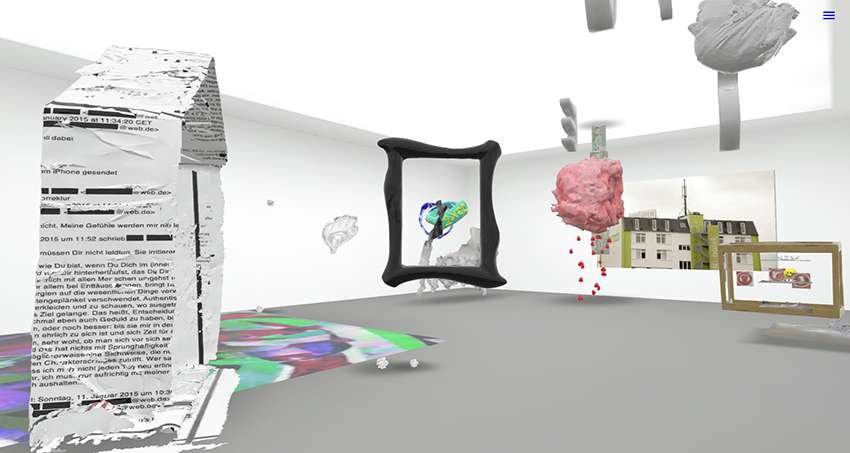

[SD] Maybe it’s worth defining some terms we’re talking about. I think there are a lot of different ways in which artists use cryptocurrencies. I think the most famous way now is by selling JPEGs that are linked to assets, a kind of registry. For those who are new to NFTs: the basic structure of an NFT, like one of the most well-known works by Beeple, is that it’s a digital file which is an artwork. It is then registered in a blockchain, which is basically just an online database of transactions, which tells you who owns it. So, it’s a very simple thing in some ways, what an NFT is.

[KR] You just explained blockchains and NFTs in one sentence.

[SD] Yes, and it’s often worth saying, it feels more complicated than it really is. I think everybody who is familiar with an auction house like Grisebach knows about how eccentric things gather value and that trading them, those objects that hold value, also can be an act of care and an act of speculation at the same time. And I think that’s something that is really true with NFTs. In some ways these digital artworks with an online registry that a bunch of people take care of are like something you already know from another context. It’s not so different.

[KR] And it’s surprising that you use the word “care”, because what is visible from the outside is huge prices, and everybody thinks, “Speculation! When will the bubble burst?” So where exactly does the care component come in?

[SD] Maybe that’s worth also reflecting on: the idea that people buy artworks because they like them and they see financial value in them. And I think that’s been true of people for my work. They come to an exhibition, they see a nice thing that they think has cultural value, but they also see a price tag and a container for financial value, and they buy that asset so that it holds both their cultural value and their financial value at once. And it’s a nice way to also support the people who made the cultural value, but there are other incentives to put your money there. It’s also kind of a fundraising tool. So, I would say that a lot of NFT buyers come for similar reasons, both for speculation and for cultural value. I’m also an NFT buyer. I have a collection of NFTs. My collection of NFTs is unfortunately more various than my collection of non-digital artworks, which I also like to collect. I have a small art collection as well. But what’s great with NFT collections is that anyone can look at my profile on various platforms and see which things I’ve bought.

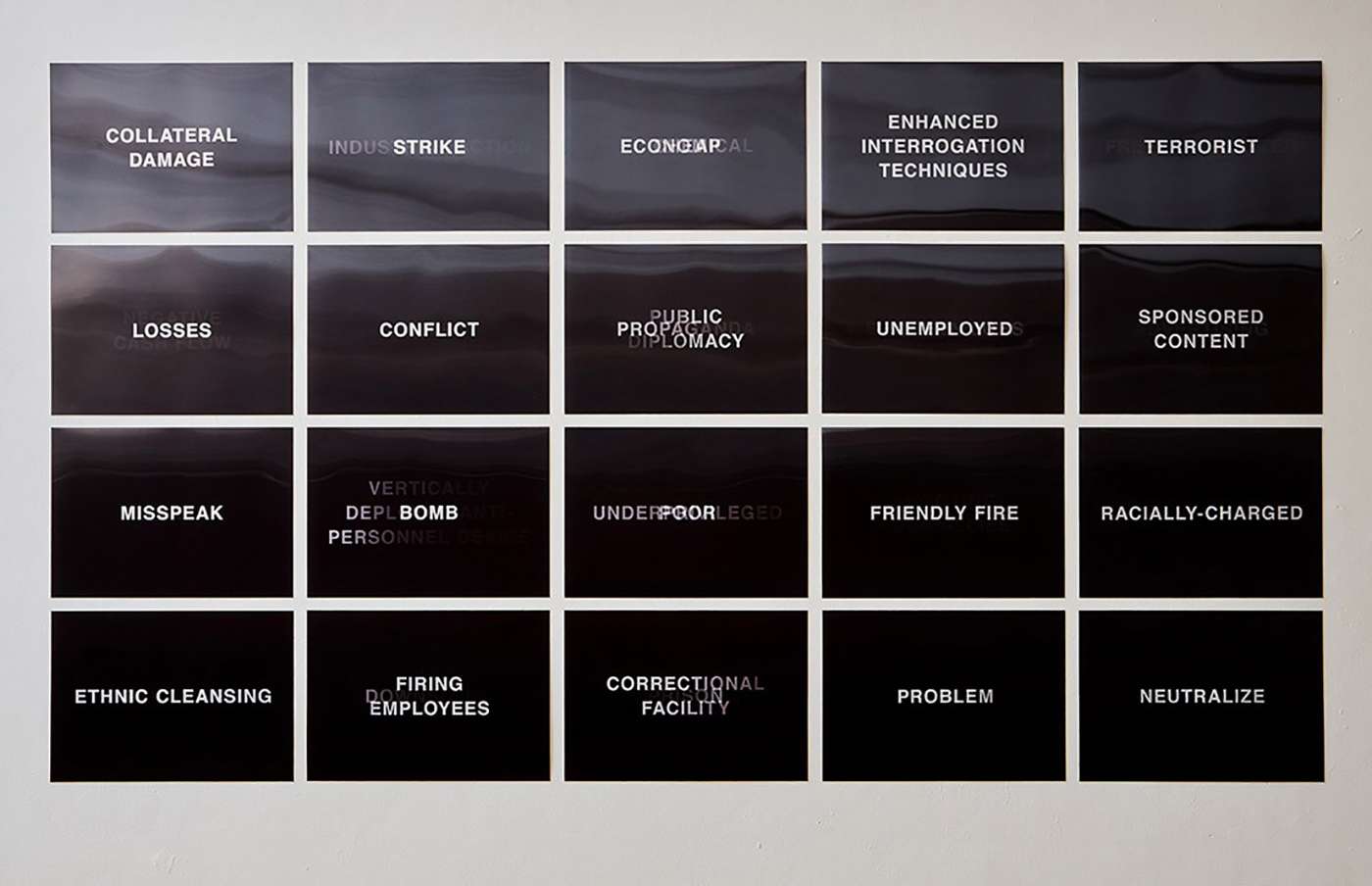

[KR] There’s a lot I still haven’t understood about how value is created. Why does Kevin Abosch sell a super generic, boring digital photo of a red rose for one million dollars, a JPEG that everyone can view anywhere? Compare that to crafting a very considered work about the energy consumption of blockchain mining with a legacy gallery, Petzel in New York, employing all the legacy of critical reference art. You use mining computers you bought on eBay, people buy an animation of these computers, and the moment they buy it and the thing is minted, the computers are taken off the blockchain again and given to Oxford University to serve in climate modeling. It’s beautiful. It’s also like a parody of reference art. Why does this work only gain five-figure results?

[SD] I think we know this type of behavior from the “legacy art world,” which is the term I like to use for the art world that we’re speaking in now. It’s because Kevin’s activities and his artworks that he’s created have a certain audience and a certain visibility within that audience, which cares about and buys those NFTs. It’s the same reason why a Christopher Wool—just as an example—is more expensive than another fantastic artwork by a younger artist or a less visible artist. It’s because within the group of people that buy those assets, there’s a social hierarchy and a kind of critical discursive hierarchy that has built up a certain value around those things. That’s true in NFTs as well, right? And maybe it’s worth stating that at this stage, I think, the people who buy art and the people who buy NFTs are different people, for the most part. That’s also true with my own work. The people who buy my NFTs and the people who buy my sculptures that I show at Buchholz or Petzel are different people, and they’ve created their wealth in different places. They value different things, but they both love the culture that’s produced in these particular formats because they stand for something that they like. [KR] Right, but one culture seems to buy trivial, meaningless JPEGs, and the other audience agrees that Christopher Wool deserves high prices because his work is better. It’s not just the social network that’s better. The artist’s work itself is better. You’re reducing everything to social connections here, and there’s a heavy, heavy provocation in that.

[SD] Well, I think criteria for quality and value and culture are quite difficult to pin down. Let’s just say there are not only differences within one particular market, or one particular series by the great Christopher Wool and the not-so-experienced young artists, which you represent. For example, I grew up in a country, New Zealand, where there were completely different canons vying for what is a valuable cultural object. I grew up in a post-colonial context, for want of a better term, and there was a white art history and an indigenous, multicultural art history at the same time, and they both go to auction and they are both sold within this kind of system. The reason why I bring that up is because I think putting cultural and financial value together is always a challenge, and to say this is quality and this is not is always a bit of a social game about who’s saying what and who has the power to say.

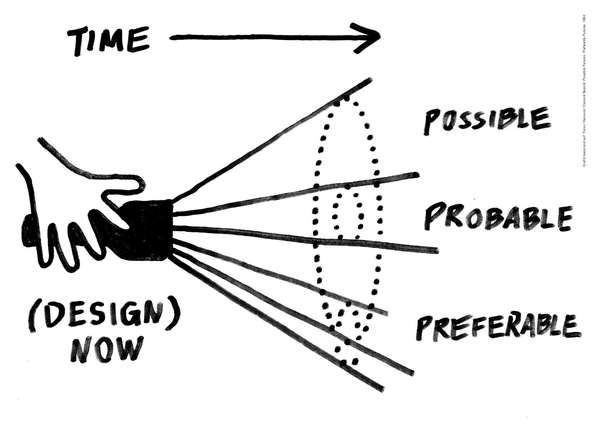

[KR] I don’t want to go too deep into my conception of art criticism, but I think the product that we sell as art critics is not only judgments, and it cannot be objective criteria either, because criteria are always developed by artworks. So, what we can do is compare artworks with artworks, but what we actually do is something more. We create a common ground of reference and put works into a certain narrative. It’s like miners: When an artist tries to add an artwork to the blockchain of human culture, people around the world have to legitimize, verify this transaction before the artwork is added to the chain. Narrative is the product that art critics sell: to show how we can be affected by artworks. What are the causes that this artist is fighting for? What is the happiness that you can get from art? And narrative to me seems also to be the core resource of NFTs in a way. It seems to be a very fictional market, where fiction and finance marry in an extreme way that we haven’t seen before.

[SD] I think one of the reasons why NFTs have attracted so much financial capital is because there was a lot of financial capital to spend for people who very quickly changed their personal financial situation because cryptocurrencies themselves ballooned in value. You don’t have an NFT market without the incredible rise in perceived, stated, and actual value of Bitcoin and Ether. And most of the volume of sales of NFTs is done in Ether and on the Ethereum network, so you also don’t have an NFT market without the growing utility and spread of the Ethereum ecosystem as a whole. I guess also it parallels narratives of an evolving, different web, which needs a financial assets component to it to function in a different way. I think one of the most interesting things about crypto and NFTs is what people call Web3, and changes to the way ownership works on the web.

[KR] Right. I, like many, first looked at this NFT thing like, okay, if I compare these images to the images I know, on my wall or in the galleries I like or in museums, they look bad. So NFTs are bad. Culture is declining because people are losing taste. Then, if you look at these projects, you understand the images are not what is being purchased. They’re just the cover artwork. You don’t buy so much the picture, you buy the social relationship, you buy membership in a network, but you also in a way buy the fact that you’re buying. But in the more interesting cases, you buy building blocks for new ways of organizing.

[SD] The claim by those who are building this new web is that, in a Web3 world, we have a technical way of being able to share a piece of the financial upside of the value we create as users, as a part of the infrastructure, and the fact that we can then own and trade those means that all users can be owners at the same time. It’s not only the overlords of big companies that get benefits in this new web. It’s you and me as well. Not only that, but the social benefits that we create by being social, by interacting with each other, that at the moment only shareholders of Twitter, Facebook, etcetera benefit from financially. If each user can keep a token that carries some of that cultural value that we’re creating ourselves, they can also get the financial value from that percentile. NFTs are maybe a part of that infrastructure. This is like a test case for that environment. As an artist I create buzz around a JPEG, I create a following around a particular group of JPEGs that tell a particular story. People get excited about that, there’s cultural use value in that, but I also get to keep some of the financial value of that behavior around that because that JPEG is linked to a financial store of value that the market value can be expressed in, that is always joined to that JPEG.

[KR] We can also compare it to the art market as we know it. If you make an innovation as a gallerist together with an artist, and you are successful, you have to be super afraid, because with the speed at which prices now rise due to the increased concentration of wealth, the artist has no other choice than to switch to the next bigger gallery that can handle the demand. And if a work goes to auction ten years later, the artist sees the return multiply a hundredfold, without getting anything. There was a study that I also included in the book, which showed that Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns would have earned a thousand times more in their lives if they got a cut of ten percent from any resale. NFTs do that. And this also touches on the cultural shift that we are seeing there, that speculation suddenly is something that doesn’t exclude people having invested in the beginning, but helps grow what they created.

[SD] Right, and there are maybe two components that are worth teasing out. The fact that royalties go to the artists when NFTs are resold is a cultural decision, which has a cultural history with curator Seth Siegelaub and his “The Artist’s Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement” contract circulating among conceptual artists since the early 1970s, but it also has an architectural and infrastructural element to it, because with NFTs, rights are hardwired, hard-programmed into it. When a resale takes place, nobody has to settle that account. It just directly goes to the artist. The fact that it’s so easy, that you can’t really mess with that when you have the asset, makes it a lot more possible to do this artist resale royalty that has been demanded for so long. But in different jurisdictions they have different laws, and within those jurisdictions it’s not always enforceble. So, this new infrastructure says, it desn’t matter where you buy. The minute that the transaction takes place, the royalty goes to the artist. It’s not a social game, it’s an infrastructure game.

This text was also published in Lerchenfeld No. 61.

This public conversation was conducted by Kolja Reichert and Simon Denny on 28 February 2022 at Villa Grisebach in Berlin on the occasion of the publication of Krypto-Kunst in Wagenbach Verlag’s series Digitale Bildkulturen. The passages printed here are taken from a live recording that can be watched on the YouTube channel of Digitale Bildkulturen.

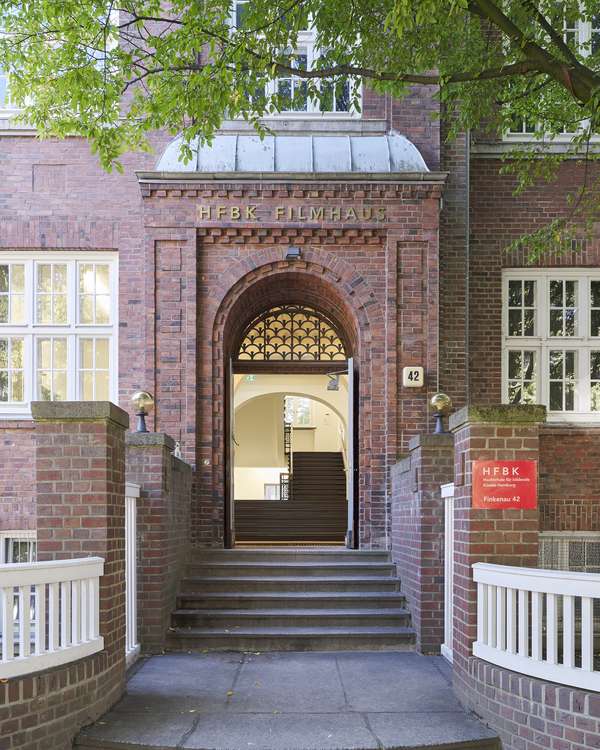

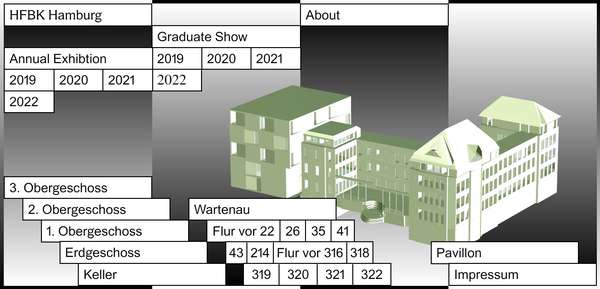

Simon Denny has been Professor of Time-based Media at the HFBK Hamburg since 2018. In his internationally shown exhibitions, he artistically explores the social and political impact of the tech industry and the rise of social media, startup culture, blockchain, and cryptocurrencies.

Kolja Reichert is an art critic and has worked as an editor for Spike Art Quarterly, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, and the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung. Since June 2021, he has been curator for discourse at the Bundeskunsthalle in Bonn.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Long days, lots to do

Long days, lots to do

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

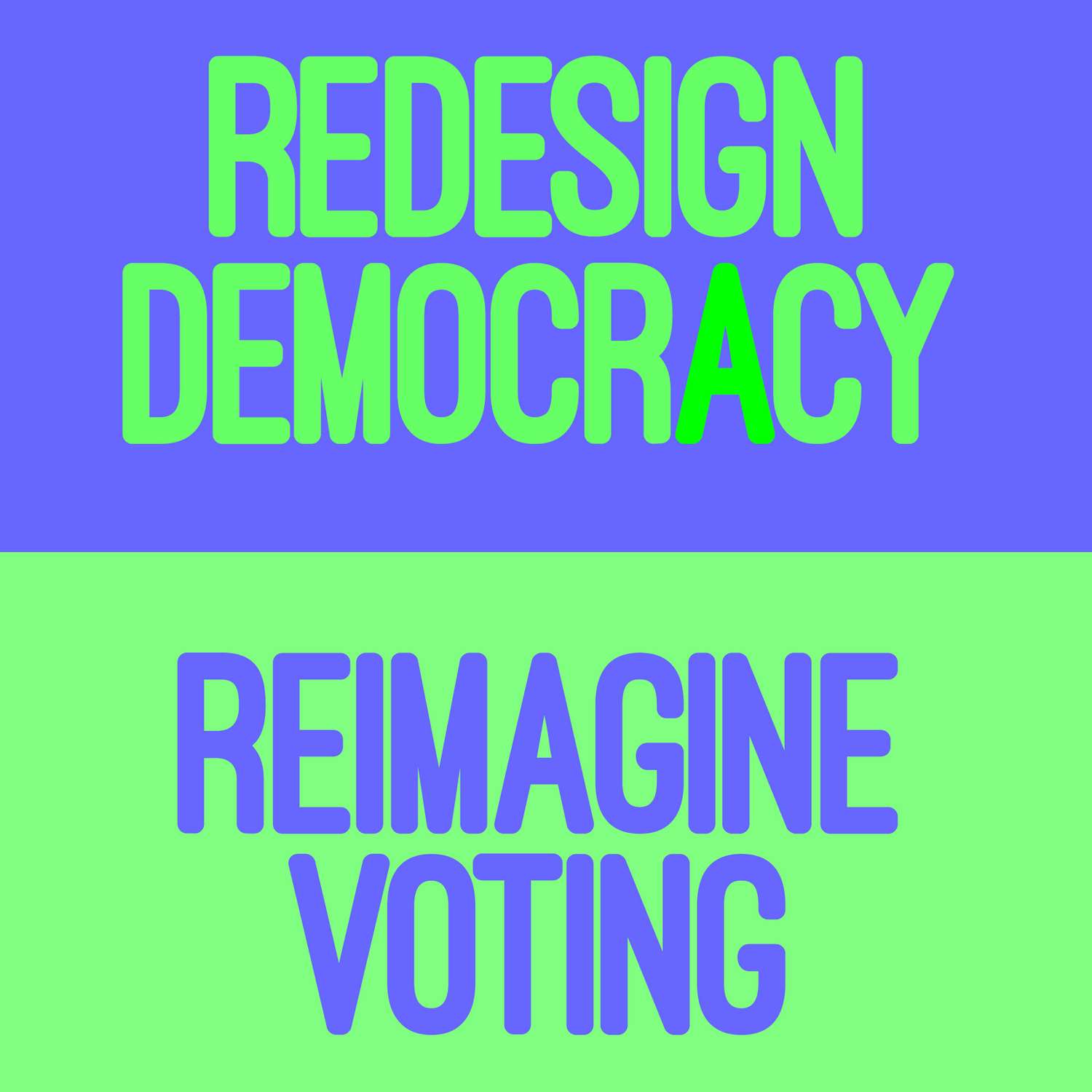

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Redesign Democracy – competition for the ballot box of the democratic future

Art in public space

Art in public space

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: study at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2025 at the HFBK Hamburg

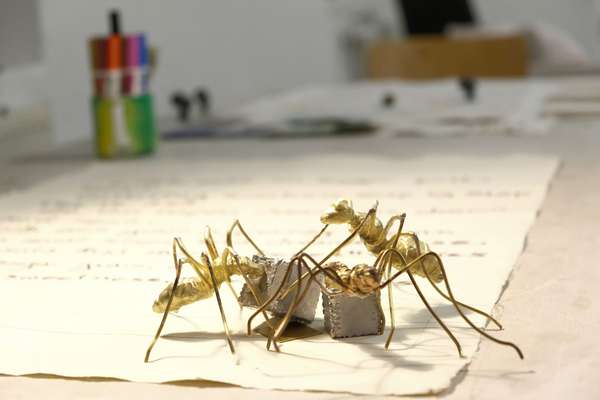

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

The Elephant in The Room – Sculpture today

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

Hiscox Art Prize 2024

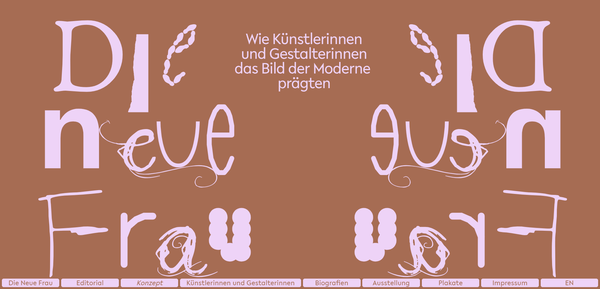

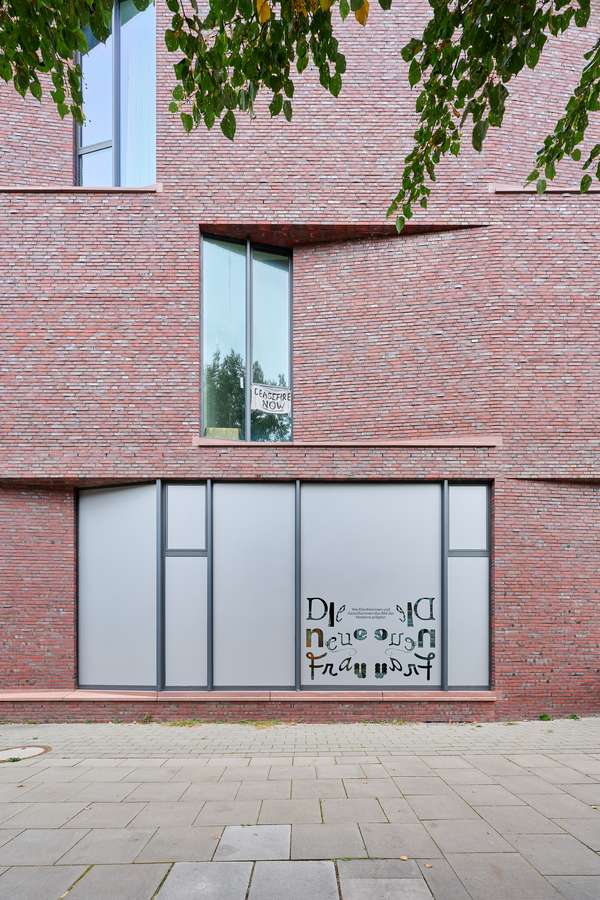

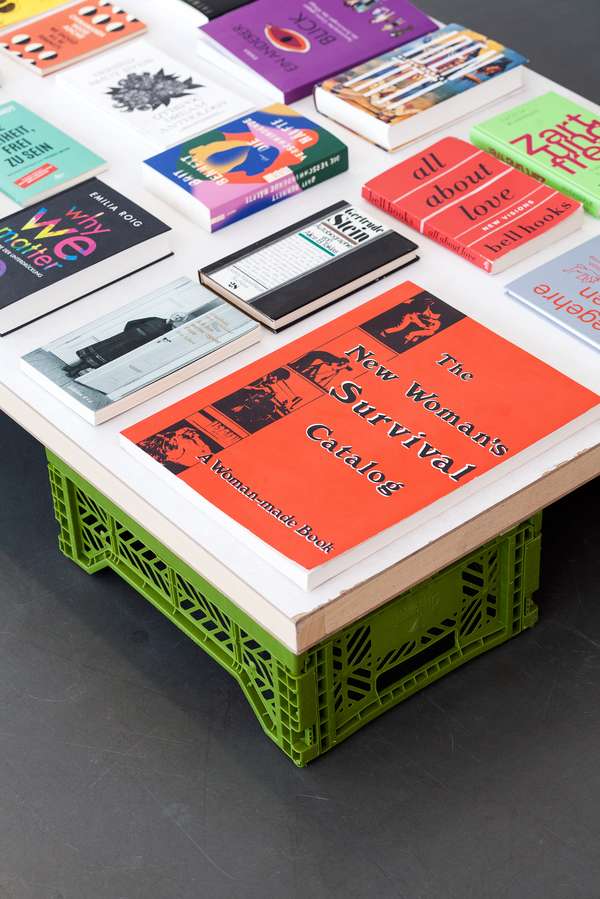

The New Woman

The New Woman

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Doing a PhD at the HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2024

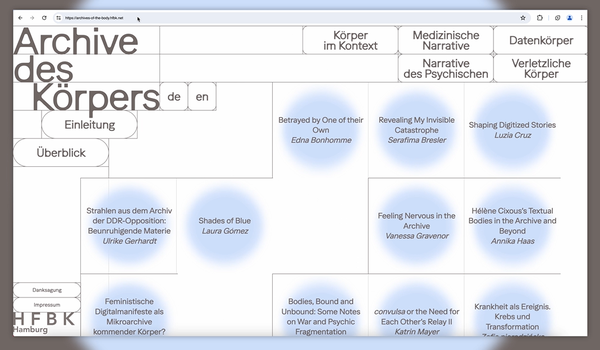

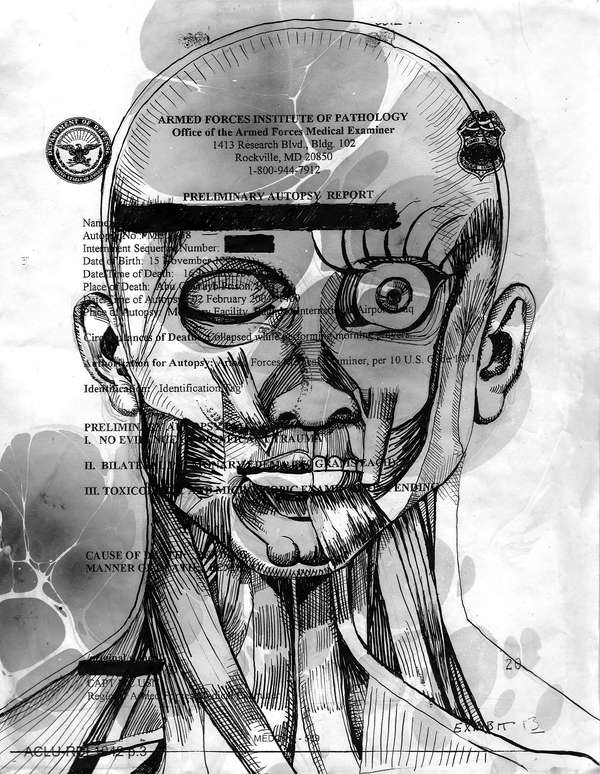

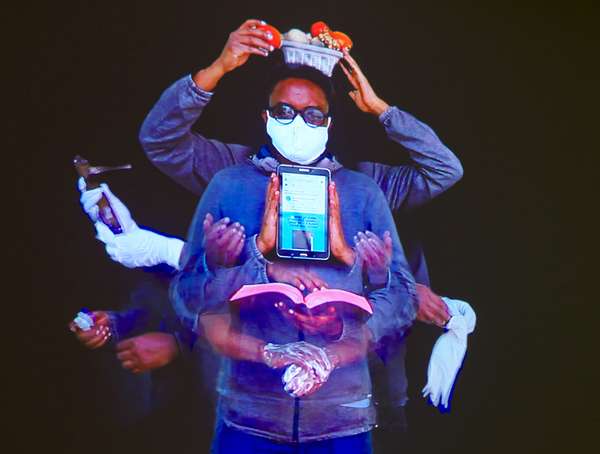

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

New partnership with the School of Arts at the University of Haifa

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2024 at the HFBK Hamburg

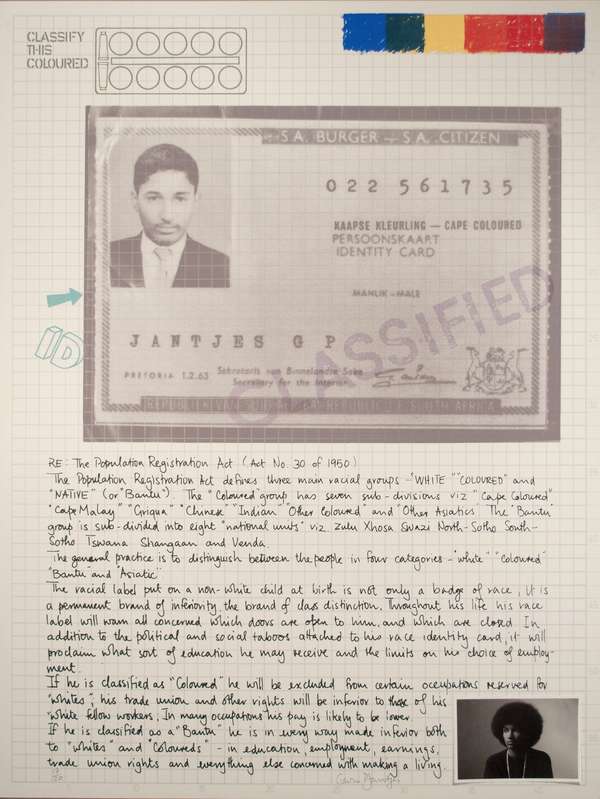

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

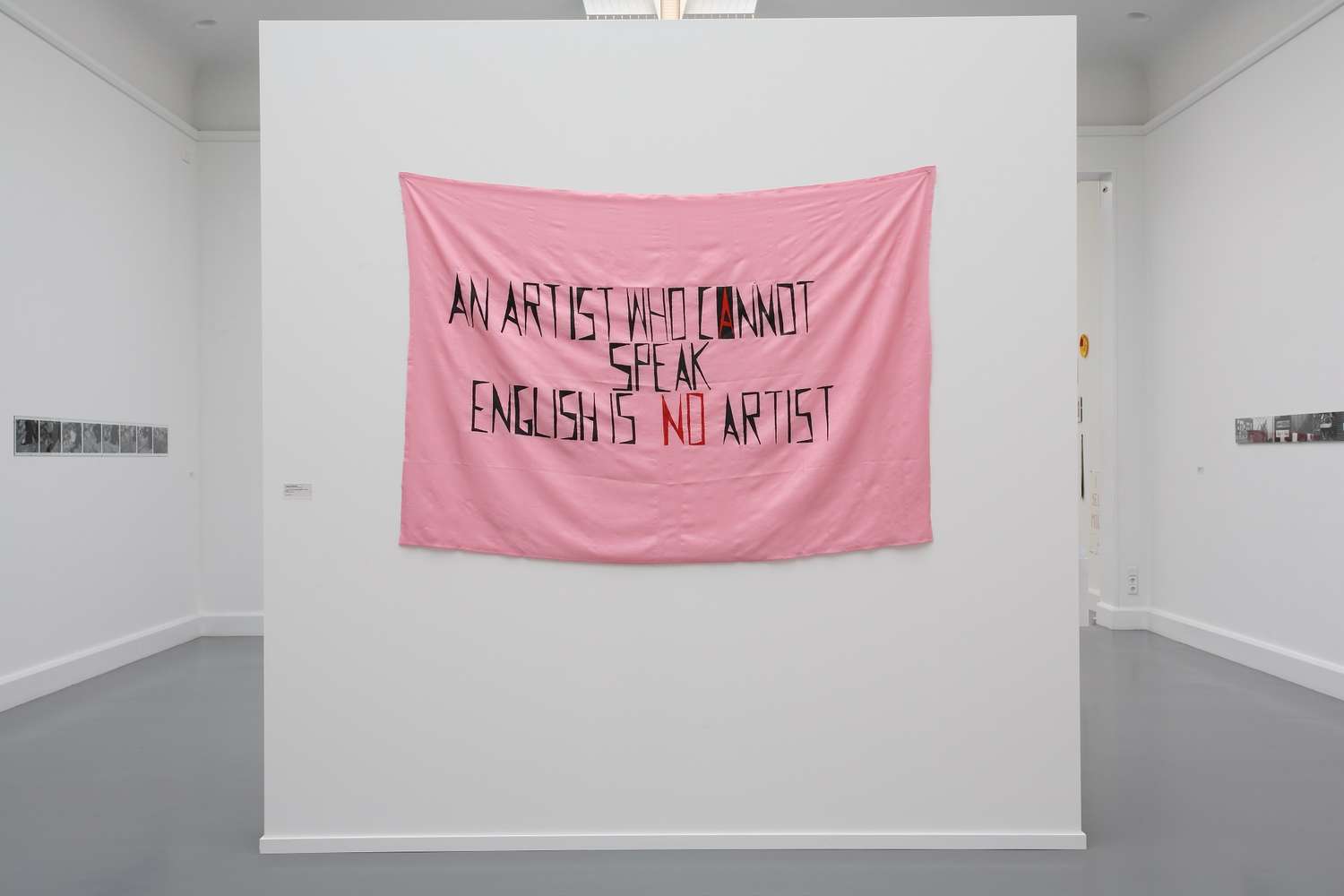

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

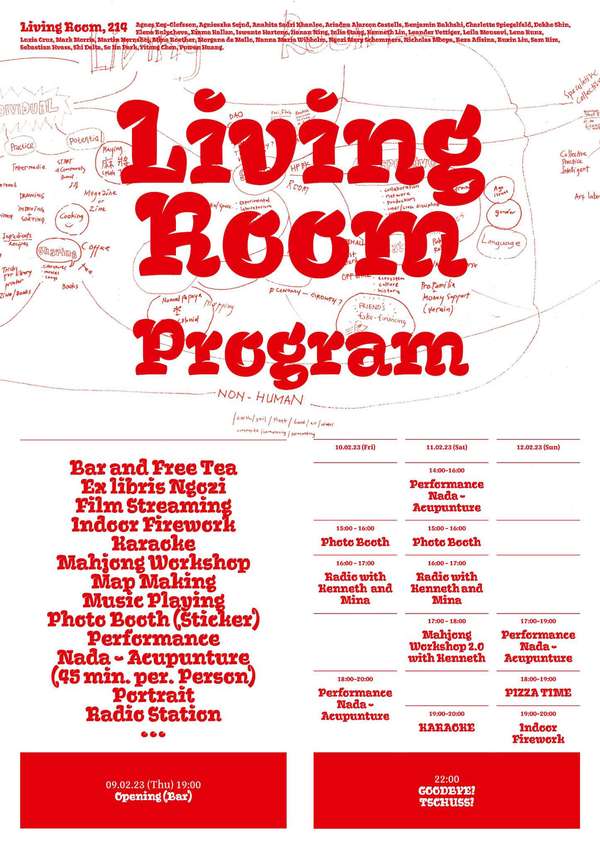

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

Annual Exhibition 2023 at HFBK Hamburg

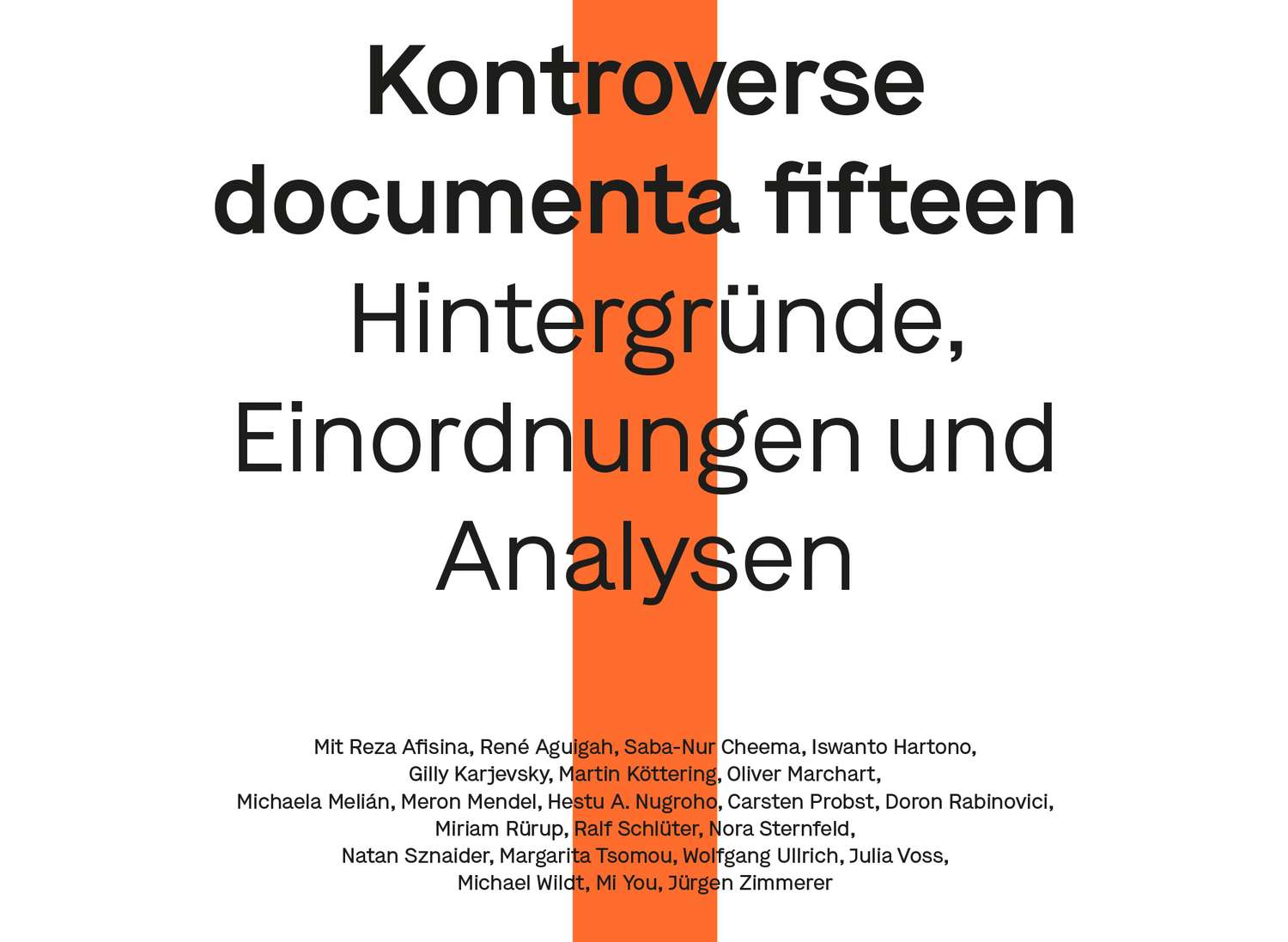

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Symposium: Controversy over documenta fifteen

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival and Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

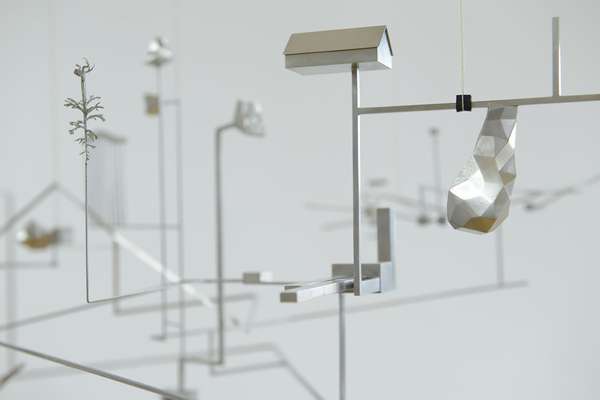

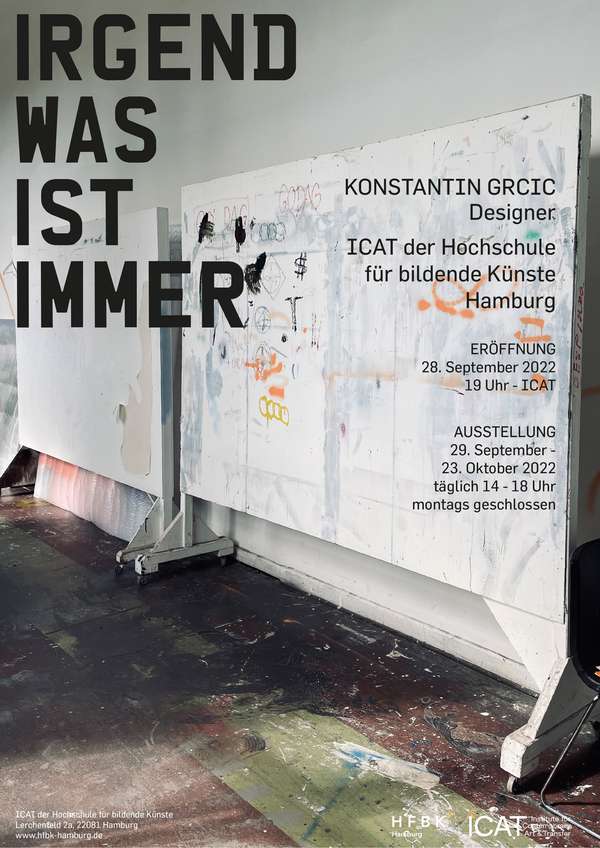

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Solo exhibition by Konstantin Grcic

Art and war

Art and war

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

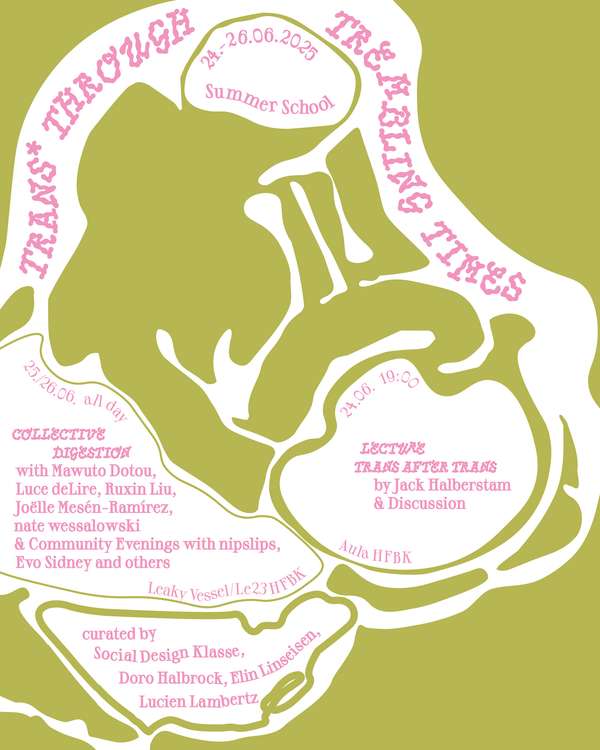

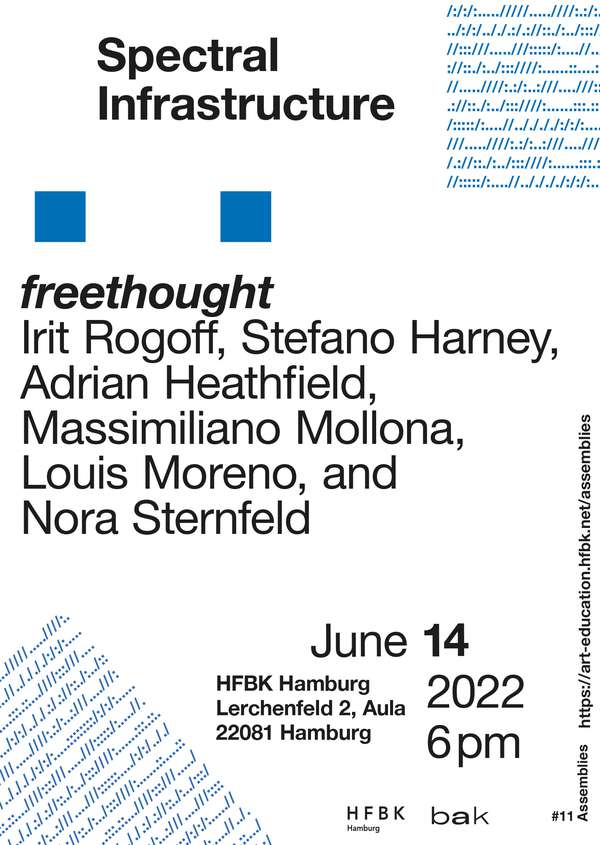

June is full of art and theory

June is full of art and theory

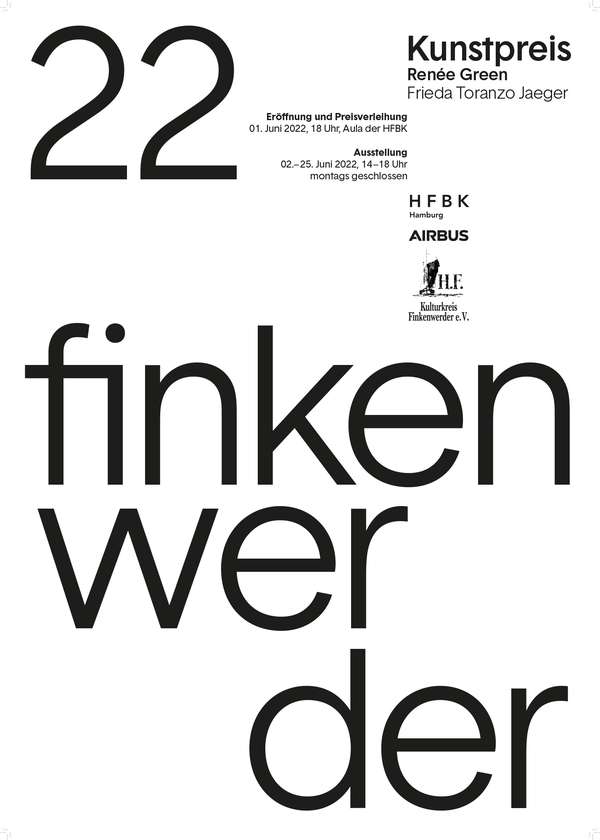

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

Finkenwerder Art Prize 2022

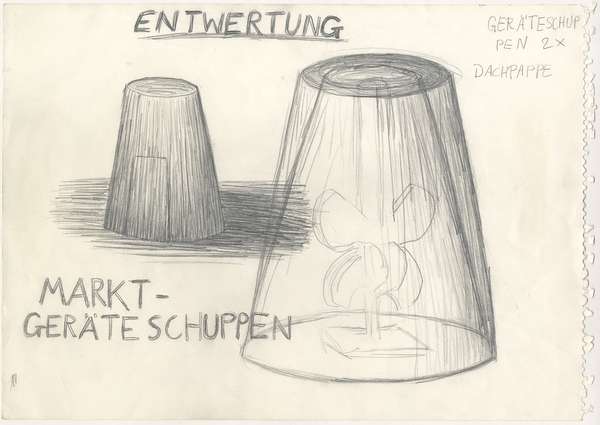

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2022 at the HFBK

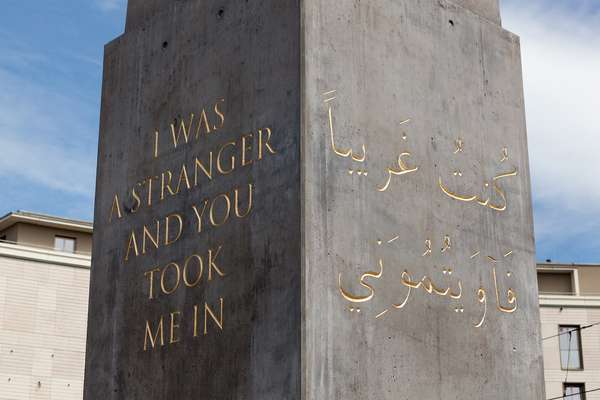

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments.

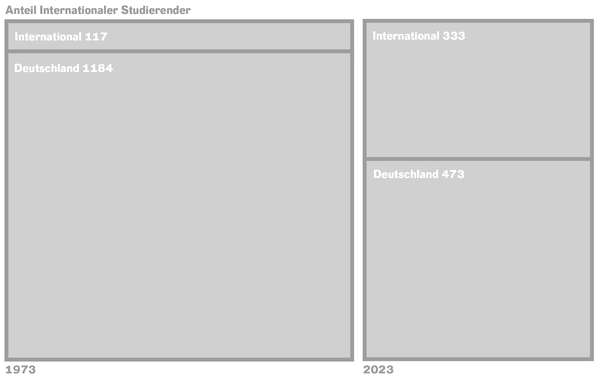

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

Unlearning: Wartenau Assemblies

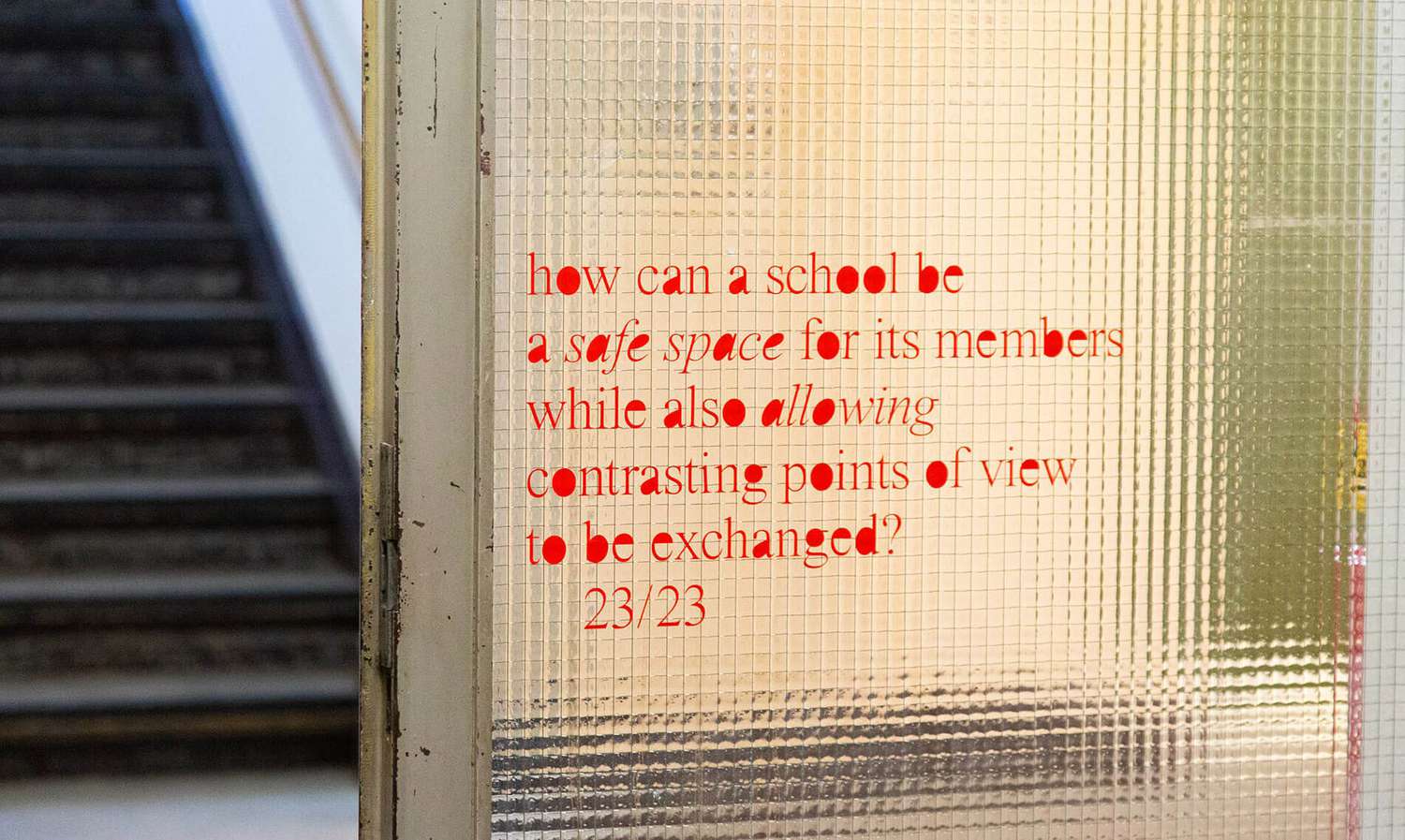

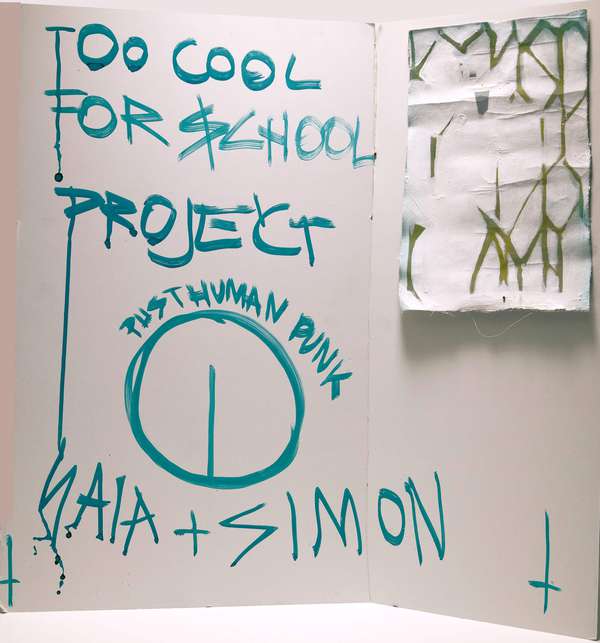

School of No Consequences

School of No Consequences

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Annual Exhibition 2021 at the HFBK

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

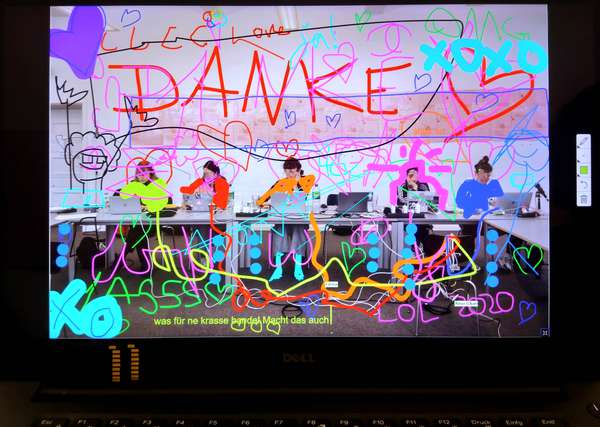

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

Teaching Art Online at the HFBK

HFBK Graduate Survey

HFBK Graduate Survey

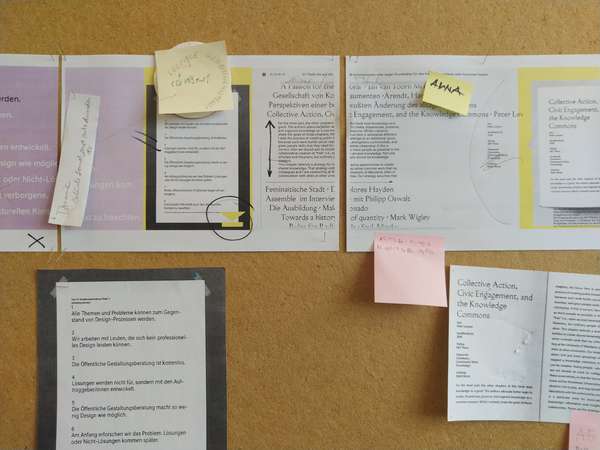

How political is Social Design?

How political is Social Design?