Notions of Non-Property

In her artistic works, Marwa Arsanios deals with the question of ownership and commons. Together with the writer and curator Lama El Khatib, she will develop a program of various events on the topic at the extended library at HFBK Hamburg during her fellowship at the Hamburg Institute for Advanced Studies (HIAS) in the upcoming semester

Marwa Arsanios and Lama El Khatib

Lama El Khatib: Together we are trying to put forth a notion of “non-property” as a theoretical and practical tool that can rub against (rather than negate) and undo (rather than conceal) the category of property; understood here in its historic, economic, political, social, and intellectual dimensions. In the following conversation, we want to elaborate on the ways in which we arrived at “non-property” and how we are shaping and reshaping the term’s forms, meanings, and scope in collaboration with others and through various approaches and formats.

Marwa Arsanios: I've been in close conversation with various communities that are trying to establish a different relationship to property through their praxis and lives[1]. After many years of working alongside and in dialogue with these practitioners, thinkers, and activists I am continuously returning to the question: How can the lessons I’ve learned from their territories and struggles travel, get translated and adapted to different territories, contexts and fields including art? How do we disseminate these relationships of “non-property” and allow them to enter different realms and corners?

Lama El Khatib: In these contexts that you have engaged in, various forms of property relations are challenged or taken up as sites of struggle - yet, land always appears as a central stake; in other words, a move towards non-property always sits in close proximity to the histories and continued legacies of land struggles.

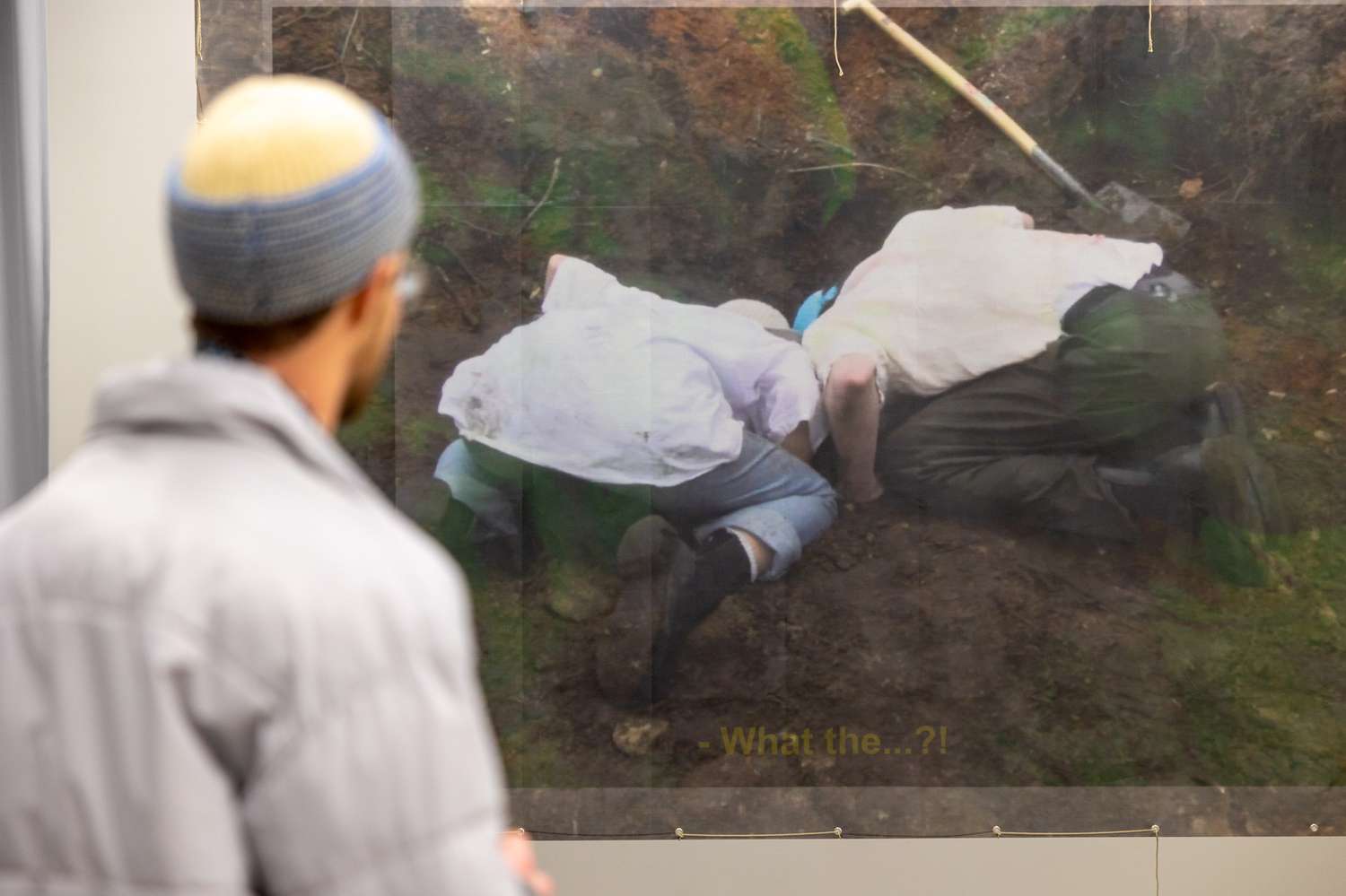

Marwa Arsanios: The land question comes in as a starting point for thinking about the category of property but also as the site in which it can be directly challenged. This is because the land (in its various constituents) opens up to other relations and questions through for example practices of agriculture and farming, but also histories of extraction and value creation, of financialization and commodification. One cannot think about the question of property without addressing notions of worth, of value, etc. Also, can we really think of the question of property without thinking of the question of production? Such as agricultural production. We come to understand that they are inherently connected and that Land makes explicit that the consequence of challenging property is also challenging a mode of production and value-making processes.

Lama El Khatib: Property in this sense is understood as a relation that persists on multiple fronts. In that line, non-property proposes an alternative relation or rather an alternative form of relation.

Marwa Arsanios: What form does this relation to the land take? Is it one of ownership? Or usership? Of custodians? Or collective maintenance? What form could potentially lead to a non-possessive relation? To a form of non-property? All these formal questions can unfold into strategies.

Lama El Khatib: I want to return to this image of contamination that you mentioned earlier because it prompts or references a very specific form of learning that is more akin to a kind of study in which practices spill over rather than get applied and reapplied.

Marwa Arsanios: It is important to think about how ideas and ideologies travel. It's not the model of the modernist universal housing unit that is sent to be reproduced in different contexts around the world. It's rather the very relation that is traveling, a relation that counters the capitalist abstraction of possession and extraction. This is maybe what is interesting about this question of contamination here. How abstractions or a relation travel and boomerang back. We end up producing different micro economies of non-property relations that keep on contaminating each other and can slowly form a kind of an infrastructure. sense, there is also political internationalism that is formed.

Lama El Khatib: For me, what was really interesting from the very start was to think about why property seemed like such a place to intervene in. And that is because of the kind of stability that term appears to have both historically and at this moment. As a spatial or geographical concept, it feels unshakable. The historic development of that term is just erased and one cannot process it as something that has been historically instantiated and manufactured intellectually, economically or socially. And I think these practices that propose and live out alternatives point to the fragility of these kinds of categories. There is an inherent instability to the term. It is an intellectually, politically, economically formed category. And we can reform it and un-form it, or completely get rid of it.

Marwa Arsanios: Yes. I think this is where contamination can play a role. Contamination as a strategy that would intervene geographically in specific territories but also in time and history. It is important to understand that these practices of non-property are sometimes precarious; they do not have a future in an institutional sense (state institutions) but they already intervene in the political imaginary the moment they are set as an experiment. It is important to aim for a different temporality for this non-property relation but at the same time be aware that the impossibility of institutionalizing it is an inherent part of the struggle. And what happens the moment this relation takes form in the world, is that it intervenes in our ability to perceive land for example. We already start seeing the instability of that system that you are in now.

Lama El Khatib: In this context, the definition of non-property takes its cue also from the ways in which abolition[2] has come to be defined. Non-property is a proposition for a future or a horizon in which property is not a stable category that governs our legal, social, political lives. But at the same time, it is the set of practices and the forms of organizing here and now. And not individual practices developed in isolation but ones that are spilling over or contaminating practices that have existed historically and continue to exist.

Marwa Arsanios: Yes, we might say that it is a calling from a past towards a future proposition where a history of commoning has not been crashed.

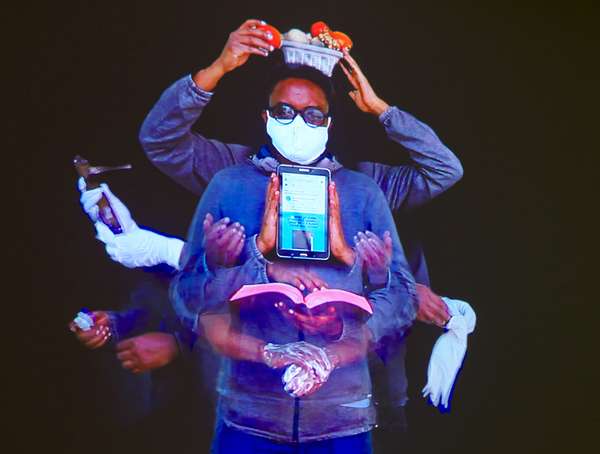

Marwa Arsanios’ practice tackles structural and infrastructural questions using different devices, forms and strategies. From architectural spaces, their transformation and adaptability throughout conflict, to artist-run spaces and temporary conventions between feminist communes and cooperatives, the practice tends to make space within and parallel to existing art structures allowing experimentation with different kinds of politics. Film becomes another form and a space for connecting struggles in the way images refer to each other. In the past four years Arsanios has been attempting to think about these questions from a new materialist and a historical materialist perspective with different feminist movements that are struggling for their land. She tries to look at questions of property, law, economy and ecology from specific plots of land. The main protagonists become these lands and the people who work them. Her research includes many disciplines and is deployed in numerous collective methodologies and collaborative projects.

Lama El Khatib is a writer and cultural worker based in Berlin. Since 2018 she has worked at Haus der Kulturen der Welt as a curatorial coordinator, researcher, and producer. Her work draws on abolitionist traditions and is invested in a poetics of “the labor of the dead”.

[1] Amongst those communities are the Kurdish autonomous women’s movement and specifically Jinwar and Grupo Semillas (Colombia)

[2] Abolition is understood here as the body of thought and forms of organizing that take the prison-industrial complex as the site of study and its abolition as horizon and practice.

This interview was first published in the magazine "Lerchenfeld" No. 68.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

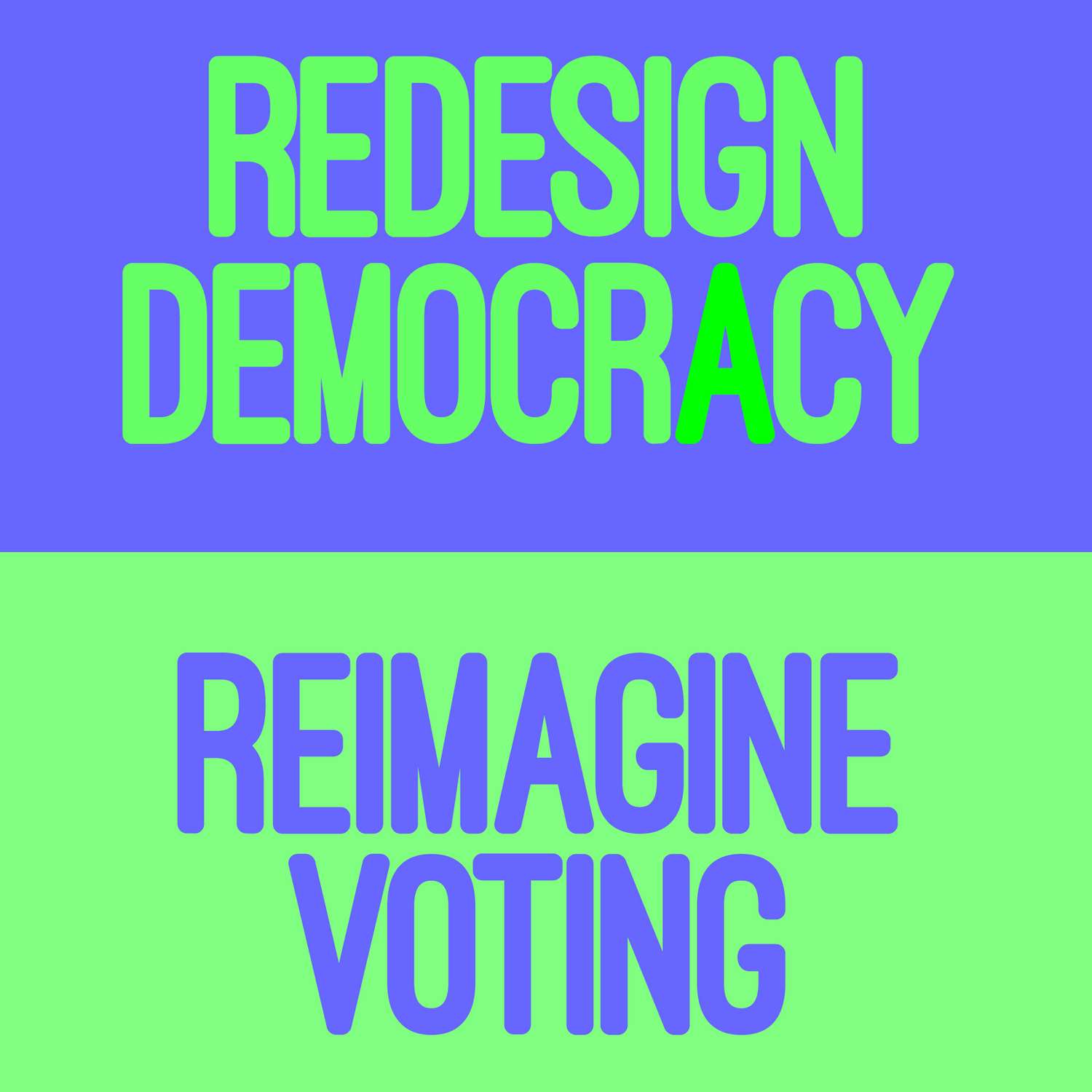

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Die Neue Frau

Die Neue Frau

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

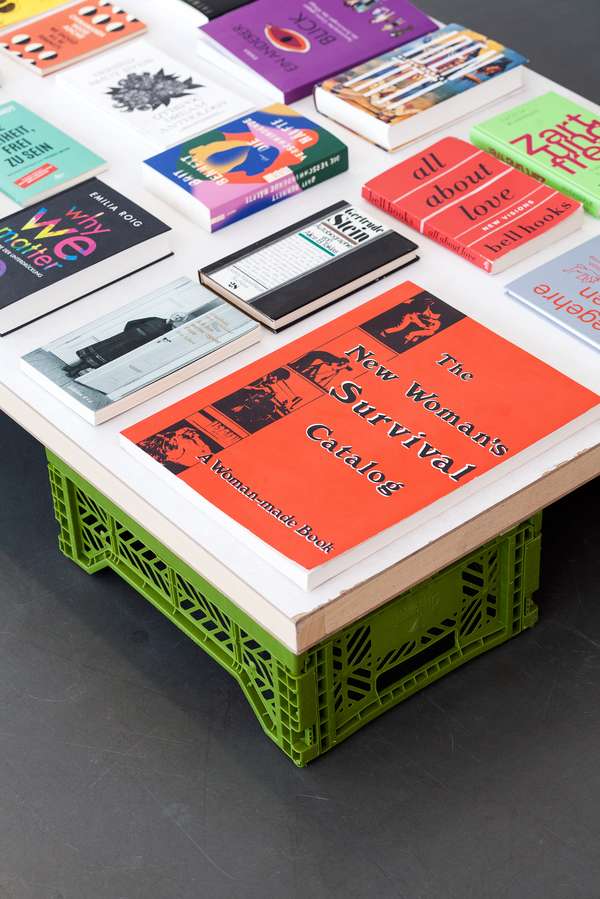

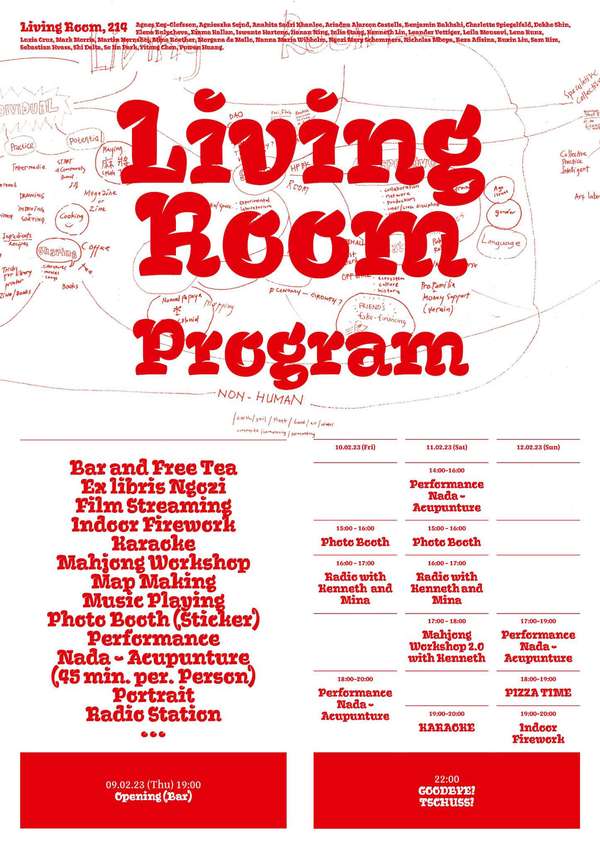

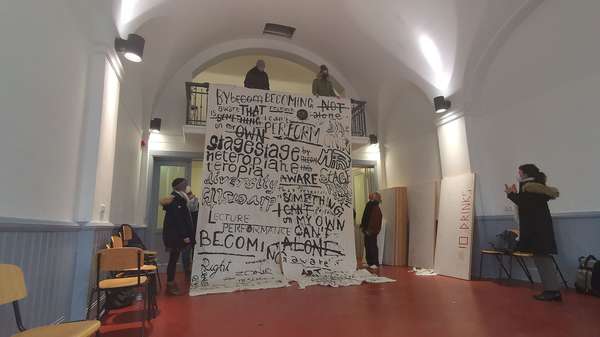

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

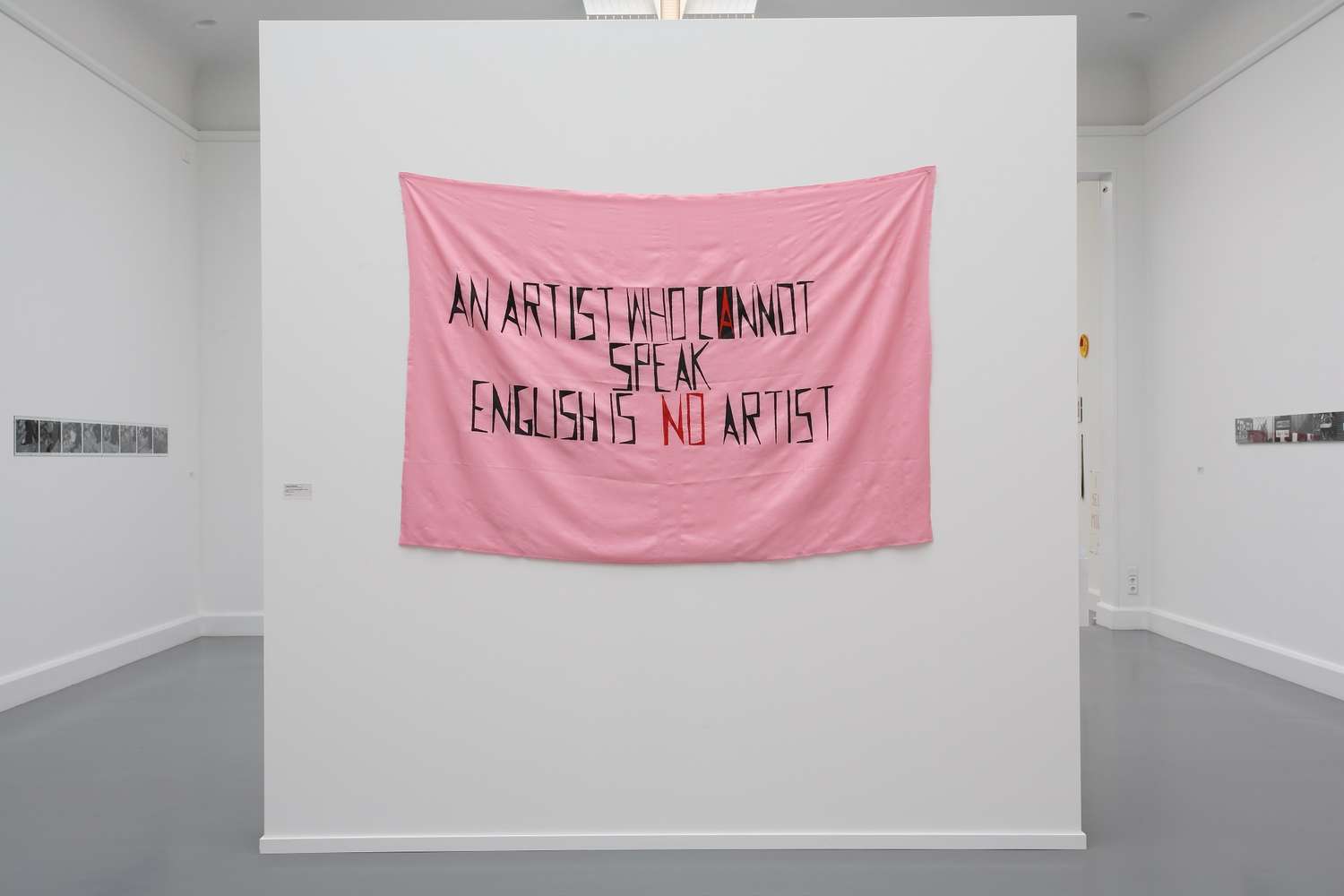

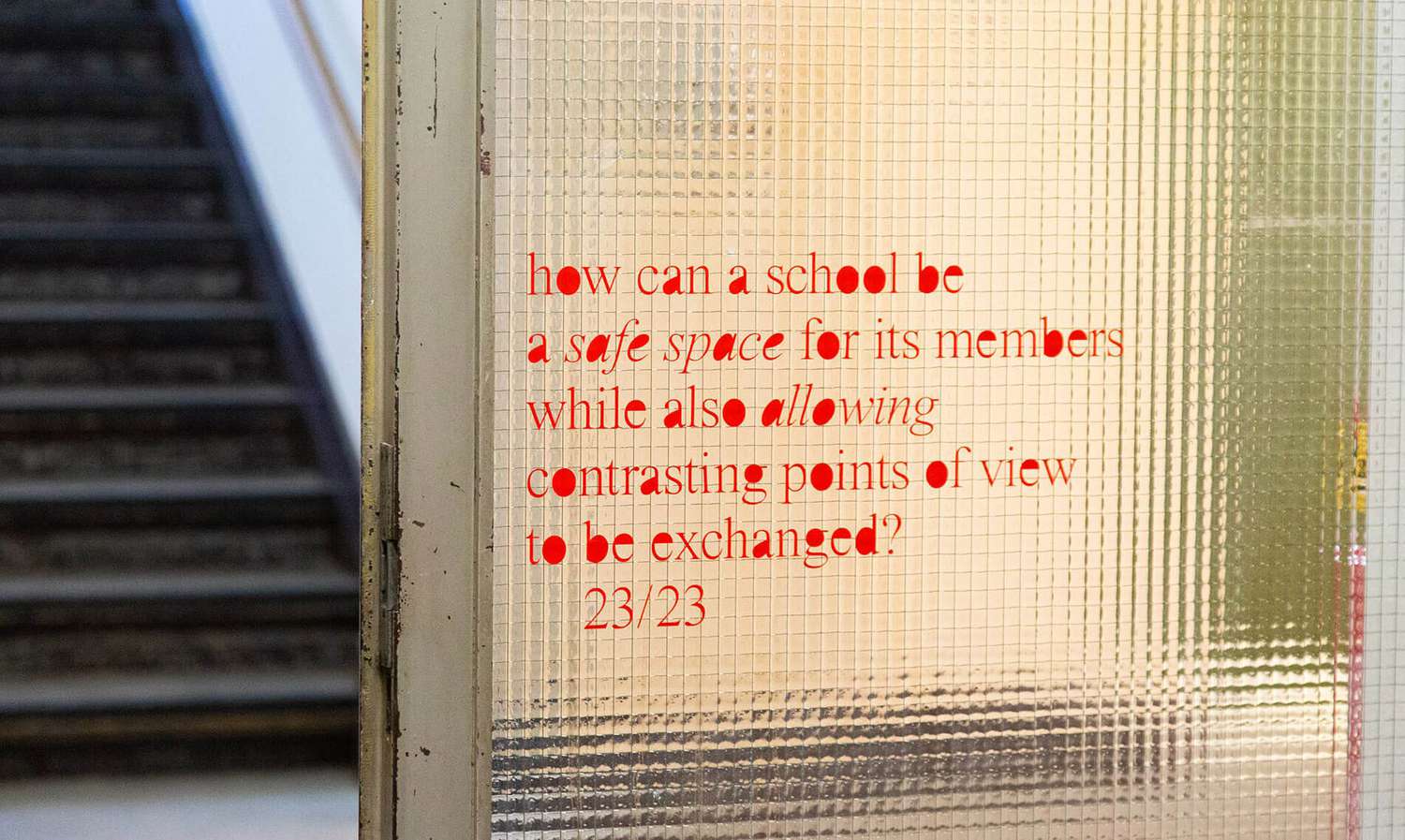

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

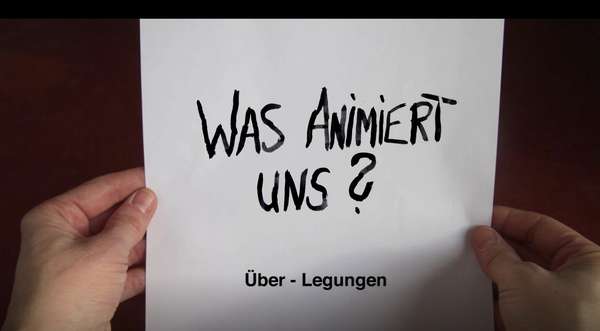

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

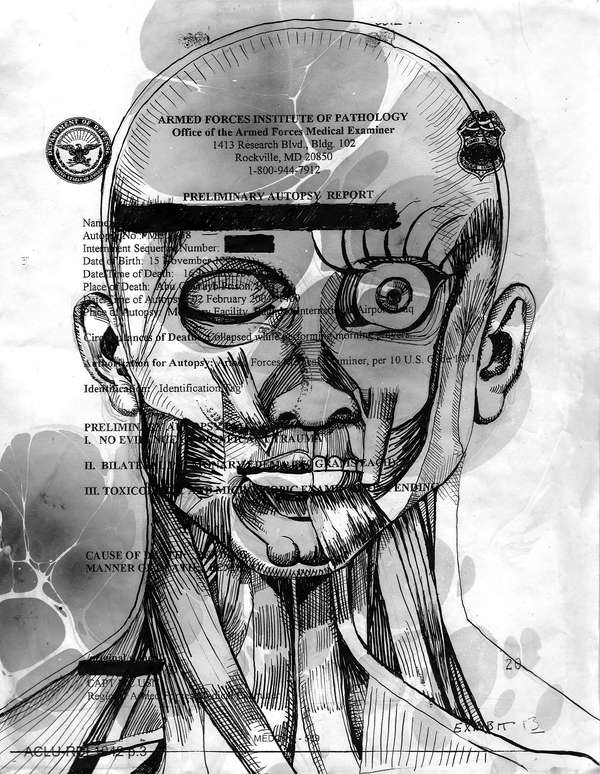

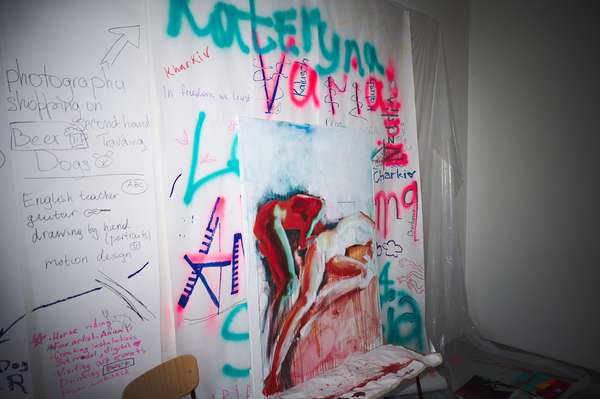

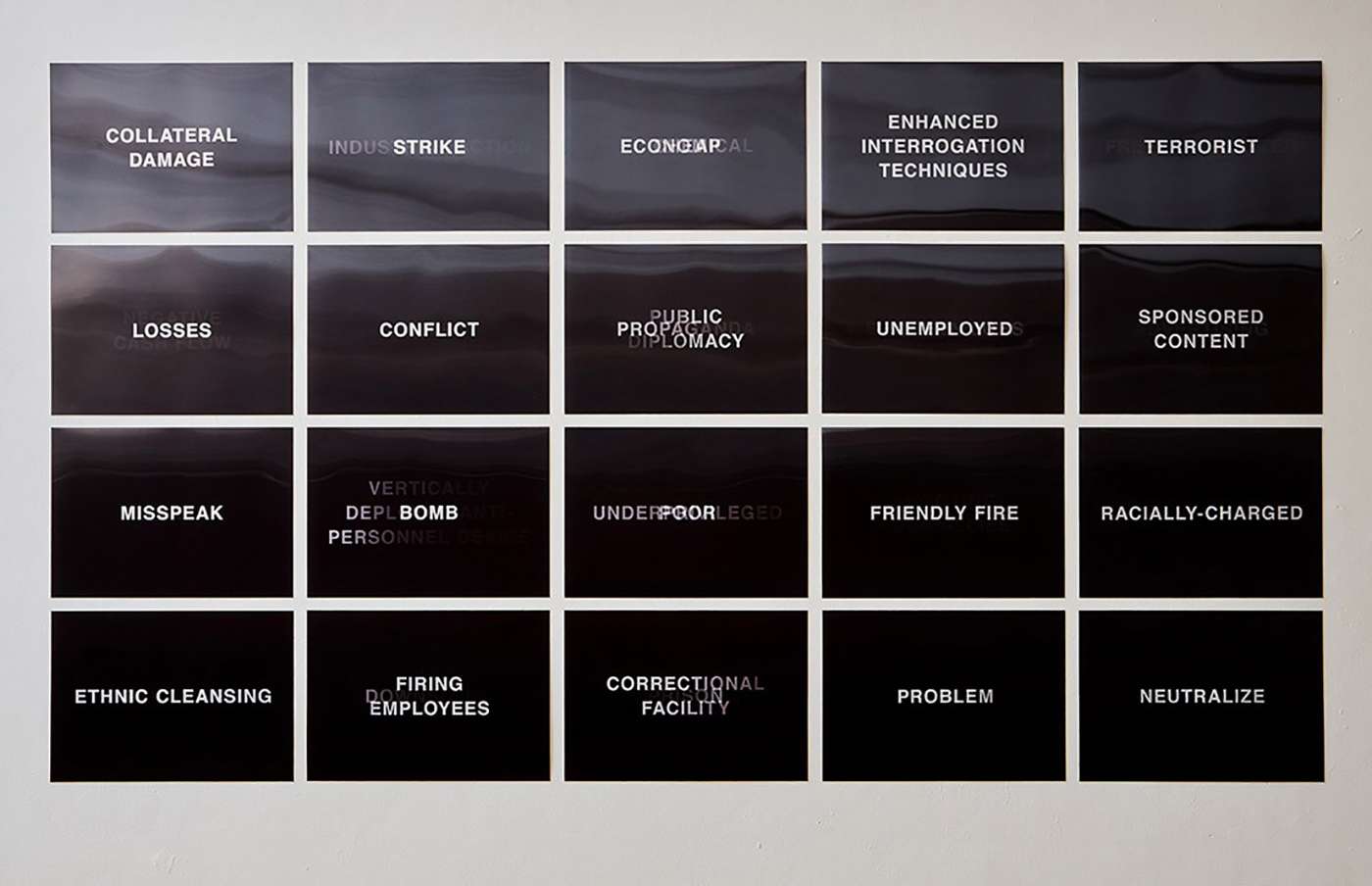

Kunst und Krieg

Kunst und Krieg

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

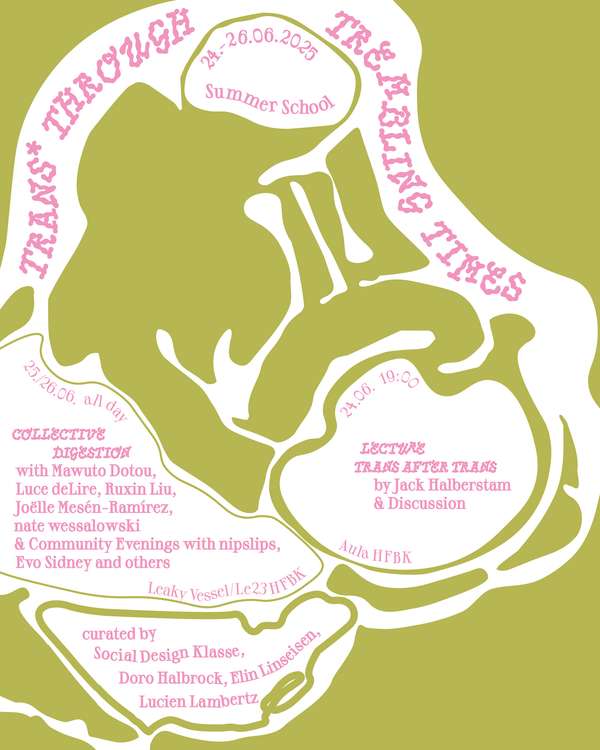

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

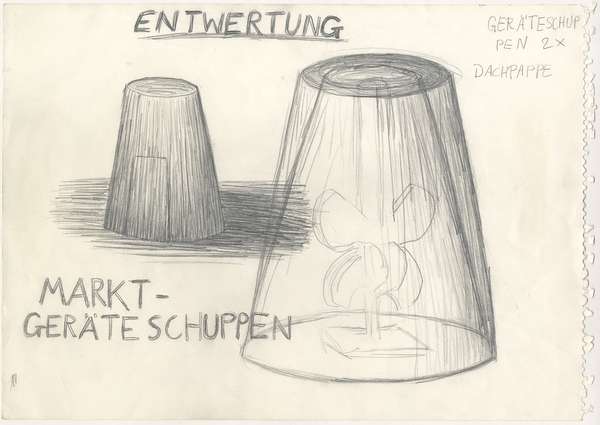

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

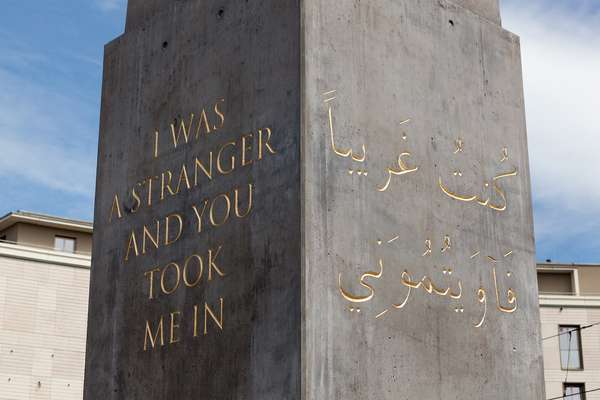

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

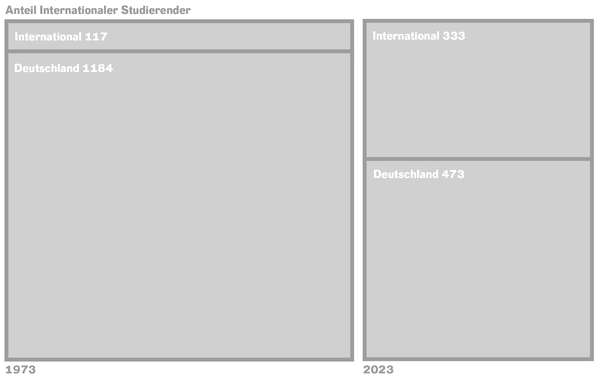

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

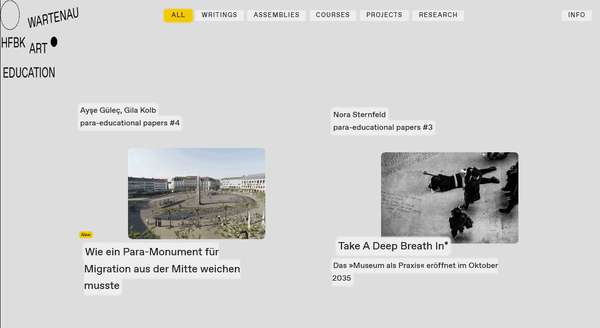

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

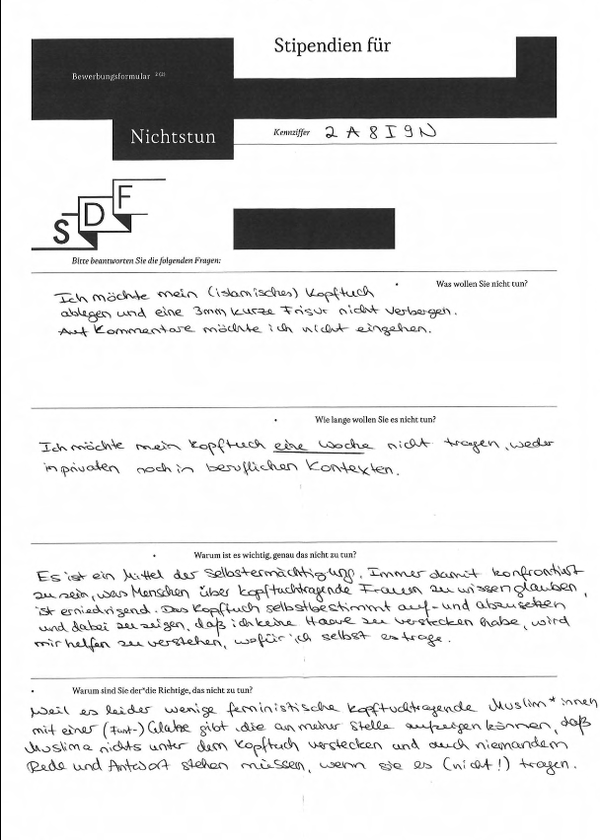

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

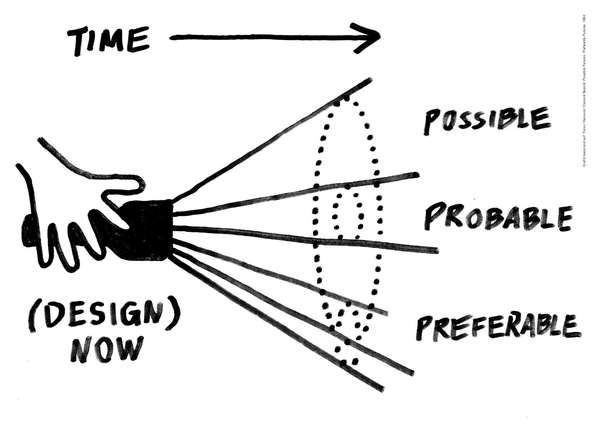

Wie politisch ist Social Design?

Wie politisch ist Social Design?