Taking the different “Hamburgs” as a starting point

Beate Anspach: What is your understanding of public space? What characterizes a public space for you?

Joanna Warsza: For me public space is a place where we meet as human beings–and not only human beings–with and despite our differences. It is a place where we have to negotiate those differences. It's challenging, and art is a language that could help us with those complicated encounters. So that's one of the reasons I think it's important to deal with life in public space.

Nora Sternfeld: I couldn't agree more. And I think that in the moment we are in a complicated situation because what used to be public is more and more private, despite the fact that the public is very often mentioned in talks and discussions. We talk about “public programs”, “public events” and “public institutions”. But all these places become more and more precarious or private. And under these conditions, it is very important to think about what does public space mean today and what does it need to create that space between us in which we can negotiate. Behind this background it seems important to relate the question of the public with the question of the commons. Because in somehow neoliberalism managed to expropriate the public from “ownership”. That's why we don't even wonder that a public space can be private at the same time. This is a contradiction in itself, but we don't recognize the contradiction anymore. And when we bring the concept of the commons in, it becomes clear that we have to discuss again about the question of ownership. So, on the one hand, the public is about what is between us and what can occur as a possibility of conflict, but it is also the possibility to make things different. And on the other hand–when we think public space under aspects of the commons–it is also important to re-expropriate the private so that it becomes owned by everybody again. And when we talk about public space, historically, ownership was clearly related to it.

Joanna Warsza: I come from Eastern Europe, where there was a regime of communism, where everything was, in theory, public. And history shows us that the private space can become a political space of forging so-called public sphere. In the communist realm the streets were public, but in fact, they were, of course, monopolized by one ideology. So maybe, somebody's kitchen was much more of a public space than the streets. There is an own history of “apartment art” in various countries of the former Soviet Union for example. The distinction between the private and the public was not so much about ownership, as it was about the freedom of expression. It was about the values one wants to follow, it was about the public sphere, not only the concrete space. Maybe we have to differentiate between these two topics. There is public space. And of course, it's important to understand who it belongs to. But also, there is the public sphere as this arena in which we meet, including the digital sphere, of course.

Nora Sternfeld: And you are, of course, completely right. When we think about the history of the term, even in the sense of Jürgen Habermas, he explains how the public sphere started—it began as something clandestine. So yes, even before the coffeehouses, it emerged within these clandestine communities (“Tischgesellschaften”). Because in order for the public sphere to exist, it was essential to shift the perspective on truth somehow, away from the church and the nobles. This expropriation of the public can also be seen, for example, in the history of the museum. The Louvre would be a prime example of this—a place where objects that once belonged to the church, the nobles, and the king were made accessible to everyone. It became a space where the objects were counted as belonging to all. They have been reappropriated by the public. So, I think both perspectives are true. In order to re-appropriate the public, the clandestine aspect cannot be ignored. I completely agree. And unfortunately, in the world we live in, many things will still have to happen within quieter, and informal contexts so that other imaginations and possibilities for the commons can emerge.

Beate Anspach: I think the conflict between private and public space is also highly relevant to the specific situation in Hamburg. For instance, when you look at parts of the city, for example the Hafen-City, they often turn out to be private spaces in the end. This raises the ongoing question of how to use and deal with these private spaces, and how to transform them into a public sphere. What role can art play in this process?

Nora Sternfeld: I think it’s absolutely important to talk about this. It’s also crucial to discuss that double function that art in public spaces can have within neoliberal capitalism. Often, there’s an emphasis on imagination and big names being invited to projects, which end up contributing to the gentrification of cities. These projects attract tourism, and as a result, rents continue to rise higher and higher. Or we have another understanding that I would definitely opt for. Let’s take Park Fiction as an example. It represents a project by the people, standing against the forces of capitalization in a part of the city. This is part of the history of art in public space here in Hamburg: sharing the work and shaping the self-understanding of art in these contexts. Since the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, there has been a strong focus on creating counter-perspectives and counter-spaces within urban areas. So, I think there are essentially two options—and one of them is definitely the better choice.

Joanna Warsza: Maybe it’s because Hamburg, in the context of the German and European landscape, is a trade-oriented city. Perhaps the tension between private and public is necessary for something to be created. It’s also interesting to note that despite the heavy privatization and the ongoing development of Hafen-City with its constant construction, Hamburg is, the only major city in Germany that doesn’t have a Kunst am Bau-program (Percent for Art), like for example Munich. Whenever something is built in Munich, 1% of the budget is allocated for art. You could argue that this, of course, is part of the gentrification process, but these are still large budgets supporting artists. In contrast, as we know, in 1981, the city authorities in Hamburg decided to abandon the Kunst am Bau-program because they deemed it too conservative. I appreciate the vision that this city has forged for the understanding of art in public space with its experimental approach started in 1981 that the Stadtkuratorin position is also part of. But I am also wondering if artists could be more instrumental in building and expanding this city, so how to combine both. The ephemeral and the substantial?

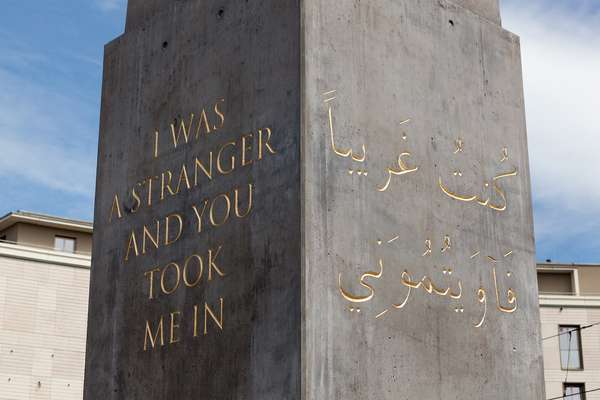

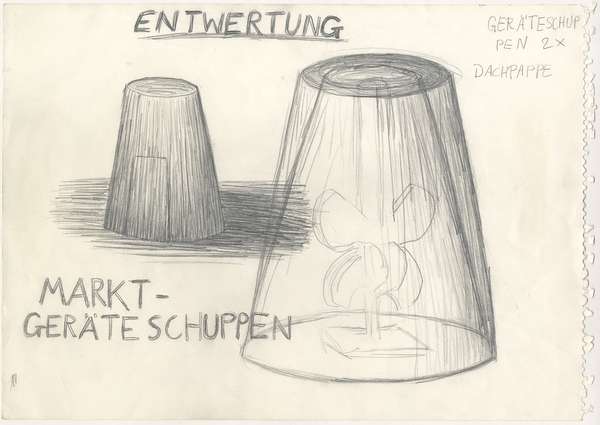

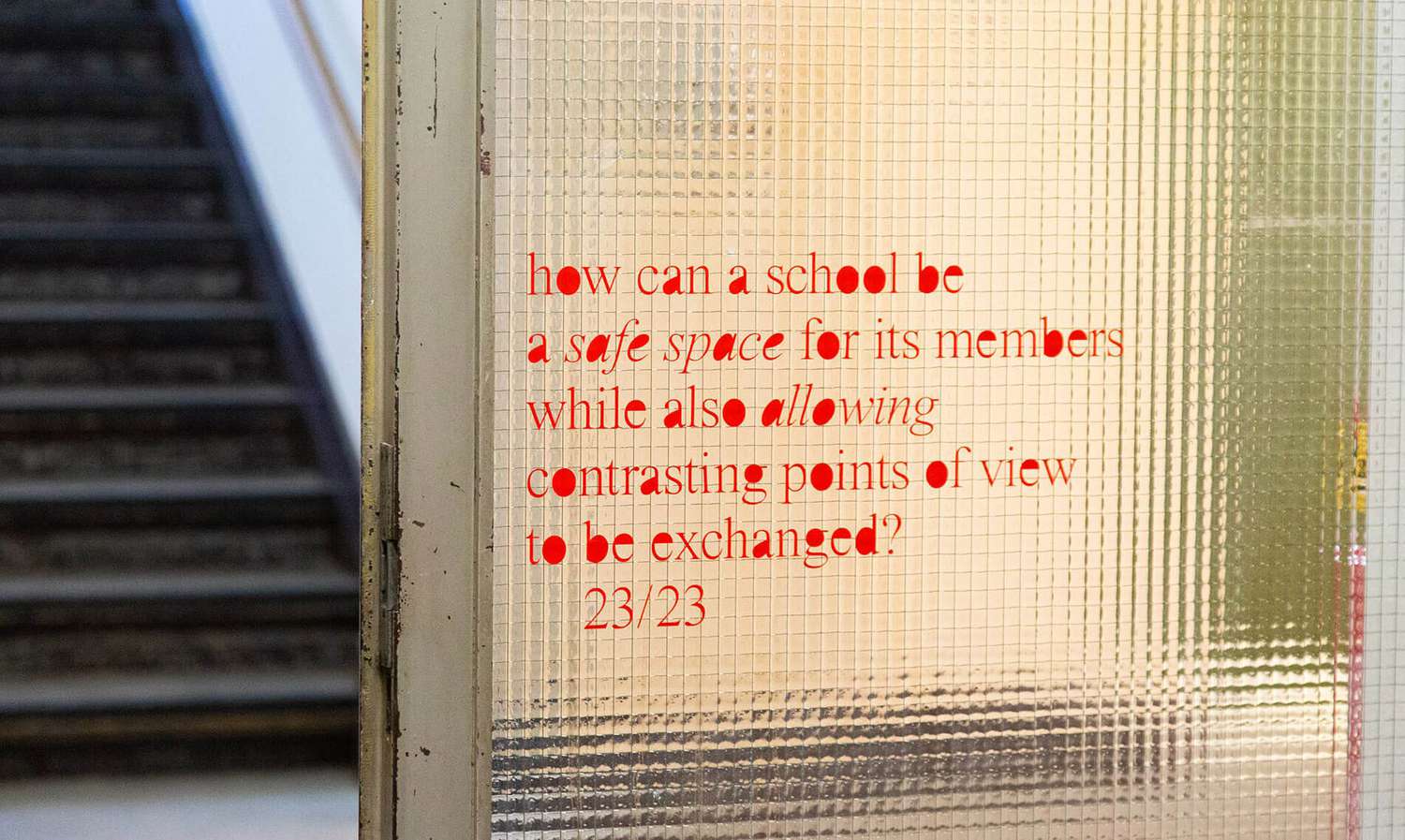

Nora Sternfeld: This semester, we are offering a joint seminar called “Monuments, Documents, Moments.” The title carries many references. One of them is actually the catalog Joanna created for her public art program in Munich, which documents the projects she did there. On the cover is a work by the Romanian artist Dan Perjovschi, who changed the word “Monuments” to “Moments.”. So, in between the monuments and the moments proposed in Joanna’s projects, we decided to include the word “documents”, because we are also very interested in the archive and the history of art and public space. We’re looking at the history together with the students, while also asking “How common is public art in Hamburg?” This question has two meanings. The first is: Who actually knows about it? We already realized that the students had no idea about the history of public art in Hamburg, which is a shame because it is, in fact, a very interesting history. The second meaning we discussed revolves around the public and the commons in the neoliberal cities we live in. To explore this history, we discussed a term that has been important in the last 20 or 30 years in relation to the history of monuments: the term “counter-monument.” We were fascinated to learn that the term counter-monument actually comes from Hamburg. It was used by the Kulturbehörde (Cultural Authority) and was related to the war monument near Dammtor, built in 1934 by Richard Kuöhl. In 1982, the city of Hamburg wanted to add an artistic comment with a critical perspective toward this war monument and they created a public open call for a so-called counter-monument[1]. Later, James Edward Young heard about it, became interested, and adopted the term when writing his important text on counter-monuments[2]. This means that the counter-monument, in a sense, is a contradiction in itself. But at the same time, it represents the city’s ability to allow something critical to emerge within its own means, which strikes me as quite democratic. It also shows the city's openness and pluralism.

Beate Anspach: When we look at the history, both in Hamburg and elsewhere, there has always been significant conflict over works in public space. Especially in the context of how to better mediate art in public space to the people. So, what do you take from your position as a mediator, in terms of learning from the history of conflicts surrounding public space?

Nora Sternfeld: For me, the bigger challenge in relation to the history of public art, is not that people hate it, but that people don't see it at all.

Beate Anspach: Like the Sol Lewitt work Black Form - Dedicated to the Missing Jews from 1989?

Nora Sternfeld: Yes, or the monument by Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz in Harburg, which is no longer visible. For me, this is the much bigger challenge. And it raises the more interesting question in relation to education. They have to be actualized. That’s why the moments are so important. It’s about the actualization. It’s about how collective memory functions. The fact that the monument by Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochen Gerz has been forgotten is also tied to what we’ve discussed before: privatization. The fact that we live in a place that, in some ways, is less public, but in other ways, we also live in times of great conflict. All of this is part of the educational relationship to art and public space.

Joanna Warsza: Monuments don’t remember anything by themselves. That’s what Michael Rothberg also said in his lecture in Hamburg at Kampnagel. It’s us who remember for them. In this sense, the actualization is so important. And, of course, who is that "we"? Because, obviously, many of these monuments were created in public spaces that are dominated by a singular, often masculine, understanding of space or by one dominant nationality. How can these monuments speak for post-migrants, and in what way? How do we do that? I think that’s also one of the themes for us, and for me as well.

Beate Anspach: I think this is an important point: Public Space is not inherently democratic. There are also fascist public spaces. So, how can we create spaces that address as many people as possible democratically? What role can art play?

Joanna Warsza: I think we're trying to prove that art can create these spaces, and in rare instances, it does. When it works, it really has a capacity building communities and giving an ontological shape to certain values. As curators and educators, that's part of our mission to believe in the agency of art. I will give you an example, last spring, I curated the project Radical Playgrounds: From Competition to Collaboration (together with Benjamin Foerster-Baldenius) at Gropius Bau in Berlin that functioned as a big playground—not just for children, but for adults too. It came from my own experience as a parent, often feeling bored at playgrounds and imagining them as potential sculpture parks with other meanings. It was for adults, for passersby, and for those who feel they don't belong in museums. It was like a parasite—something playful outside the serious institution. It was an experiment on how public space can be a place where we meet despite our differences. We were exploring pluralism, the tensions between the private and the public, and how they can play out in public spaces. When it works, it’s very rewarding and humanizing—it's where we connect through art, even beyond humans. It touches something basic, like the category of play. Play is a deep human need, and it transcends culture, it’s transnational. It’s not just games; it’s conversations, where there are rules, but we don’t know where they’ll lead. Finding common ground through play in public space is essential. Everyone, as human beings, relates to play. It can take many forms—game, flirtation, or more. In these polarized times, finding these common points is crucial. Air and water, for example, are common points that unite us. They are irreducible—they’re something we all need to survive, despite our differences.

Nora Sternfeld: I think, in some way, conflicts are crucial to developing a democratic understanding of the public. But this doesn’t mean that everything is possible, of course. It's also vital for a democratic understanding of the public to find ways to silence undemocratic voices. And this isn’t just about counter monuments. It's about making these things clear, creating a context of openness and debate that is able to close the doors to fascist and undemocratic understandings. This creates tension, but it's also a condition of possibility. Take the counter monument, for example. It’s not just about saying, “We live in pluralism.” That’s not the idea. It’s not just about presenting another possibility, but about creating a space that challenges the existing narrative.

Joanna Warsza: One interpretation of the word “performative” is that it creates an effect. It can be short-lived, and a revolution is short-lived, right? But it still has an effect. So, it’s performative both in its form and in its function, in its consequences.

Beate Anspach: We have talked a lot about historical positions and projects. What is your first impression of the current situation in Hamburg?

Joanna Warsza: More than in other European cities, I feel that Hamburg is made up of many different “Hamburgs.” For instance, in the station area, it can be a radical experience to be there at night. I was staying there for some time. Walking home, not feeling safe, really reminded me of how privileged we are in Europe to generally have safe public spaces. This area feels like a particular challenge to me, and it makes me think about what could potentially be done to improve it. I try to view it as an exercise in understanding public space. But then, you take a bike and within minutes, you’re in a wealthy neighborhood full of villas. And if you go to Park Fiction, you can see a completely different side of the city, one shaped by activism and resistance. It’s fascinating—but also a bit extreme—how you can experience such drastically different “Hamburgs” within just half an hour. And, of course, there’s the harbor, which is such a magnetic presence in the middle of it all. Living in a city where you have all of those tides—both the good and the bad, the high and the low—is incredibly striking and challenging. The history of Hamburg, shaped by trade and the global circulation of goods and ideas, has a complex, often exploitative legacy. Again, it’s a city of contrasts, the mix here is based on the difference. And it is a good starting point. Many Hamburgs to live and work with.

Joanna Warsza is the new City Curator (Stadtkuratorin) in Hamburg, she is a curator, editor, writer and educator. At the invitation of Nora Sternfeld she coruns the seminar “Monuments, Documents, Moments” at HFBK Hamburg. Her first exhibition project conceived for Hamburg From the Cosmos to the Commons, will open in the Planeatrium and the Stadtpark on the midsummer 21 June, 2025. https://www.stadtkuratorin-hamburg.de

Nora Sternfeld is an art educator and curator. Since 2020 she is professor of art education at the HFBK Hamburg. From 2018 to 2020 she was documenta professor at the Kunsthochschule Kassel. From 2012 to 2018 she was Professor of Curating and Mediating Art at Aalto University in Helsinki.

This text was first published in Lerchenfeld #73.

[1] The Vienna-based artist Alfred Hrdlicka's draft was selected from the open call, which was originally supposed to consist of four parts. In the end, two parts were realized. In November 2015, the deserter monument was inaugurated between the war memorial and the counter-memorial.

[2] James E. Young, “The Counter-Monument: Memory against Itself in Germany Today”, in: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 18, No. 2, The University of Chicago Press, 1992, pp. 267-296

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

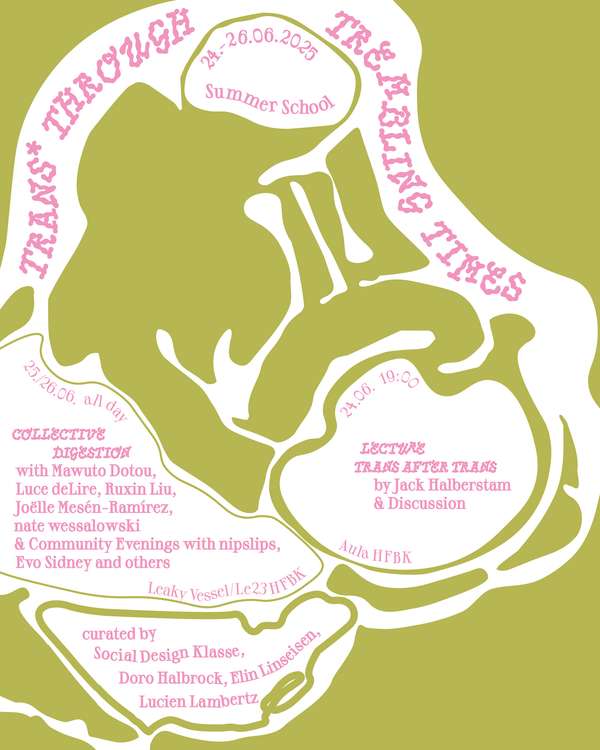

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

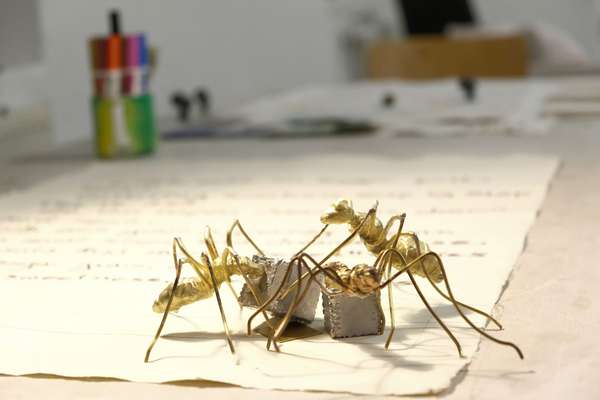

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

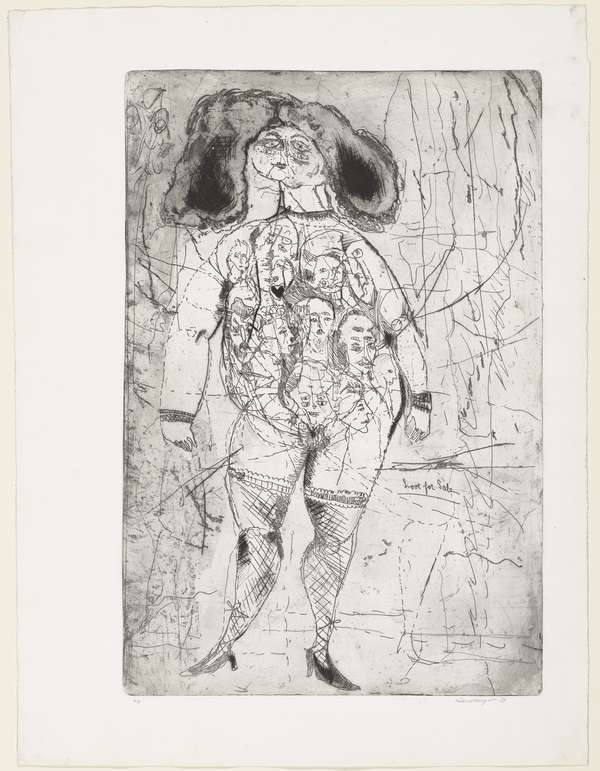

Die Neue Frau

Die Neue Frau

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

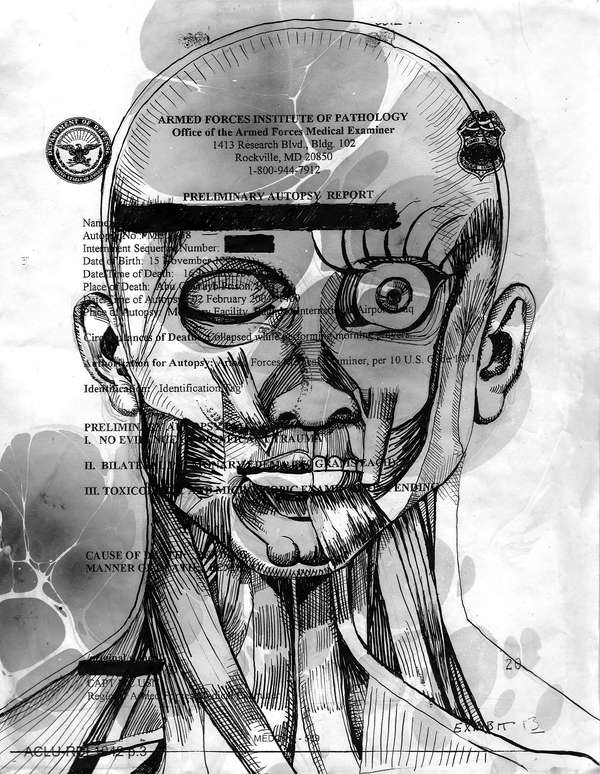

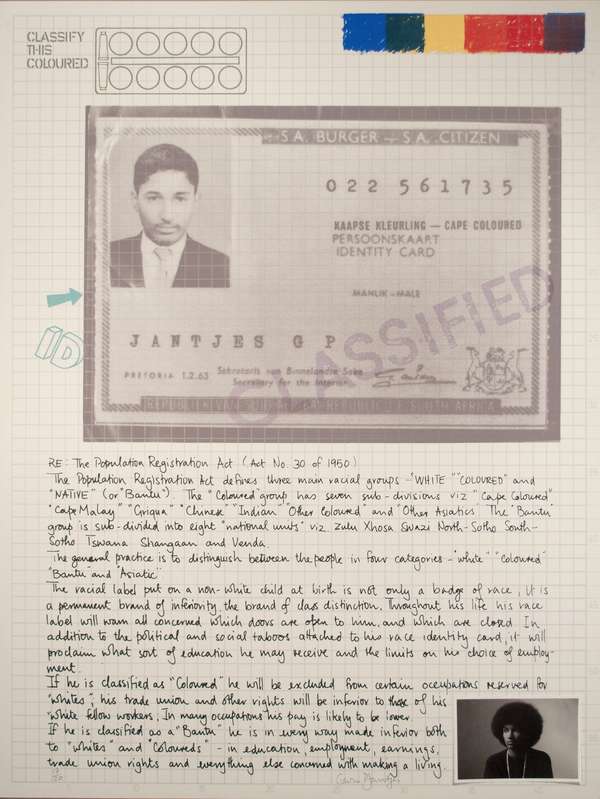

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

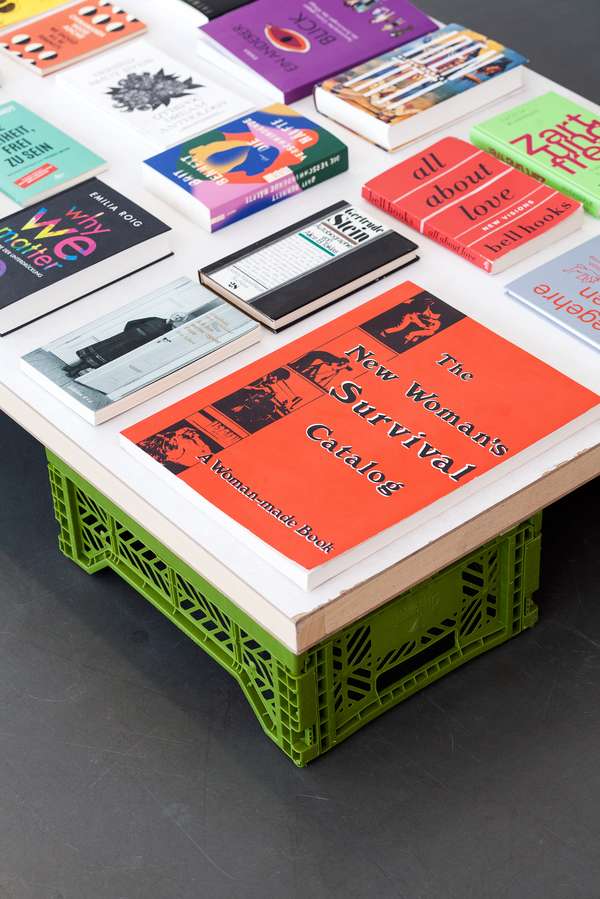

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

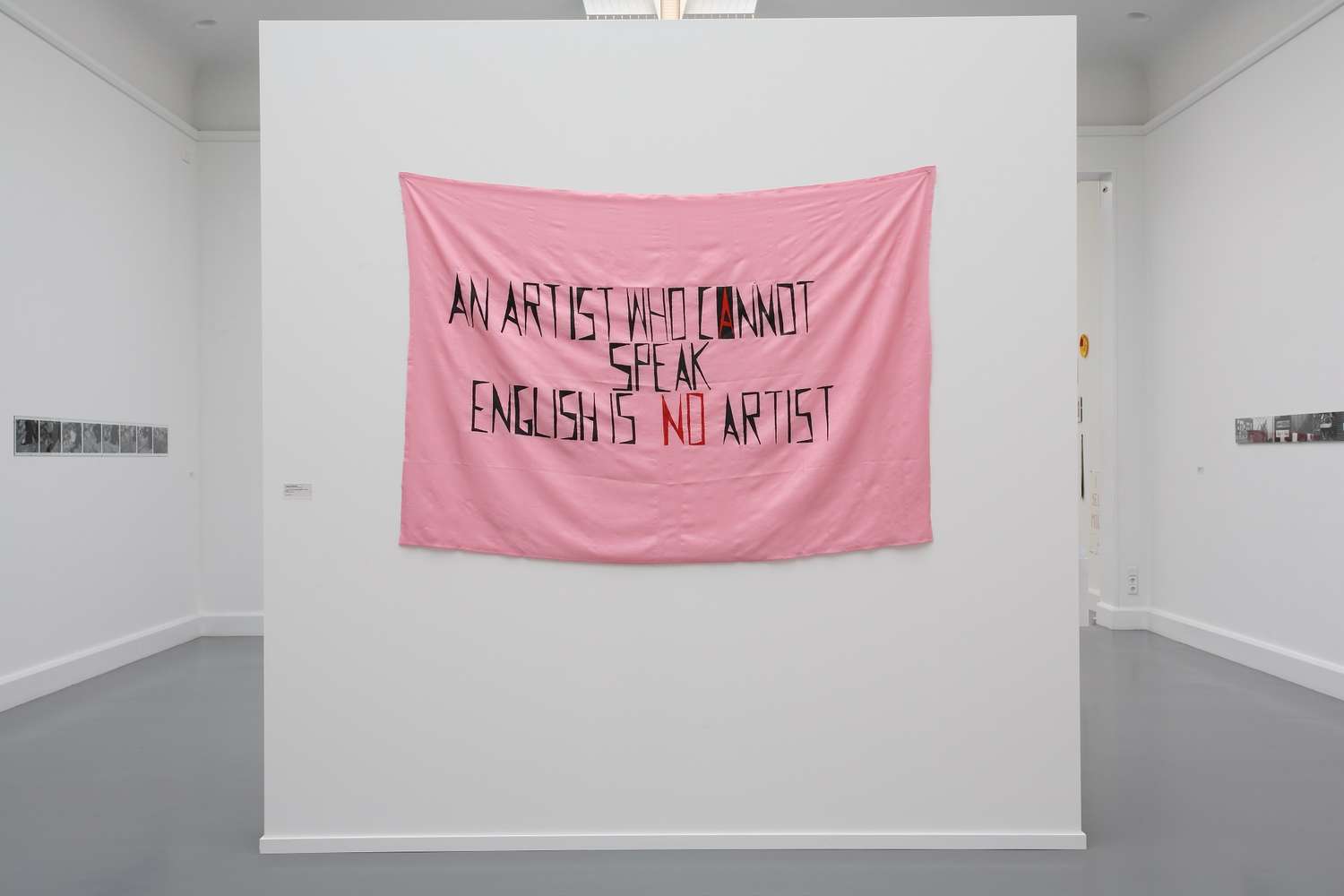

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

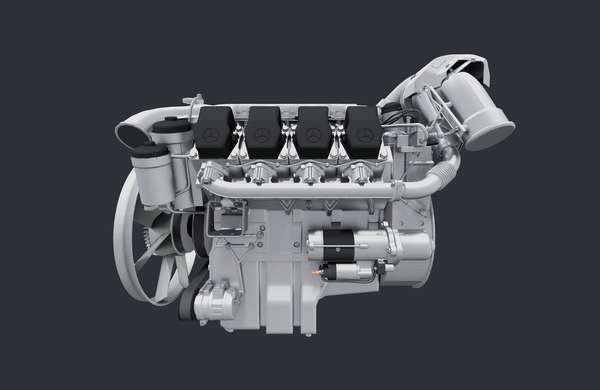

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

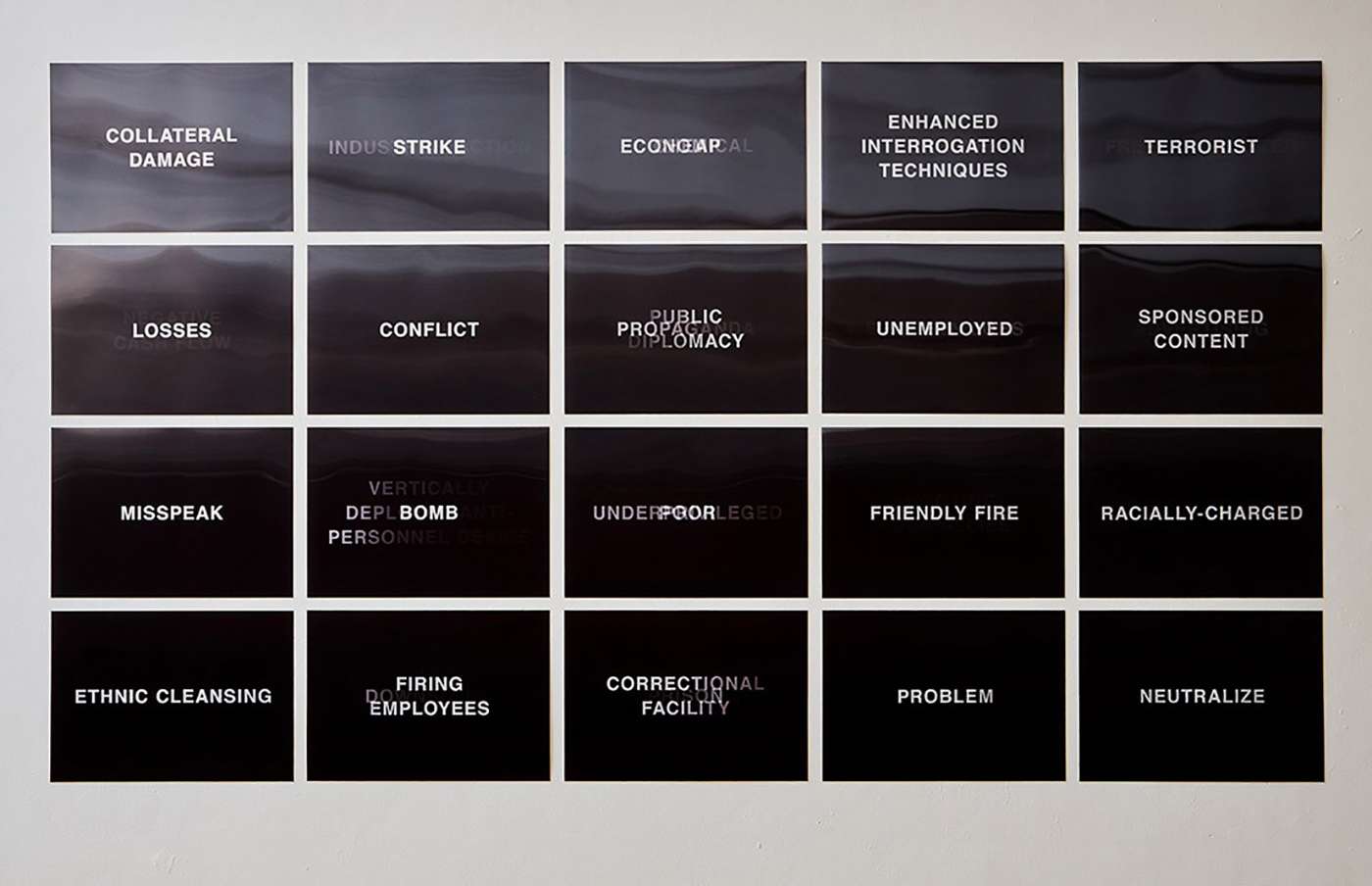

Kunst und Krieg

Kunst und Krieg

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

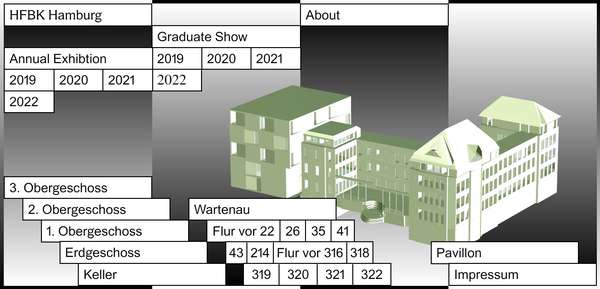

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

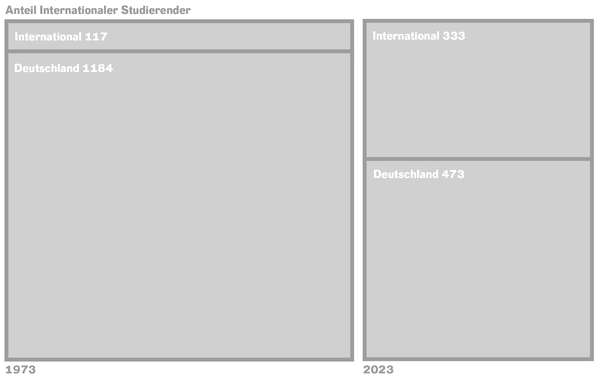

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

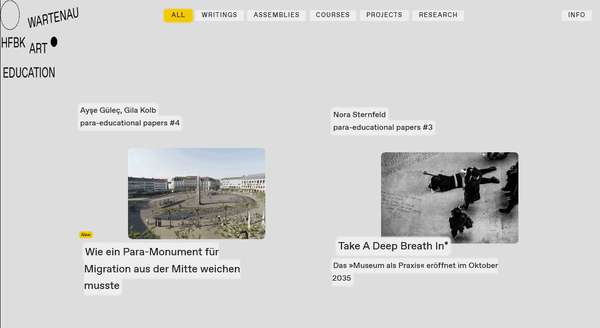

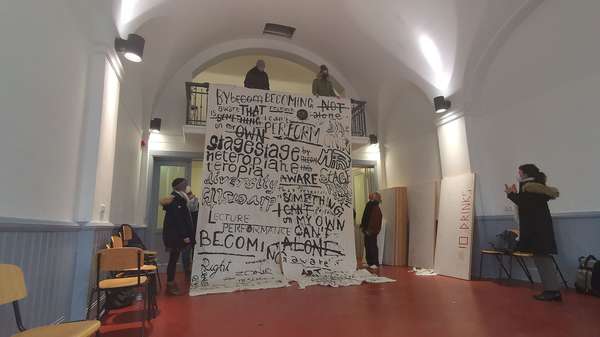

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

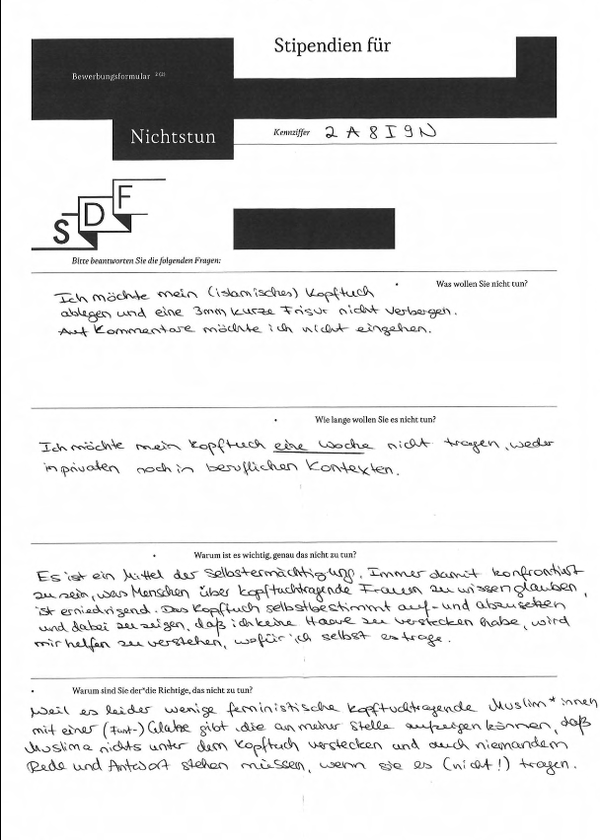

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

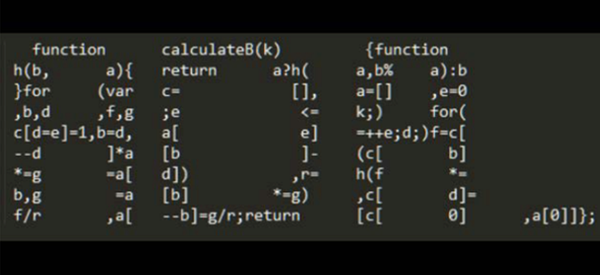

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

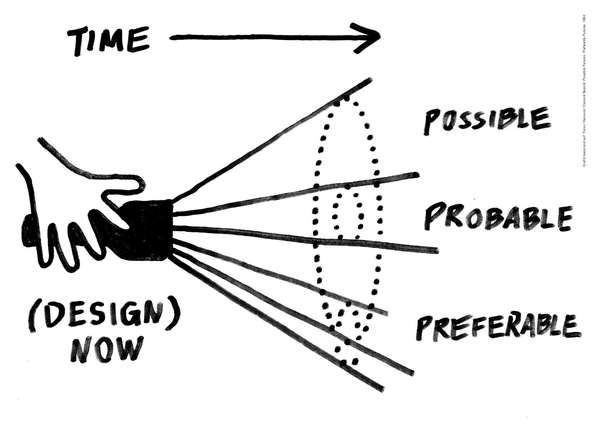

Wie politisch ist Social Design?

Wie politisch ist Social Design?