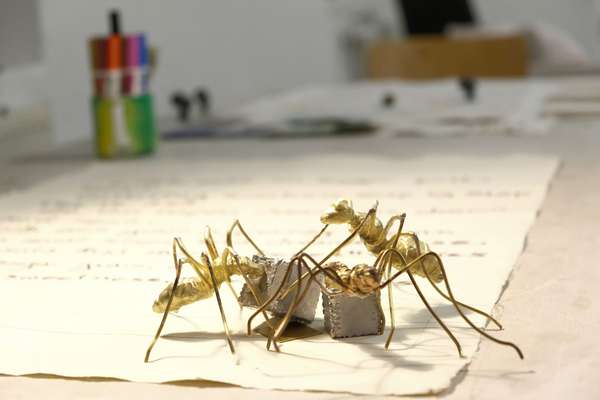

What do you actually do? – Sung Tieu

“The whole of Berlin used to be like this,” murmurs Sung Tieu as she peers into an abandoned building covered with graffiti and dust. We’re in West Berlin to climb Teufelsberg, a man-made hill that offers a grand 360-degree view of the city, and we’ve stopped to see the remains of the former American listening station positioned partway along the trail. Famous for its golf ball–like radomes, the station was used to intercept, listen to, and disrupt radio signals from the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War. Nearby, another visitor is playing with a drone and I’m reminded of how much warfare has changed in the intervening years. I ask Tieu—whose research-based work often explores instances of conflict in expansive installations comprising sculpture, text, and sound—if she’s ever made work about unmanned aerial vehicles. “No,” she replies firmly. “I’m not so much interested in the weapons themselves—it’s their psychological effects that concern me.”

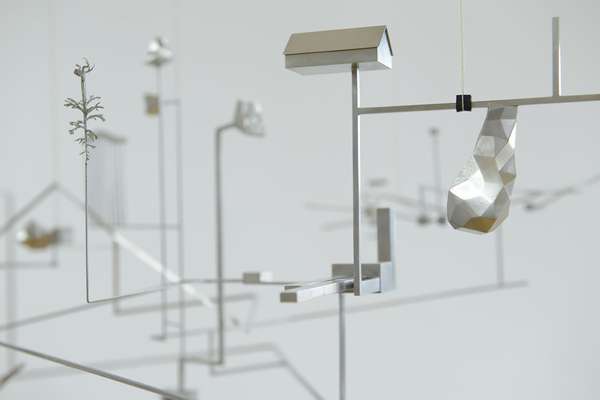

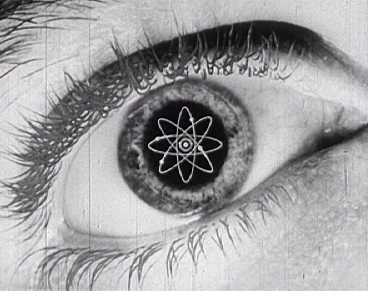

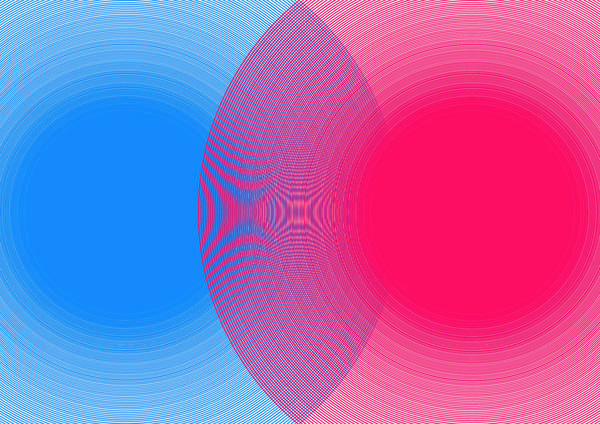

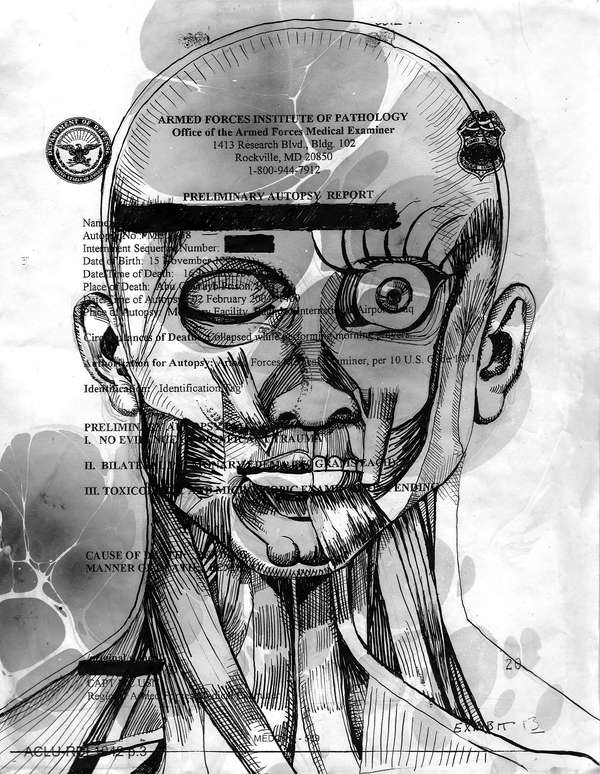

It’s true that there are no visible signs of weaponry in the German-Vietnamese artist’s visual output, but the threat of violence is everywhere. Her recent exhibition at Nottingham Contemporary looks specifically at sonic warfare through the lens of the so-called Havana Syndrome, the name given to a series of symptoms that were apparently experienced by the staff of the U.S. and Canadian embassies in Cuba after being subjected to aural assaults. First reported in 2016, the Trump administration considers the series of acoustic attacks to have been politically motivated and carried out by the Cuban government. Tieu was initially interested in this phenomenon, she tells me, because unlike other sonic weapons, which are mostly created by turning the volume up, the sound that ‘caused’ the Havana Syndrome was, in many cases, indistinguishable from other background noises. Is the weapon real? Tieu’s not so sure. Yet she was curious enough to expose herself to a reconstruction of the sonic attack, the results of which are displayed in a series of brain scans at the entrance of the exhibition.

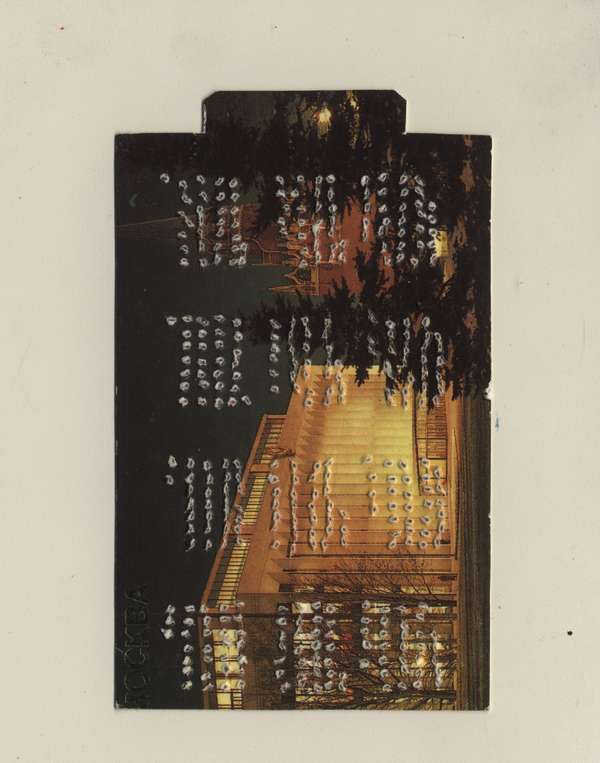

Tieu’s interest in the psychological effects of sonic warfare can be traced back to a visit she took to the Hien-Luong Bridge in central Vietnam in 2016. It’s there that Tieu first heard the story of Ghost Tape No. 10, an audio recording made by the U.S. Army that featured a Vietnamese man purportedly killed on the battlefield. Played by a Vietnamese voice actor, the ghostly figure implored his fellow comrades to flee or risk being killed in action. Similar tactics were used in World War II, when the Allies played audio recordings of tanks in an attempt to trick German soldiers into thinking they were outnumbered. But what made this technique novel during the war in Vietnam is that the recording capitalized on the commonly held Vietnamese spiritual belief that without proper burial rites the souls of the dead are trapped in an eternal hell and will never rest. Tieu has a begrudging respect for the diabolical cleverness of this operation: “Tapping into this well-known belief was so effective that people in Vietnam are still looking for the bones of their relatives today,” she says, sadly. “It’s a big business.’”

The irony that the U.S. has accused another nation of something they themselves have admitted to doing is not lost on Tieu. In Nottingham, she bridges these two stories together through four fabricated newspaper articles—part of the artist’s series Newspaper 1969 – ongoing—contained in vertical TV screens spread throughout the space. By positioning an article on PSYOPS, the style of operations that led to Ghost Tape 10, alongside a report detailing the political fallout of the alleged attack in Havana, Tieu shows the various ways in which U.S. diplomatic relations are still tied to Cold War ideologies. “The whole relationship between America and Cuba is still based on the ideological threat communism supposedly poses to the American way of life,” she says.

By participating in an ever-growing number of unwinnable wars—against communism, terror, crime, drugs—governments can slowly chip away at their citizens’ rights while at the same time claiming to protect them. But in order for this to work, people need to be kept in a constant state of hyper vigilance against possible threats to their way of life. Cleaved in half by concrete pillars and fencing, this paranoia is reflected in Tieu’s oppressive exhibition design, as well as in a number of sculptures scattered throughout the space. Made up of military-style clothing, these sculptures and their dispersal reflects the post-9/11 fear of bombs being left in unattended luggage in public spaces—a threat that Tieu became aware of when she moved to London in 2015. When the artist first showed a similar work at her 2018 exhibition at The Royal Academy, each object was accompanied by a different field recording. “You might hear the sound of crickets,” Tieu explains, “then a helicopter comes in, mixed with the sounds of fireworks going off and you suddenly feel as if you are in a danger zone. For someone who might have experienced a trauma, even harmless noises can be associated with danger."

Since then sound has been a reoccurring element in Tieu’s multilayered installations. As viewers weave their way around her exhibition in Nottingham, they are accompanied by a multichannel sound work, made in collaboration with composer Ville Haimala and psychologist Christian Sumner, which is based on Tieu’s brain waves captured with an EEG scanner while subjecting herself to a recreation of the Havana Syndrome sonic attack. She might have come out of the experiments seemingly unscathed, but amongst the array of conflicting information and conspiracy theories, it’s impossible not to question her version of events. After spending time in Tieu’s orbit, threats loom all around: every unattended bag a bomb, every drone hobbyist a possible enemy combatant.

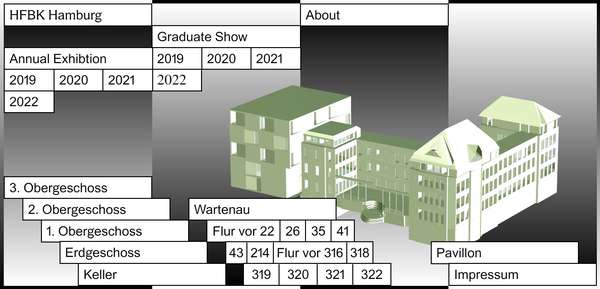

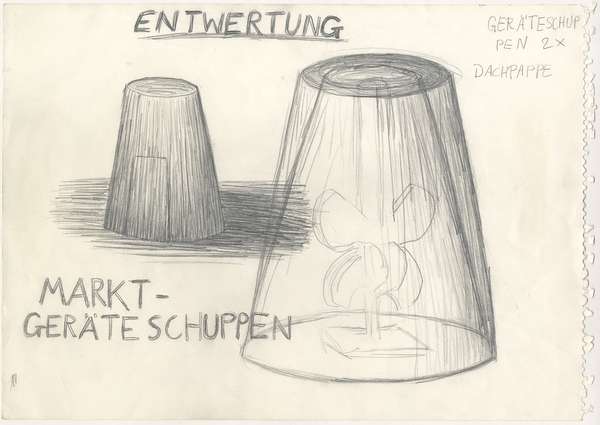

Sung Tieu is a German / Vietnamese-artist based in Berlin and London. She studied at the HFBK from 2009-2013 in the class of Andreas Slominski. Recent solo exhibitions include In Cold Print at Nottingham Contemporary, and Zugzwang at Haus der Kunst, Munich, both 2020.

HFBK graduate Chloe Stead, together with the photographer and also HFBK graduate Jens Franke, met former HFBK students to talk about work, life and art.

What do you actually do? – Mirjam Thomann

What do you actually do? – Mirjam Thomann

What do you actually do? – Niclas Riepshoff

What do you actually do? – Niclas Riepshoff

What do you actually do? – Astrid Kajsa Nylander

What do you actually do? – Astrid Kajsa Nylander

What do you actually do? - Hannah Rath

What do you actually do? - Hannah Rath

What do you actually do? – Roman Schramm

What do you actually do? – Roman Schramm

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

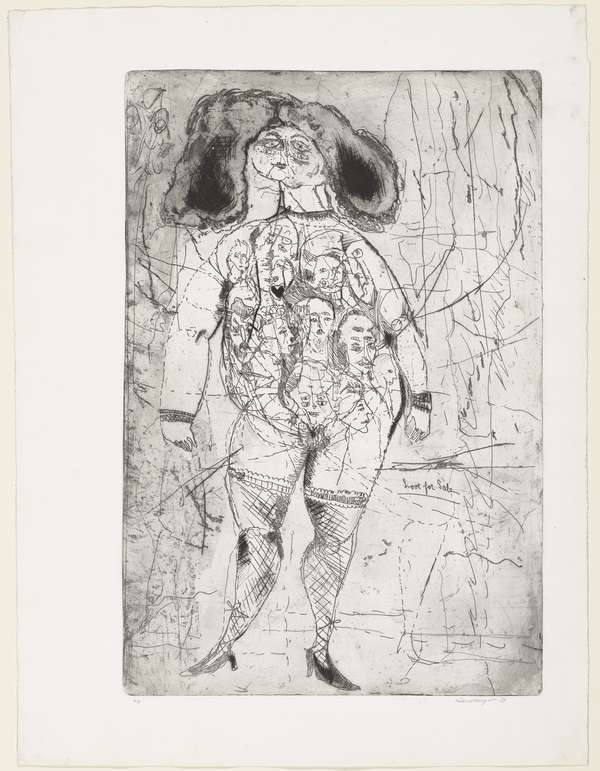

Die Neue Frau

Die Neue Frau

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

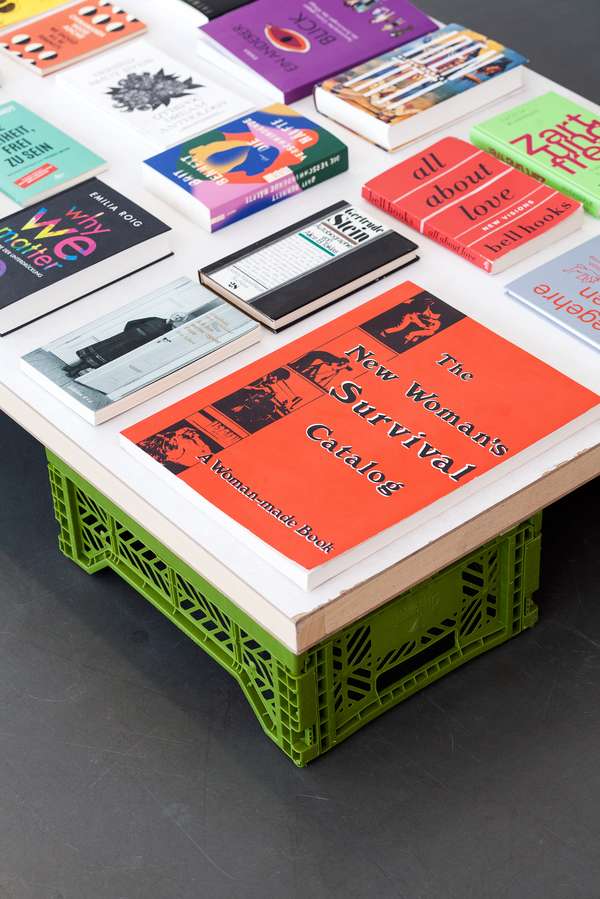

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

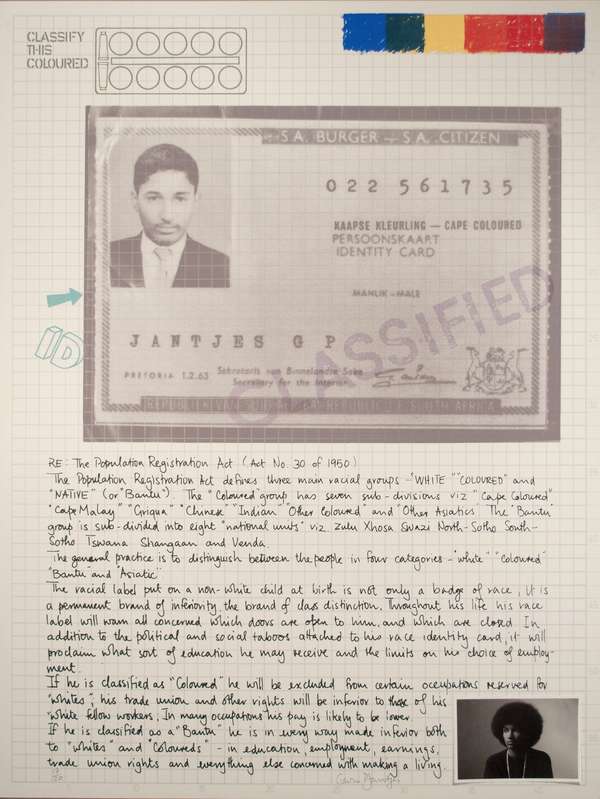

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

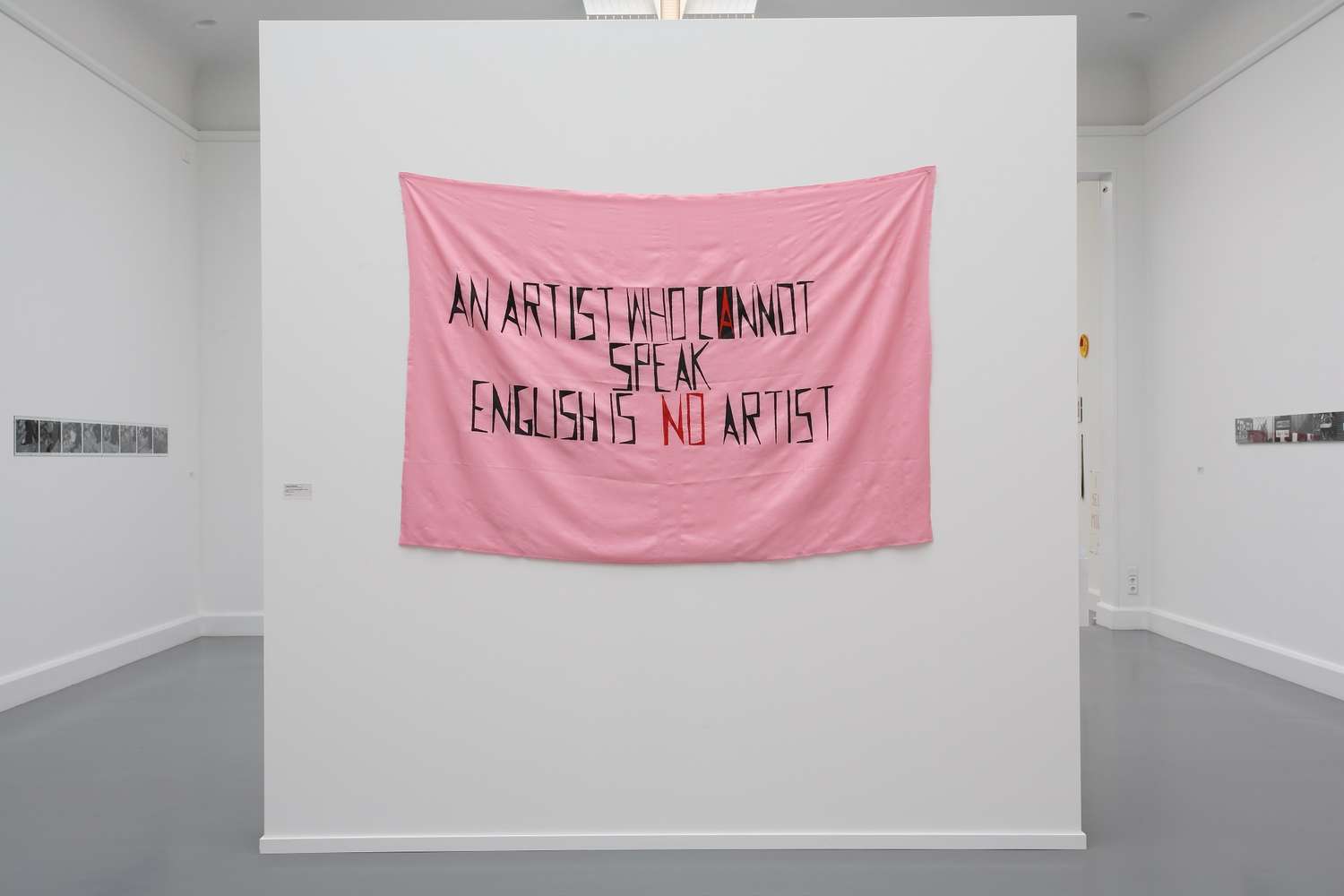

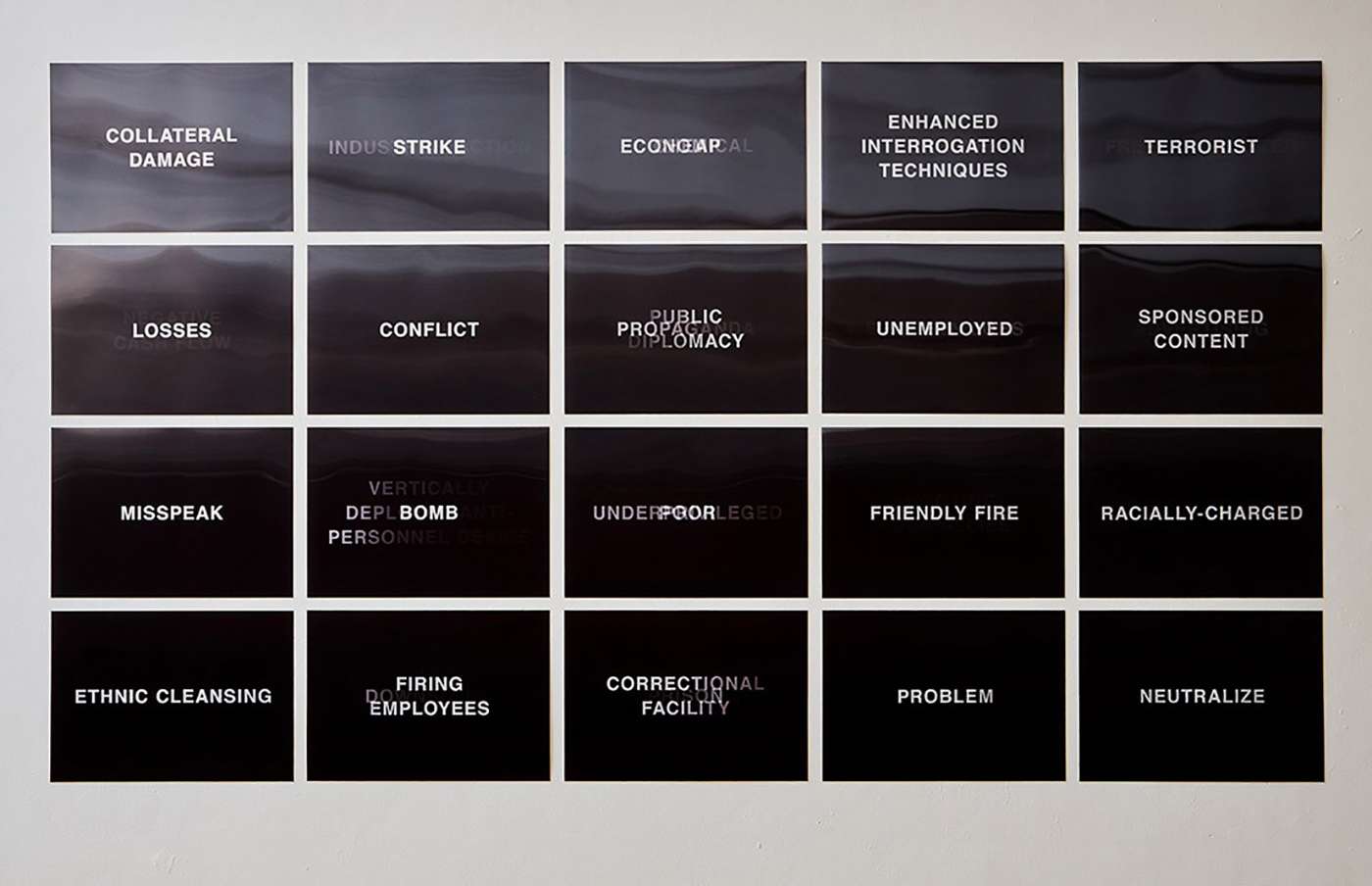

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

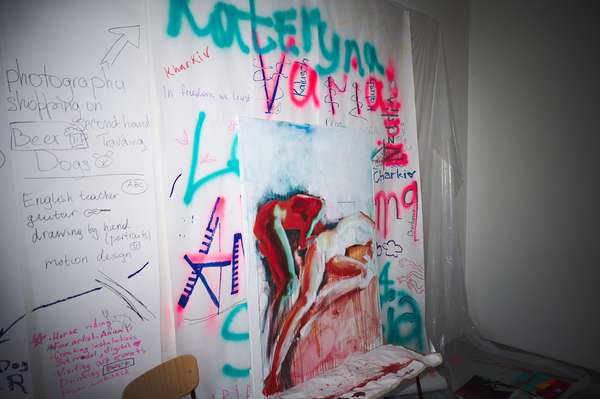

Kunst und Krieg

Kunst und Krieg

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

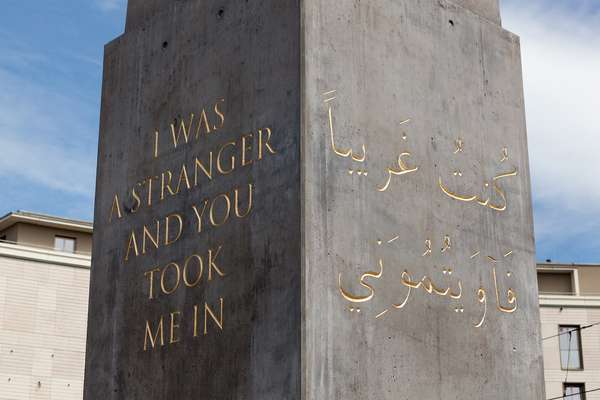

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

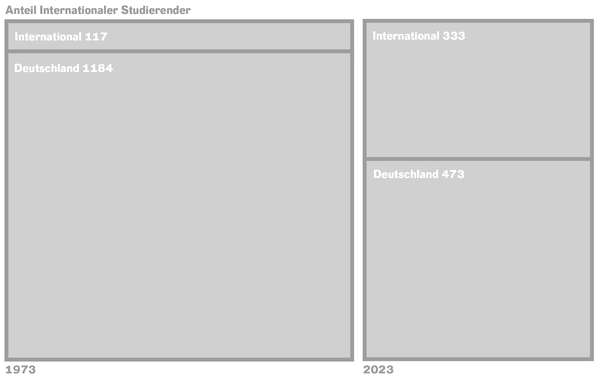

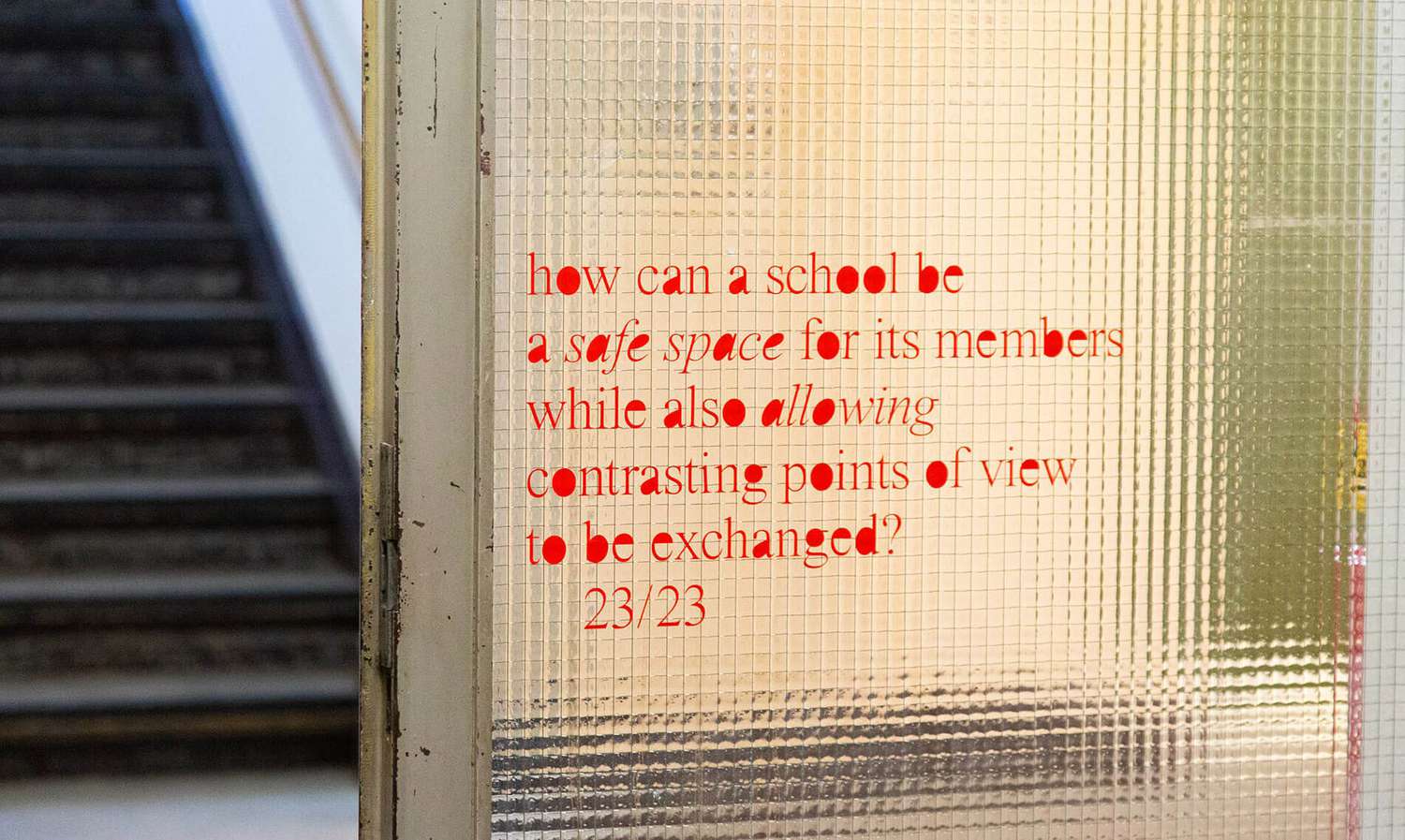

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

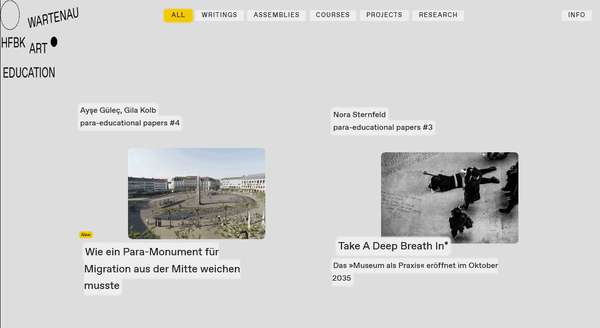

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

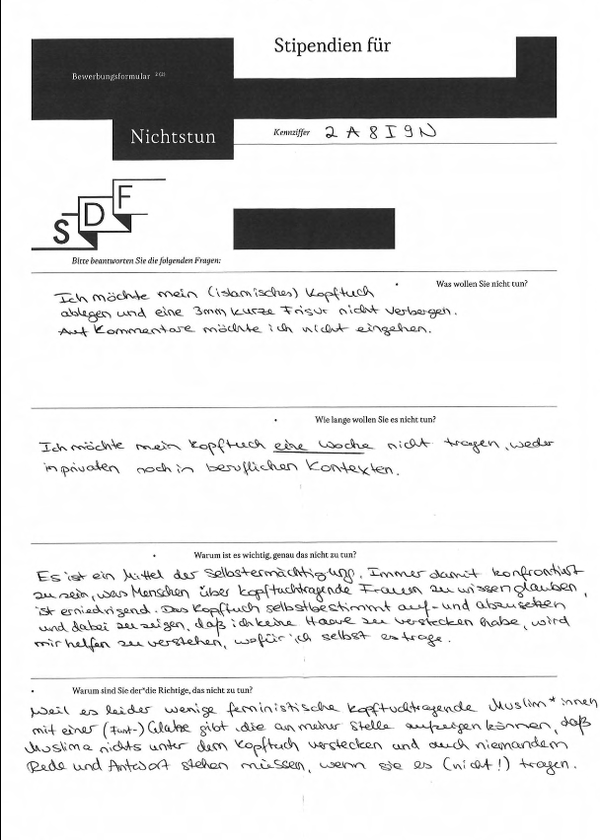

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

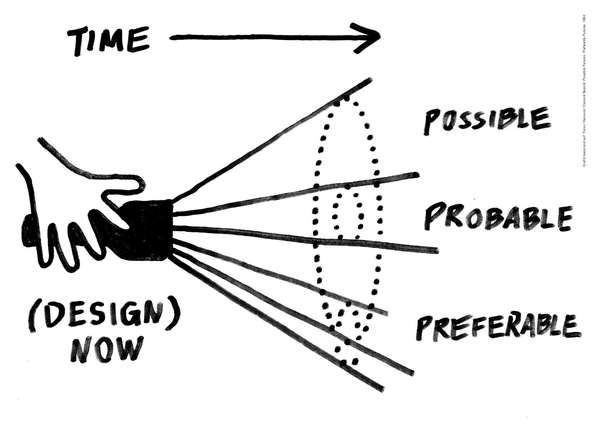

Wie politisch ist Social Design?

Wie politisch ist Social Design?