Lerchenfeld #52: Digital Thinking

Lerchenfeld spoke with HFBK-Professors Angela Bulloch, Thomas Demand, and Simon Denny about the influence of technology on their artistic practice and teaching digital culture to students of different generations

Lerchenfeld: What role does technology play in your own artistic work?

Angela Bulloch: I think first we have to define what you mean when you say “technology.” I think of it as a set of skills, or a method to achieve something like a scientific method or a process of making an artistic expression. It’s not just anything with LEDs on it. For example, the pen and ink have been and continue to be an important technology.

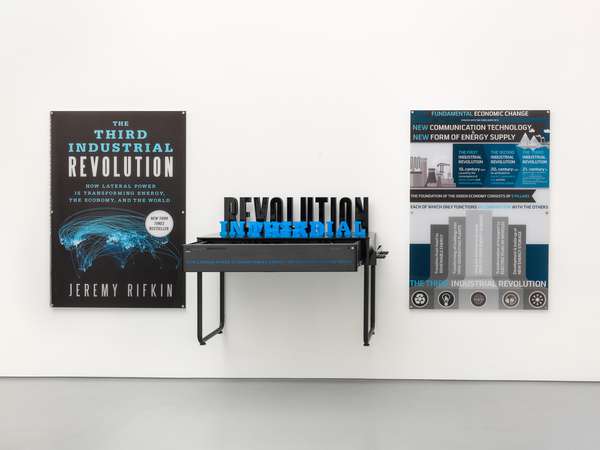

Simon Denny: I’ve come to see technology as a kind of encoded, technical politics. Processes, forms and tools that have an embedded infrastructure which is technical but also is political. Thinking about technology through this lens is part of my work—but potentially yours as well, Angela? Whether it’s a pen, ink, a piece of paper, or a hologram or whatever.

AB: Yes, I would say that you use technology to form a language. Technology is just a thing that you use for making your expression. I really started to make artwork in the late 1980s, and at the same time there was the beginning of the wide proliferation of the personal computer. There was an unfolding wave spreading across the world of very many people engaging with computers on a daily basis. So, for me, I was totally fascinated and set about getting to know computers. I was thinking about binary language, how to do programming and breaking the computer down into its constituent parts to find out what it is. How does it work? What can I do with it? My education in art and a specific interest in Minimal art brought me to questions about the materiality of a computer. Like with Carl Andre assembling works from regular plates of milled steel. The material aspect of computers was interesting for me. The silicon material at the core of every computer has gates or holes in the material, which are either open or closed. It is the structure of the material silicon that gives us binary language, which is the basis of the computers’ function. So I am from a time when computers were becoming popular elements that people worked with. For me it is important to think of how the material works, what the conditions or the qualities of this material are, what language they produce, what parameters the material itself gives us.

SD: I think I can relate to that as well, because when I really started to become active as an artist, I remember the moment as a student in Frankfurt actually. I started studying there in 2007, which was the year the iPhone was released. It was the start of the wide adoption of mobile and social computing and all the crazy stuff that came out of that. My friends and I were both bemused and intrigued and just wanted to get to know what was happening with the new possibilities of mobile and social as they proliferated. We couldn’t not follow it. It was a thing that was kind of at once so exciting and so scary and overwhelming. One could feel that this infrastructural change could be part of a big societal and cultural change, and so that was totally consuming for that moment.

Thomas Demand: I remember that moment as well, but I also remember that LG was a few months earlier with the touchscreen, the apps, and a radical reduction of buttons on their device. It was just plastic and not glass that made a difference. Clearly, the material culture of all Apple products is widely underestimated, but at the same time no one can overestimate the rhetorical power this company has achieved. So a South Korean company had no chance in 2007, and it hardly has much of one in 2020 either.

Lf.: Do you see the smartphone and the new possibilities coming out of it more as material or as a tool?

SD: Well, it’s kind of both those things and other things as well. It’s also a kind of relic of a system. That’s the way I see it.

AB: A tool, a method of process.

TD: Concerning technology, I think it’s clear to all of us what the question is about, even if questioning itself is already some sort of technology. It’s about the digital overwriting the manual, analogue way of realizing art. I think a repeating pattern in the industrialized markets of the last 100 years was always that new technology is rolling over the existing, pushing the artisanal out of business and occupying it until the next one is ploughing through town. The new is making the existing look old. As an artist I think it’s important to be able to look at all tools on the table, but often those aren’t accessible and many times they get in the hands of the entertainment industry (because of their market power) before artists can actually experiment with them. And then you end up not using new technology but Hollywood technology, or gaming technology, Instagram filters, etcetera. As Simon says, by then you have to deal with that cultural practice as much as using the technology itself by the time you have a hand on it.

Lf.: At the time when the computer became popular, it was certainly not easy to work with. What made it so attractive?

AB: It’s the extraordinary potential of the computer—what can we do with them?—that was interesting to me. The fact that everyone could have access to a computer or even have one at home, it was very exciting to think about what people would do with them. The computer is not just for writing letters and texts but for communicating directly by sending emails, and most importantly for research. The world is at your fingertips at the click of a mouse. This was also the moment that images and music became digital, so that they could be duplicated, shared, and distributed with emails or online. I think of it as a digital revolution that happened during the ’90s because of the proliferation of the personal computer.

SD: It’s artistic but also personal. My first laptop was a portal to the world. It was my way of understanding and learning language. It was my entertainment hub, at the same time as it was my educational tool and my artistic tool, and I thought, “Hmm, this thing is kind of part of everything that I do. What the hell is it?” And I think that was again the beginning of me seeing technology as something that touches the social and the political.

TD: For my practice it was an evolution of the photographic standards at the time when Photoshop came in, and it had an impact on the way we were working with it. We were able to make it useful in ways the fashion industry, for instance, didn’t. But there was a smell to it. I remember when Andreas Gursky admitted that he is altering the images as he likes with software. That was not taken well.

AB: One of the reasons why I moved to Berlin at the end of 1999 was to develop a module, a piece of technology that I could make artworks with. There were certain people and companies that made it possible for me to do that. I was building a giant Pixel Box in physical reality that could run a program that changed colors and connected with other Pixel Boxes which also followed the same program, which was held in a Black Box: the brain sends the program via a protocol to the slave modules, which then perform the program. I figured out which language or protocol to use for my purpose, and then I worked out a method of programming. I found a specific controller, a very stable computer to put the programs onto. It was a technological language to work with. Then I set about building the physical modules with three channels each—red, green, and blue—with the functional capability of changing color according to a script or program given to it.

Lf.: In this case, you acquired and implemented most of the work independently. But I can imagine that computer technology is becoming more and more complex to master in detail by yourself.

AB: Well, it’s best to break down the tasks: there’s hardware and certain software you might need, so there are different types of technologies to deal with. I’ve just spoken about the example of the Pixel Box, but with any project: do what you can yourself, and work with the best people you can find in each area. Of course, people don’t usually do all of the elements themselves, and neither did I.

Lf.: How about you?

SD: I rely on the skills of different kinds of people as well, not only people being focused on, let’s say, the technical craft from the very physical to the somewhat more ephemeral, but also the intellectual support of researchers helping me to understand the things that I’m looking at and broadening context. My practice is reliant on many others.

TD: Same with me. We use CAD quite regularly, and sometimes the machines can’t handle the output. So we wrote software ourselves, modified machinery, and so on. With my videos it’s just not thinkable to do it by myself. The same goes for architectural projects. And I learned that the best people are the ones with a certain curiosity, and they like the problems I bring to them. I believe they find them cute.

Lf.: To what extent must one understand new technologies in order to be able to criticize their use?

AB: You don’t have to know how to code to be critical of coding or things that are coded.

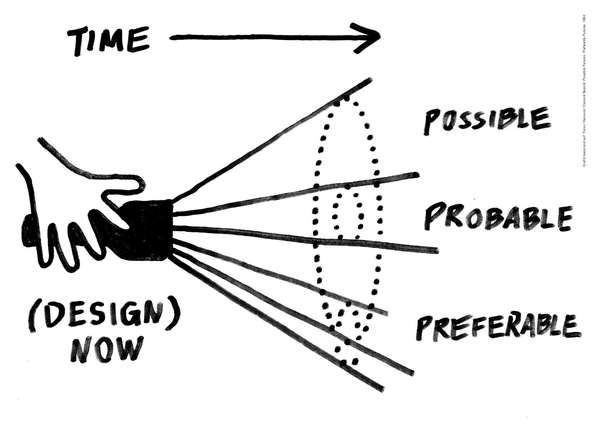

SD: I agree with that—but I also think the more you know about these processes, the more literate you are in understanding how these things work, the more precise one can be. So, I mean, I think as an artist I’m forever learning, forever trying to up-skill from the technical to the informational. And I am trying to encourage my students to be always up-skilling too.

TD: And not to forget that most of these tools are invented by human beings with a certain purpose in mind, and their imagination limits the possibilities in distinct ways. Especially with aesthetic software, you’ve got to keep in mind that the developer has inevitably outlined the claim in which this horse can be ridden.

Lf.: The author (and artist) James Bridle has an interesting analogy. When it comes to learning the technical tools, it’s like the painter who mixes his own paint. He has a fundamental understanding of the materials he works with and therefore can do more interesting and weird stuff with them. Does the comparison hold? What about conceptual art, then?

AB: If you’re in command of the language you are using, or whatever technology you’re using, then there is a better chance to be more articulate with that language. There will be potentially more time for thinking and doing things with the technology. Coding is really very much like knitting, because it’s really the position of the narrative sequence of things. You don’t have to know how to code to be critical of coding. It’s certainly possible to understand the effects of coding and say something about those effects without knowing how to code.

SD: Right, but if you do, you can make very articulate projects about particular things. Like a person who knows everything about pigments would produce a color which is amazing. But sometimes what’s important in an artwork is not getting the precise pigments. Many important paintings were made by people who have only basic skills in how to mix pigments.

Lf.: Do you see a difference between your views on computer technologies compared to your students, most of whom can probably be described as digital natives?

SD: It’s interesting for me to see the software paradigms that they follow and work in. Some of my older students have a maybe quite similar software paradigm compared to me in the sense of some programs they’re using and what they can do. But then my younger students—Generation Z-age students—they sometimes know different programs that became available more recently. I think they also differ in the general approach. I try to keep pace with the students. It’s great to get to know new software, and it can be very useful—but on the other hand, the paradigms shift quite quickly, and what was useful yesterday may not be useful today or even tomorrow. I think it’s important to keep a certain level of literacy and familiarity, while to specialize completely can also be a distraction. This is certainly the case with me. If I spend much time really understanding how to use certain software programs, I might become distracted from other things that are more important for me and my work. I think the one technology that is completely irreplaceable as an artist is how to relate to other people and how to communicate about what you’re doing. I think that this is one of the most important technological apparatuses that you can master, and I think if you become a communicator then all these other roles open up in a different way. This is definitely true for my practice and my understanding of anything technical: the first tool is social.

Lf.: Art increasingly takes place in virtual space. VR and AR works are concrete examples of this. How do you see these developments?

AB: VR is something that produces a lot of noise right now. There’s a lot of money being invested in the development of VR, but mostly for future use in industry. That doesn’t necessarily concern the art context, but it does concern the world itself, because it does shape what we’re going to experience. We’ll have more computers, more devices, and more ways of communicating with each other—whether it’s a navigational system or different ways of seeing the world we live in, and that does of course affect us as artists. So there are all kinds of developments in all sorts of directions and tools. There will be virtual places with a gazillion different layers and ramifications, possibilities, potentials, and it’s endless! VR is really a very specific and different way of visualizing spatial relations between the viewer and the fictional space. It doesn’t appeal to me greatly, as an artist, to work in that medium, but the spatial and perceptual aspects, how we see—that is interesting for me. I find it much more compelling to work with augmented reality (AR), because with AR you have a bit of “real reality” put into the virtual space, so that is a kind of interface between the normal reality and virtual reality. AR is much more interesting, from my point of view—than VR because I think that spatial fiction needs an attachment to an object or a piece of something real in order to appreciate the virtual.

SD: In the last semester we spent some time looking at Facebook’s communications, about their influence on VR. I don’t know if you saw the incredible promotional materials that they produced for their social VR platforms (Facebook Horizon). Believe it or not, within the Facebook VR platform, bodies appear without legs! It’s very bizarre—the people have no lower bodies. In my interpretation—and we had conversations about this in class—it’s a way for Facebook to maneuverer around the difficulties of representing the more physical and loaded indicators of gender. That means that certain representational problems are sort of avoided. And also the way that they imagine landscapes, space, and the way they present community—it all deserves a close read. There was an article in Wired which looked at something called the “Mirror World,” which is an analogy taken from a book by William Gibson, who first used the term “cyberspace,” and it’s now understood as a durable concept that has been applied to VR to map the size of the territory, perhaps even more granular. A piece of alternate fiction (Gibson’s novel Pattern Recognition) turns into reality. It will be possible to count every way you look, every moment you spend looking at a certain thing. You can quantify advertising in a whole different way. A scripted environment becomes far more valuable. So I think these are the things that excite me about VR.

TD: But if you look at what’s being done within the arts, the narratives we know don’t work anymore. So far it’s still nothing more than a gimmick and the structure of a discovery game. Also, editing is impossible, or, as in the VR project by Alejandro González Iñárritu (Carne y Arena, 2017). He tries to be politically concerned but ends up pasting over the unresolved joints with surrealism. Or look at Jeff Koons’s VR piece. It’s just the same kitsch he does in chrome. For me, at this point it is a great tool to try out the flow of a show or see a setting for a work before production, but not exactly the artwork itself yet.

Lf.: Will VR change the way we experience exhibitions? Do we still need to visit exhibitions at all, or will the art be directly brought into our living room on VR headsets?

SD: VR is a solo experience at the moment. Sometimes even video feels better as an individual viewer experience too. For me, there is a lot of video art that works better on the Internet than in an installation in an exhibition, and I think VR could be like that too. It’s a more solitary experience, and it’s hard to make it function well in a gallery. Lining up for a headset is boring. AR is different. This is something I’ve used in an exhibition at Mona in Tasmania. I made this AR work for the app that visitors to the museum use to navigate through the building and identify artworks. In my AR work you encounter an empty cage in one of the exhibition rooms, which is animated with a bird inside it if you engage in the AR layer through this app and an iOS device. The more people engage with the AR and point their smartphone camera over the cage, the more bird calls you can hear from all the devices at once, so you get a kind of flock of these birds. It’s quite interesting to just view people engaging with the experience even if you’re not involved in the experience yourself (which can be the opposite with VR). It’s funny because there are all these people looking at their phones and looking at this empty cage and all this birdsong, but no bird is visible unless you look through your own screen.

AB: VR is a solitary experience. I think there is a preference toward the collective experience of museums. We go to the museum to see an exhibition or to see a specific artwork. We’re used to seeing artworks in museums and galleries, and sharing that experience with others at the same time, experiencing an exhibition all together in the public realm. But because of the way that VR works, it breaks that experience of sharing at the same time, because you have to do it in such a solitary way, with your eyes covered in a headset. We are somewhat disabled and isolated by VR headsets. I think virtual reality will come to affect us in many different ways—in how we communicate or how we understand an experience. But just listening to this discussion about VR reminds me very much of what people said about the Sony Walkman. I remember very well the kind of excitement that people got when the Walkman came out. That was incredible. You could listen to your choice of music while playing golf or just walking down the street. So we’ll have to see how this enthusiasm pans out with VR. It seems like there is a gold fever for VR at the moment.

While I am less interested in VR, I am more interested in artificial intelligence, in looking at structures and patterns of behavior. Recently I was working with a company called DeepMind. I was invited to develop an art and architecture project. One of DeepMind’s areas of current research is to predict the way that certain proteins will fold. It’s an incredibly important area of research, because if you can accurately predict the way that any specific protein will fold, then you could potentially help avoid genetically inherited problems. You can really work on the structural, the building blocks, if you can predict how proteins fold. You know, the importance and ramifications of these predictions cannot be underestimated. That’s super interesting. DeepMind is trying to “solve intelligence”—that’s what they say. They’re really speaking in this way. Artificial intelligence is all about figuring out what happens within certain parameters, like in a game of chess: it’s between two players and it has a beginning and an end, two opponents with one winner at the end and many permutations of movements in between. AI tries to make a computer play chess as well or better than a human can. So this is a technology based on the understanding of behavior, which is very interesting but also potentially disastrous and dangerous. It’s not necessarily good—it depends on how you use it.

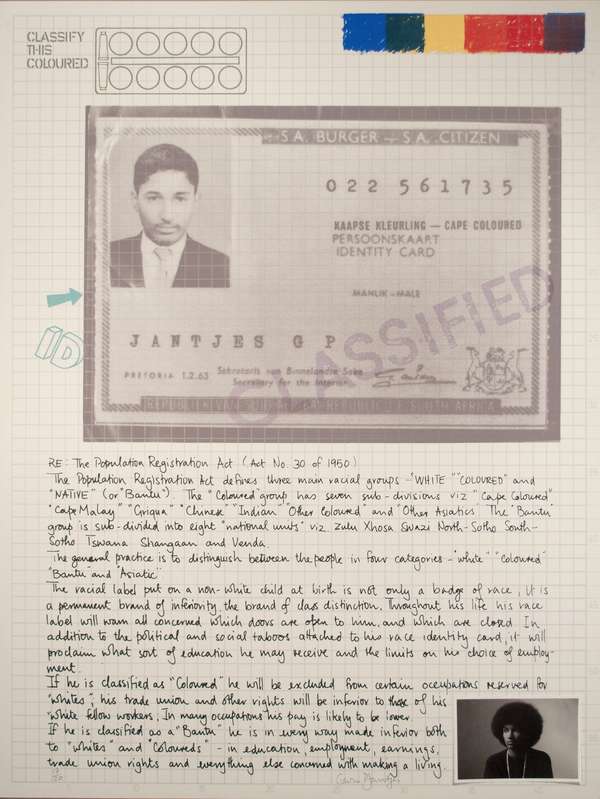

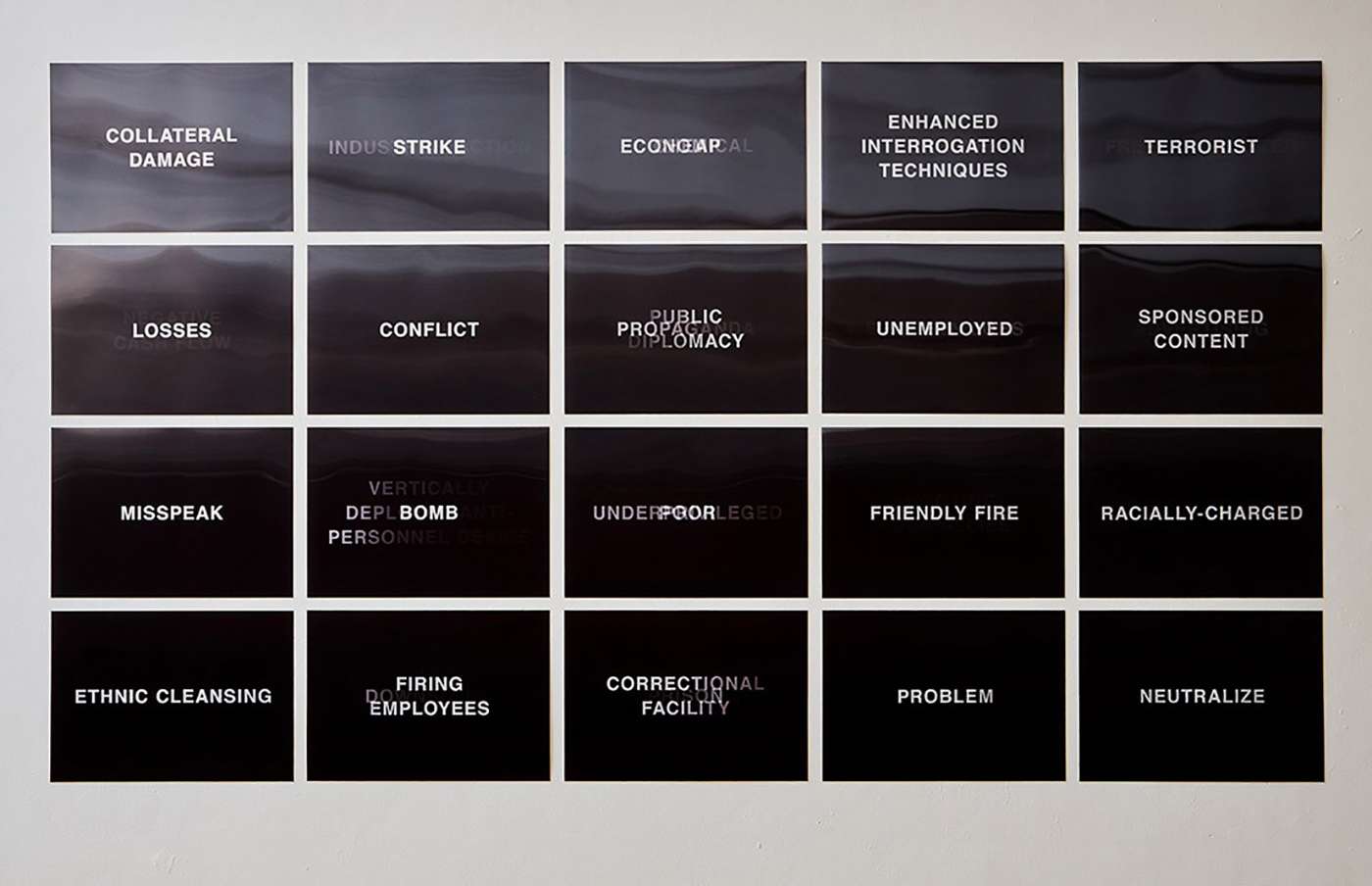

SD: This is something that has come up a lot in our class discussions as well. We focused on a project that’s currently on view at the Prada Foundation in Milan. Training Humans is conceived by Kate Crawford, an AI researcher, and the artist Trevor Paglen. It is a photography exhibition devoted to training images, the collections of photos used by scientists to train artificial intelligence systems to “see” and categorize the world. They reveal the evolution of training image sets from the 1960s to today. So they show all of kinds of images that were used in order to train machines. So what exactly are these kinds of artificial intelligence schemes being taught to see? And this is quite tragic, quite sterile. Because they follow very stereotypical assumptions about what the body looks like and what a face should look like, and there’s a large focus in their research on highlighting the biases that are in those training systems. There’s an amazing set that they pulled out. Up until the social Internet, training sets used images of people that were photographed often—mostly celebrities, because you need lots of faces of the same person. So often celebrities were training sets, and then this massive change happened. With mobile and the growing self-media you suddenly had all these user-generated images, millions and millions of them, so it’s not just famous people, it’s kind of everybody. But also what’s incredible is that they just scraped them (for example from Flickr accounts), and all of these images they used without any permission. It is interesting to see how we rely on these automated systems as a kind of “objective”, which is one major danger with AI. What we are relying on is something that is very limited and is framed by particular people.

AB: With particular biases.

SD: Yes, there are so many layers of political manipulation happening now. And it’s very interesting for artists to look into those questions.

Lf.: How should the school react to these new developments? Do you integrate new technical tools into the organization of your teaching?

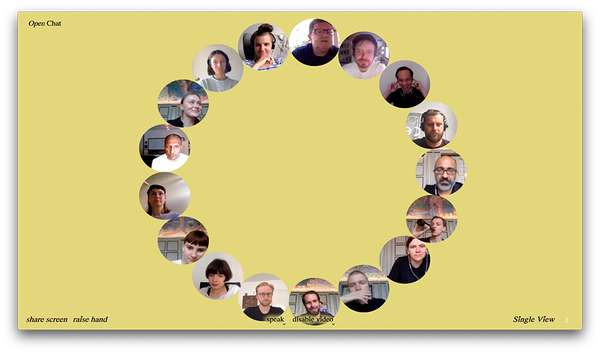

SD: I noticed a difference between the younger and the older students in my class in their research methods and how their attention works. I think that’s also coming out of the informational media environment, which encourages a certain type of fast looking, and I’ve tried to meet them halfway. I set up a Telegram group where I regularly post information. It’s a kind of a feed, and I find that very supportive. So if we have a guest, I’ll post all of the links he or she mentions during the talk. And in the end they’ll have all the materials compactly together and they’re very used to doing that. It’s on their mobile phone, not on the desktop. They can return to it at any time they want, and they’re used to the feed as a structural organizer. It naturalizes information in a different way. We call it the Bubble, because it’s like a little silo of shared knowledge. Sometimes it can actually be a positive thing to the class, like to focus on a similar set of reference points. I think, as critical as you can be with the mobile phone, the computer, and the Internet, there is truly a proliferation of access to information. I think my students read a lot. It’s maybe more about focusing on what one reads.

AB: And often it’s a question of being clear about the source: where does something come from? Who said this and why did they say it? We have to be vigilant about aspects of information when it is decontextualized. The Internet gives us great access to information. However, it’s important not to forget to question where the information comes from or the context of the information. We need to develop skills in terms of how to differentiate between information because information is not all relevant or interesting. It can even be propaganda.

SD: Indeed. And I think it’s great that the school has a kind of a curiosity for moving on to new programs and platforms. I think that’s a really positive thing.

AB: Yes, definitely, especially when it comes to 3D technology. That is important in the art context.

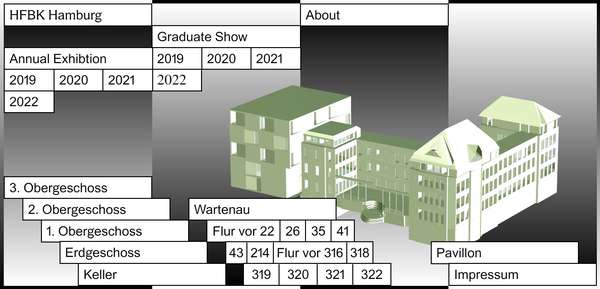

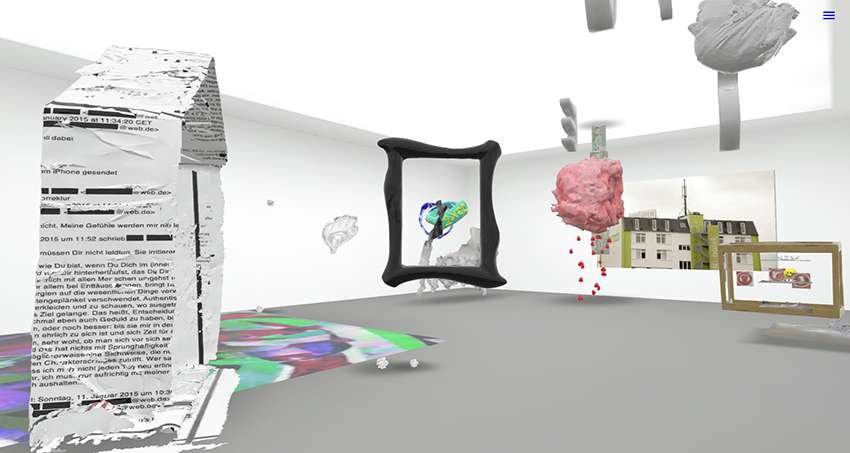

SD: I proposed that my students learn to produce their work in SketchUp so we can all put it in one giant SketchUp model of the room and look at it at the same time and move these things around, and that gives us more possibilities to organize and curate the annual exhibition, for example.

TD: We are putting a similar setup together too. It’s quite affordable now. However, I am not sure it nurtures a concentrated working environment. I think what’s not supported in all this is the thinking through doing, and the realization of an artwork with all its disappointments and shortcomings. It all looks just great on a screen, backlit, saturated, and shiny. I do believe though that we have a responsibility to instruct people to be independent in their practice and thinking, and that might mean way more than an educated use of technology.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

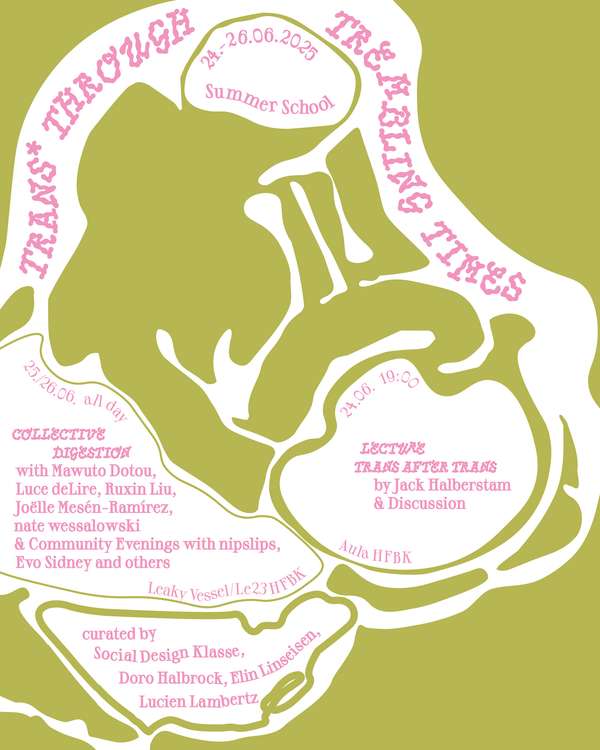

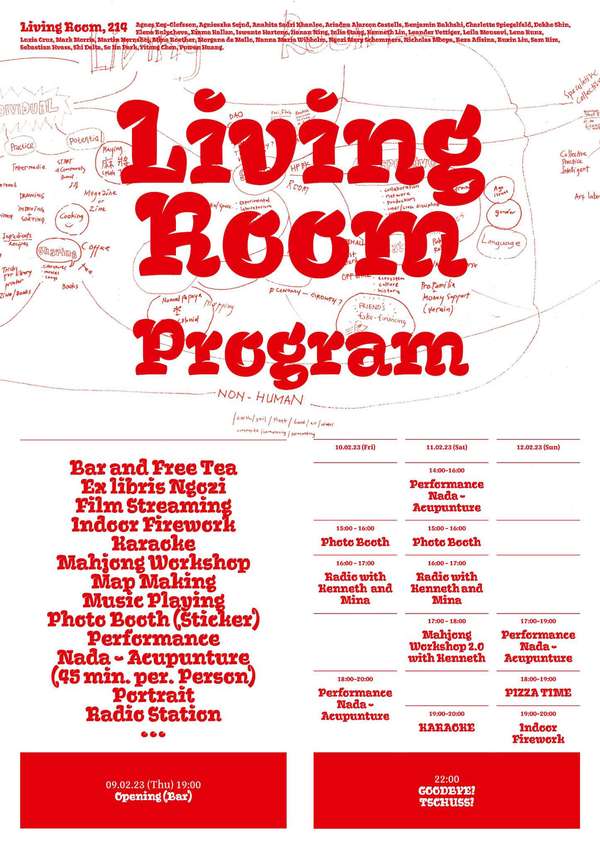

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

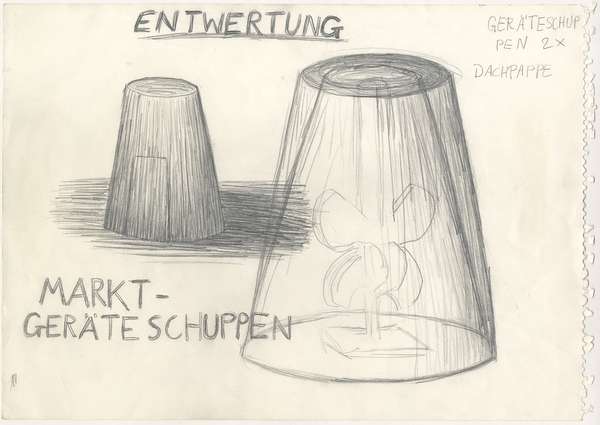

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Die Neue Frau

Die Neue Frau

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

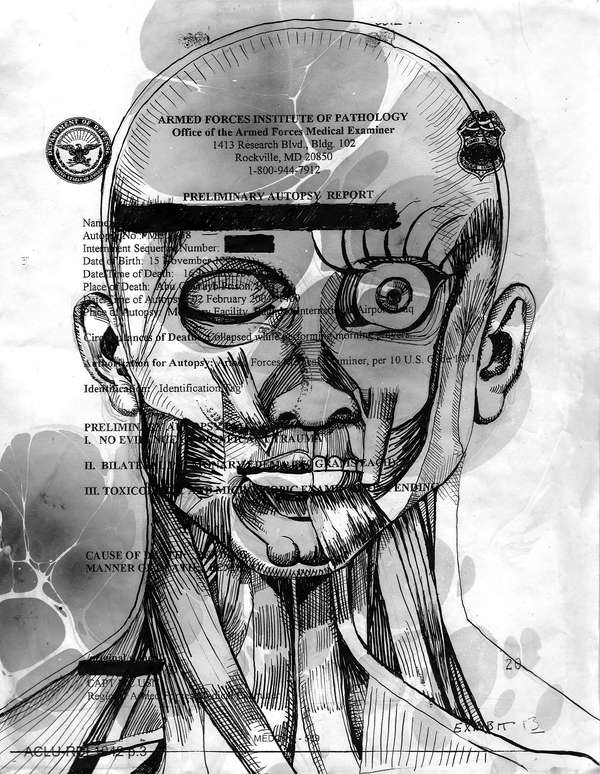

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

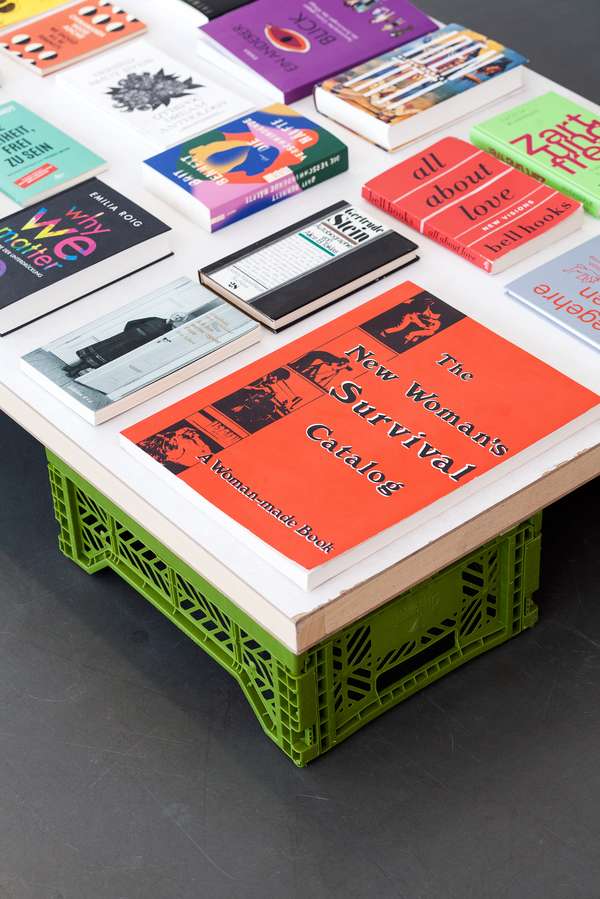

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

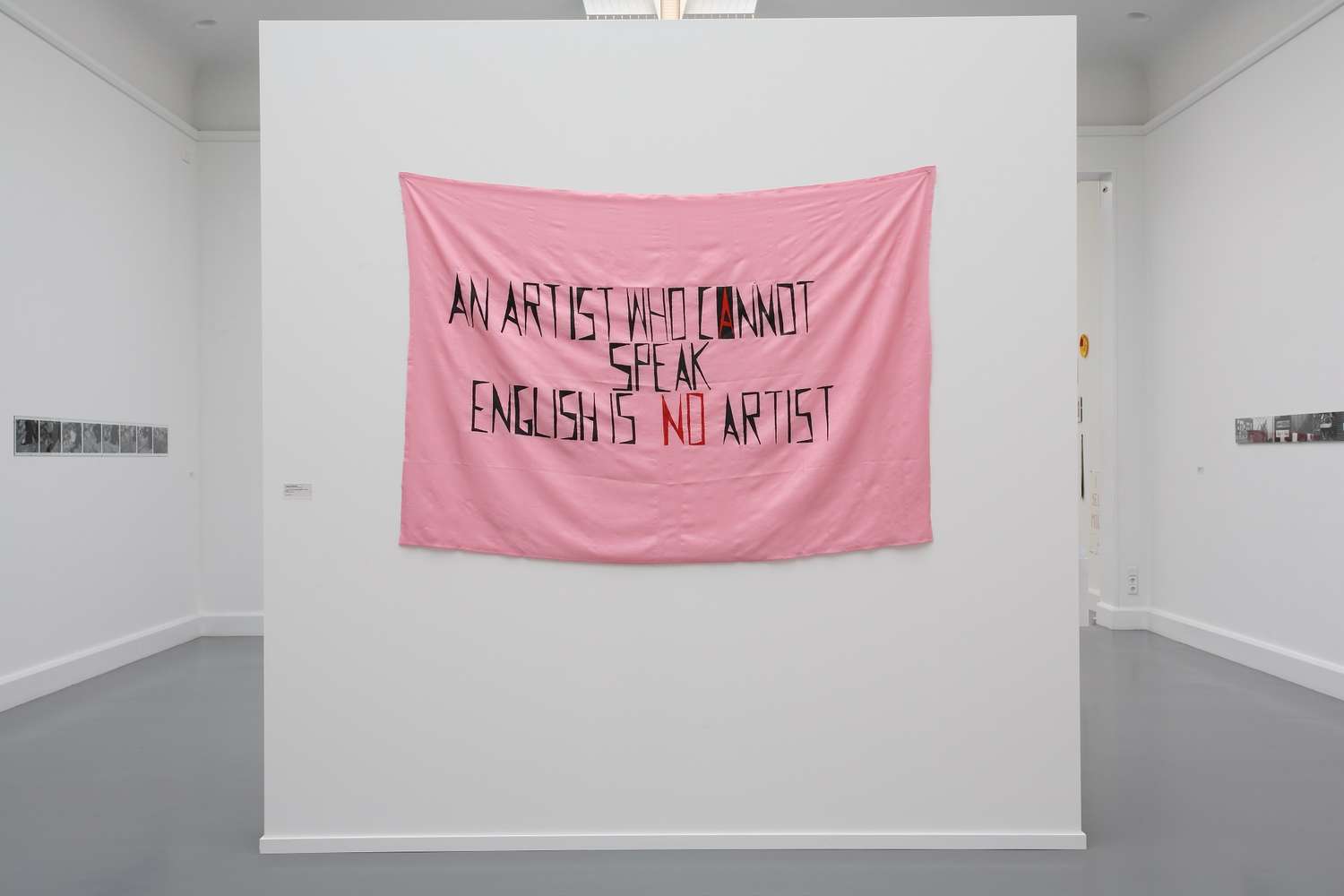

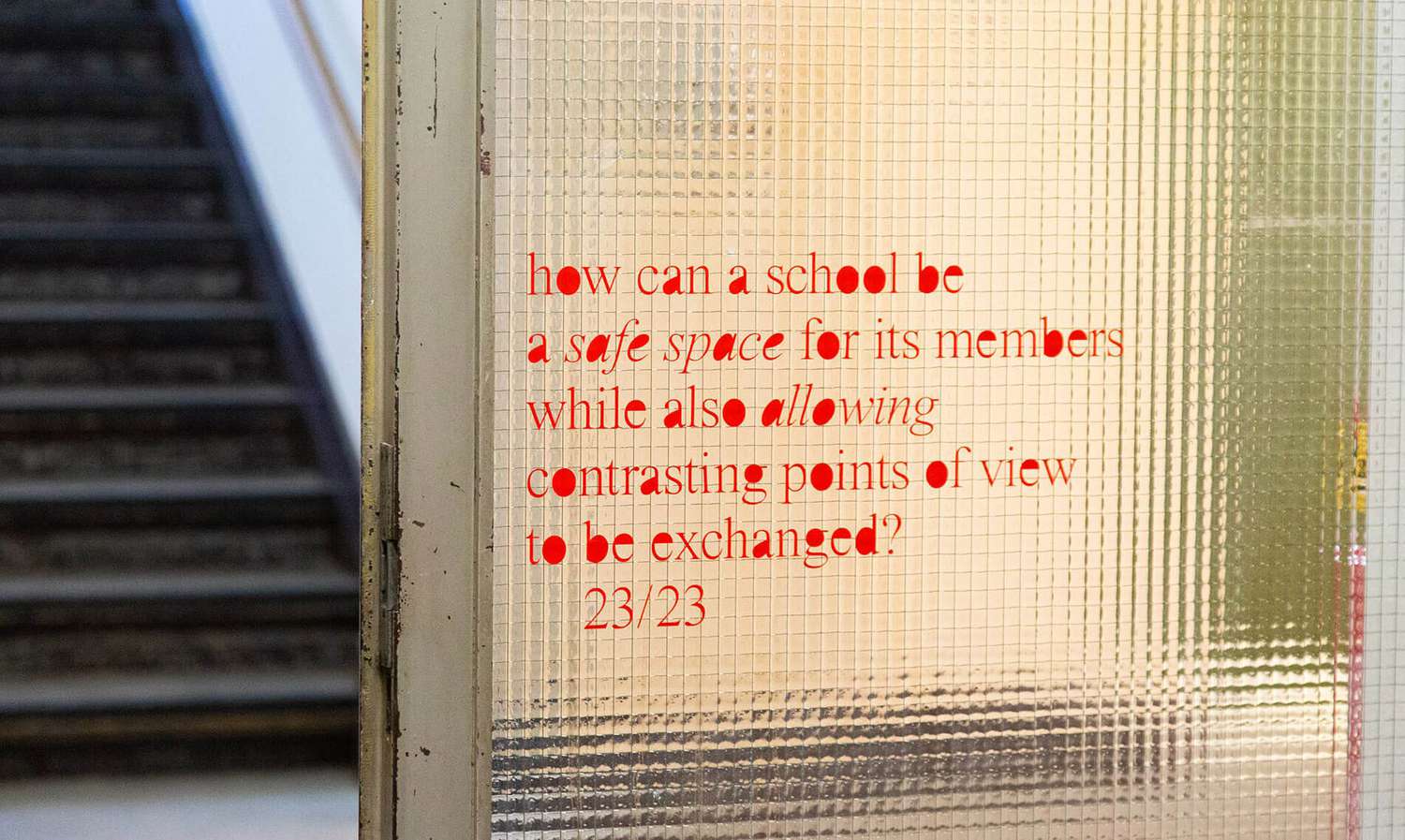

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Kunst und Krieg

Kunst und Krieg

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

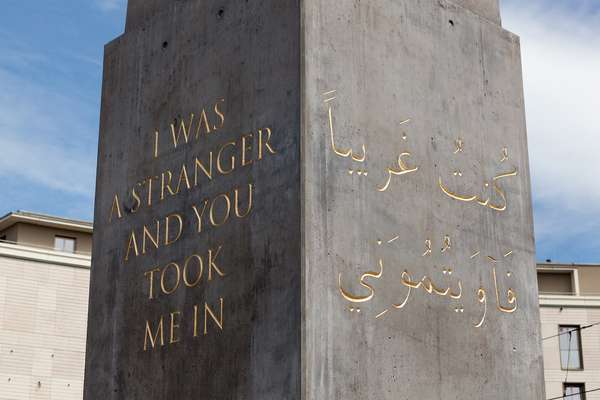

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

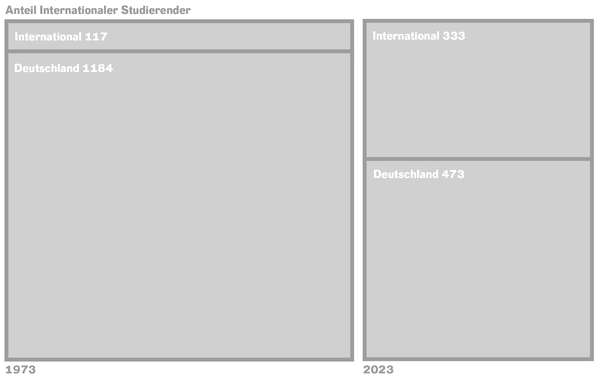

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Wie politisch ist Social Design?

Wie politisch ist Social Design?