Corona Weltanschauung: Brief Reflection on Neoliberal Necropolitics and The State of Art

The pandemic provoked by the Covid-19 is a calamity that brings troubling questions about the passage of the human species on Earth. Even in the corporate media it has been said that the world will no longer be the same after the pandemic. On one hand, there is speculation about the emergence of a dystopian authoritarian world where life takes place in closed environments and human relations are reduced to online interaction monitored by the state / capital’s Big-Brother. On the other hand, it is stated, in a more hopeful way, that the crisis caused by the virus will make an anti-capitalist revolution without people once it reveals the contradiction and the perversion of the system. Following the futurological speculative debate on the media, Giorgio Agamben argues about the risk of the state of exception becoming the norm, while Slavoj Žižek reflects on the emergence of a humanist communism. In this same imaginative but more raw way of thinking, Byung-Chul Han states that China’s “success” in containing the virus will inspire the West to adopt forms of digital control similar to the ones the Communist Party of China has implemented. There is nothing really new on these speculations. The point is that while pop philosophers speculate about the future, life has been extinguished.

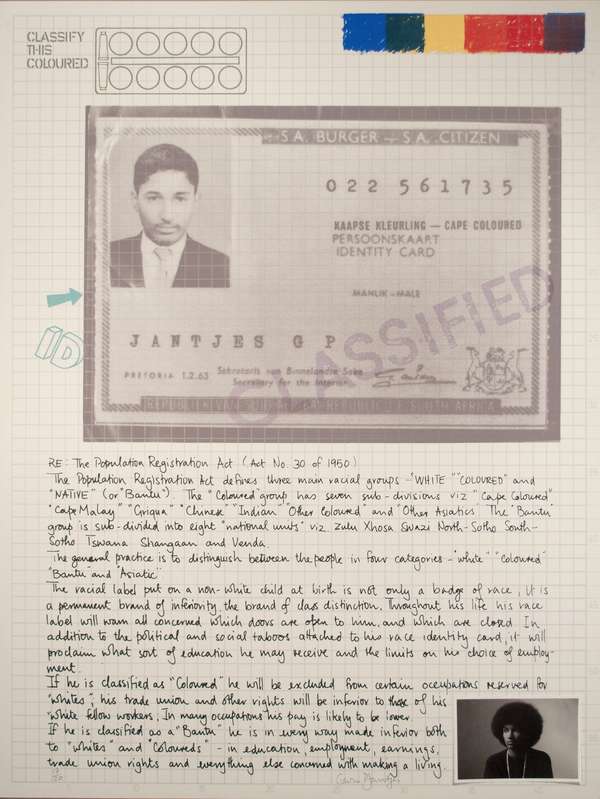

What everyone knows so far is that the lethality of the coronavirus makes it clear not only that neoliberal democracies are unprepared to deal with humanitarian crises, but also that there is an acute incompatibility between life and capitalism. In the past forty years, this system, especially in its neoliberal version, has intensively operated based on the assumption that one’s life is more worth than another. When analyzing neoliberalism, it is possible to go back in time and compare some of its main characteristics, especially competition and merit, with racist theories such as Herbert Spencer’s social Darwinism. According to Social Daewinism, social life naturally makes the strongest occupy a prominent place in society. Thus, the richest, so to speak, are the ones who survived and adapted, established themselves, in a model of life that is based on competition. The successful rich deserves by its own merit to take its place in society while those who are poor are poor because they were not able to triumph. When this theory is brought into the context of neoliberal social life, a highly competitive reality, even the death of people is naturalized. When a person fails, its failure is seen as its inability to adapt and to be useful to the system. It explains that those who have no practical value to the neoliberal system can be discarded. This logic of discarding “useless life” over “useful life” is, then, informed by idea that an individual must be productive for the functionality of the system. Therefore, it is no surprise that in the first weeks of the pandemic in the West Donald Trump, Boris Johnson and Jair Bolsonaro, main representatives of the far-right politics today, minimized the effects of the virus and adopted the idea of “vertical isolation”. An idea that claims for the isolation of the most fragile people to the virus, elderly people and persons with chronic diseases, while the most resistant ones, the youngest and most prone to work, continue to live and work “normally” maintaining the capital machine working.

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Graduate Show 2025: Don't stop me now

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Lange Tage, viel Programm

Cine*Ami*es

Cine*Ami*es

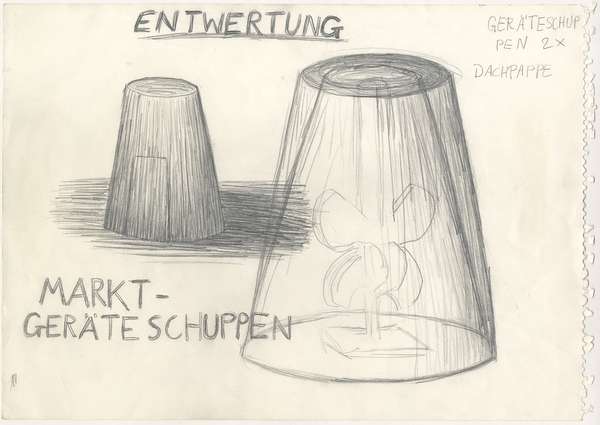

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Redesign Democracy – Wettbewerb zur Wahlurne der demokratischen Zukunft

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

Kunst im öffentlichen Raum

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

How to apply: Studium an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2025 an der HFBK Hamburg

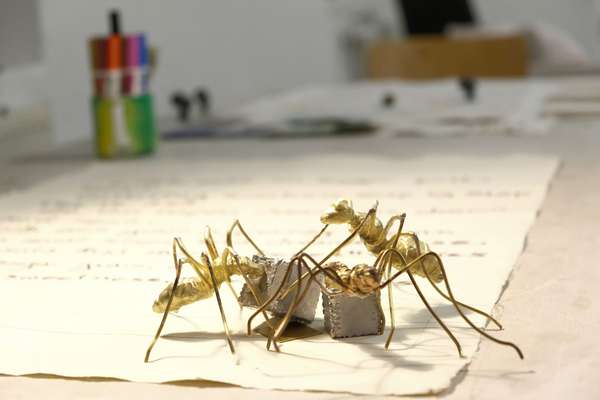

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Der Elefant im Raum – Skulptur heute

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

Hiscox Kunstpreis 2024

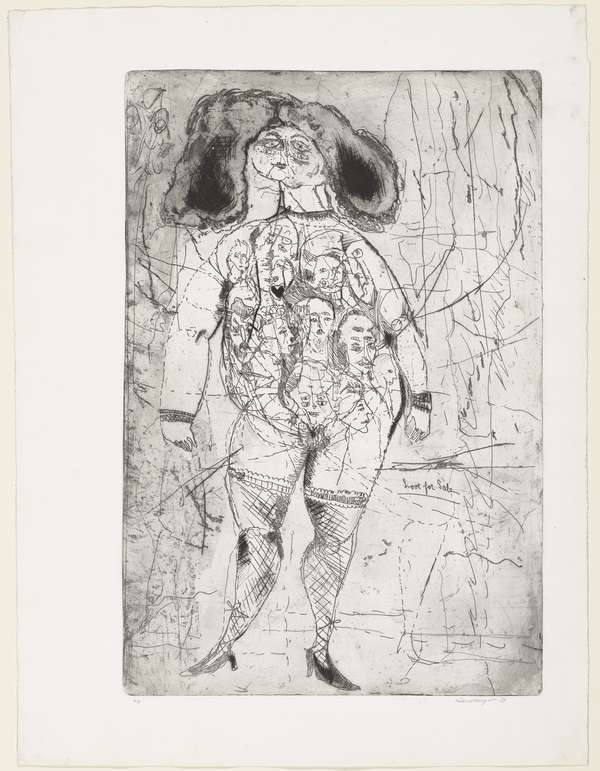

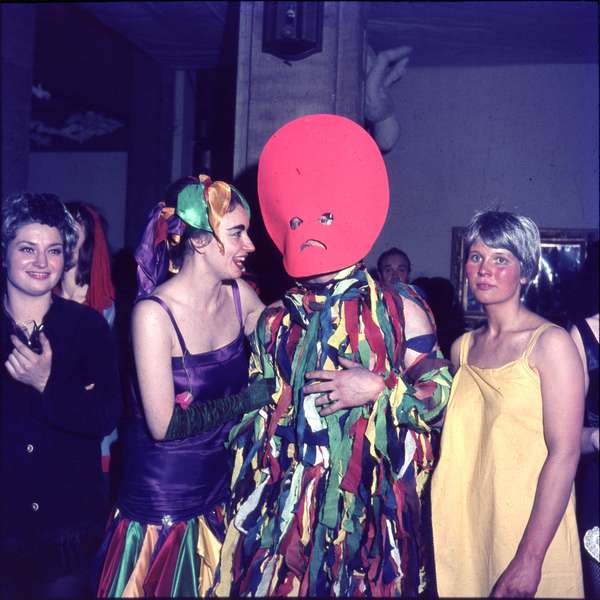

Die Neue Frau

Die Neue Frau

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Promovieren an der HFBK Hamburg

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Graduate Show 2024 - Letting Go

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2024

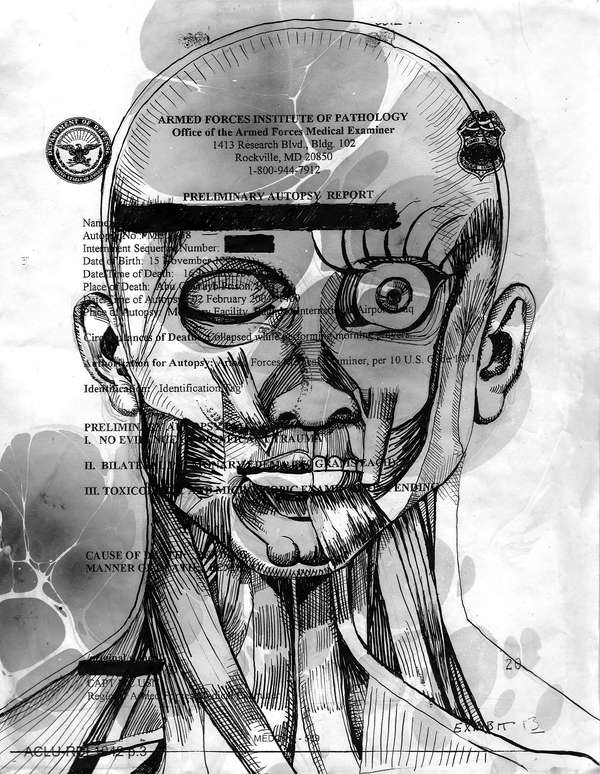

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Archives of the Body - The Body in Archiving

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

Neue Partnerschaft mit der School of Arts der University of Haifa

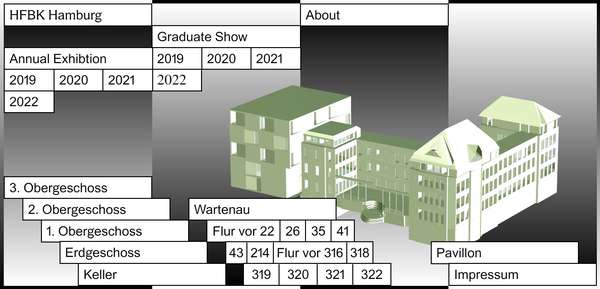

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2024 an der HFBK Hamburg

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

(Ex)Changes of / in Art

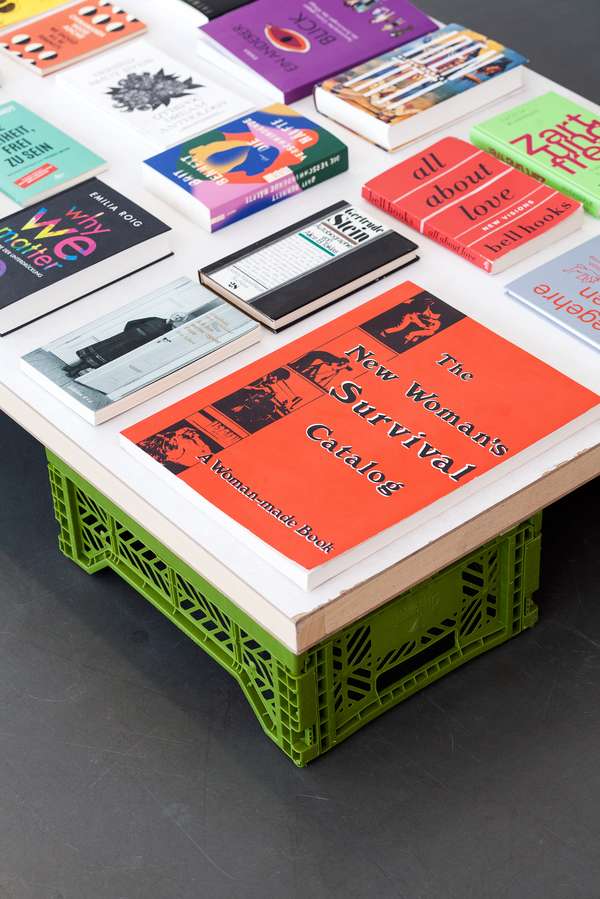

Extended Libraries

Extended Libraries

And Still I Rise

And Still I Rise

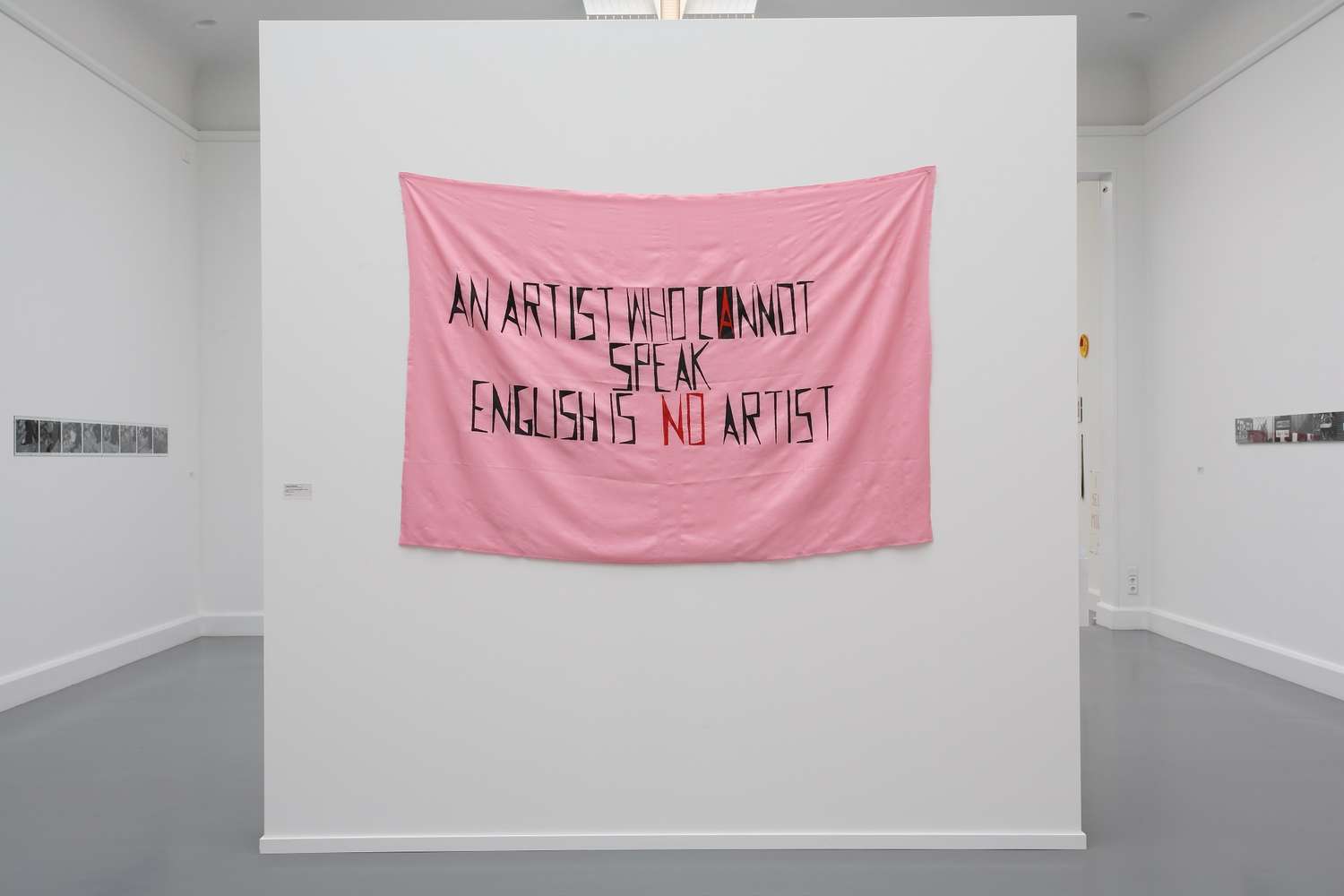

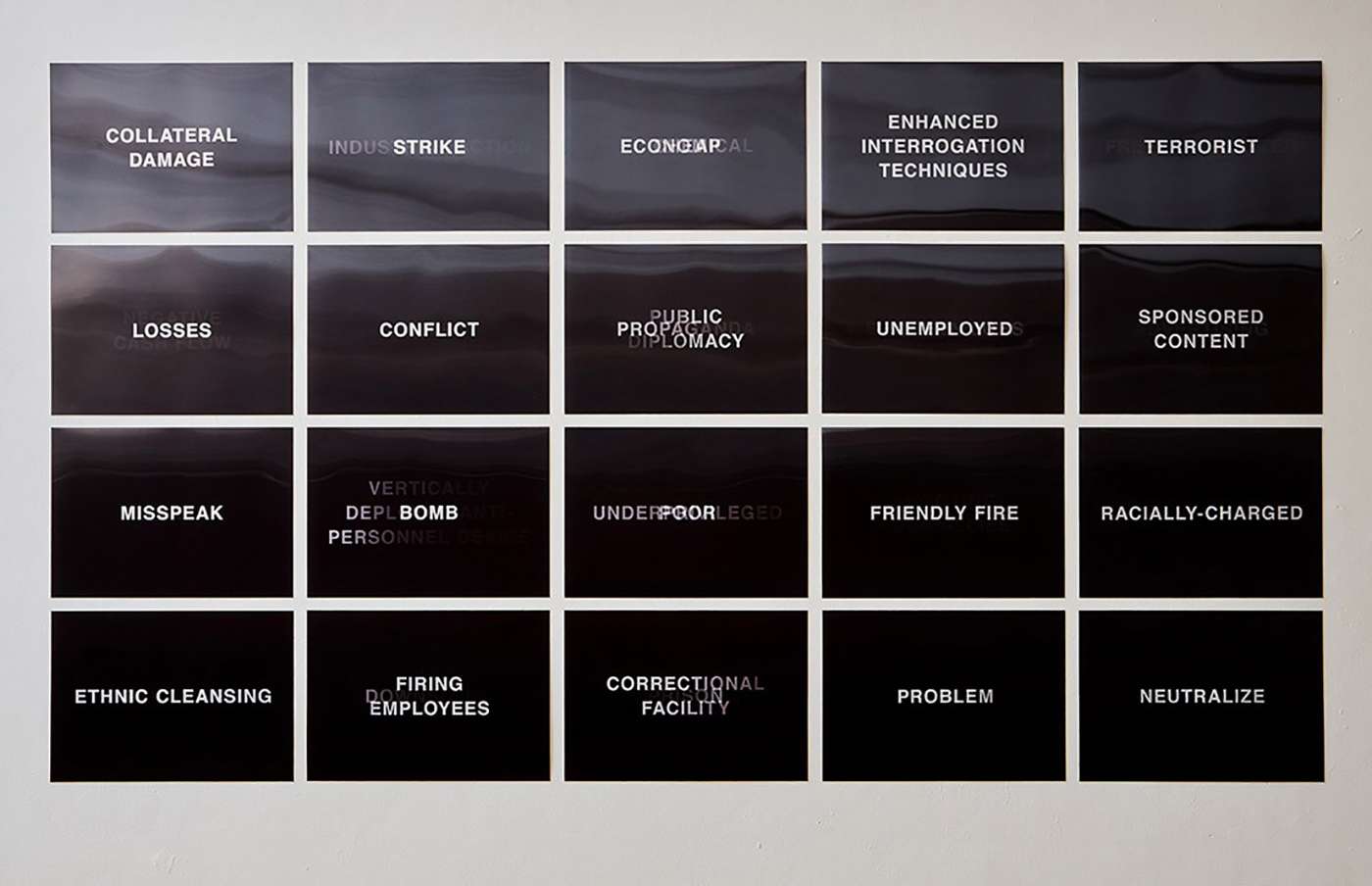

Let's talk about language

Let's talk about language

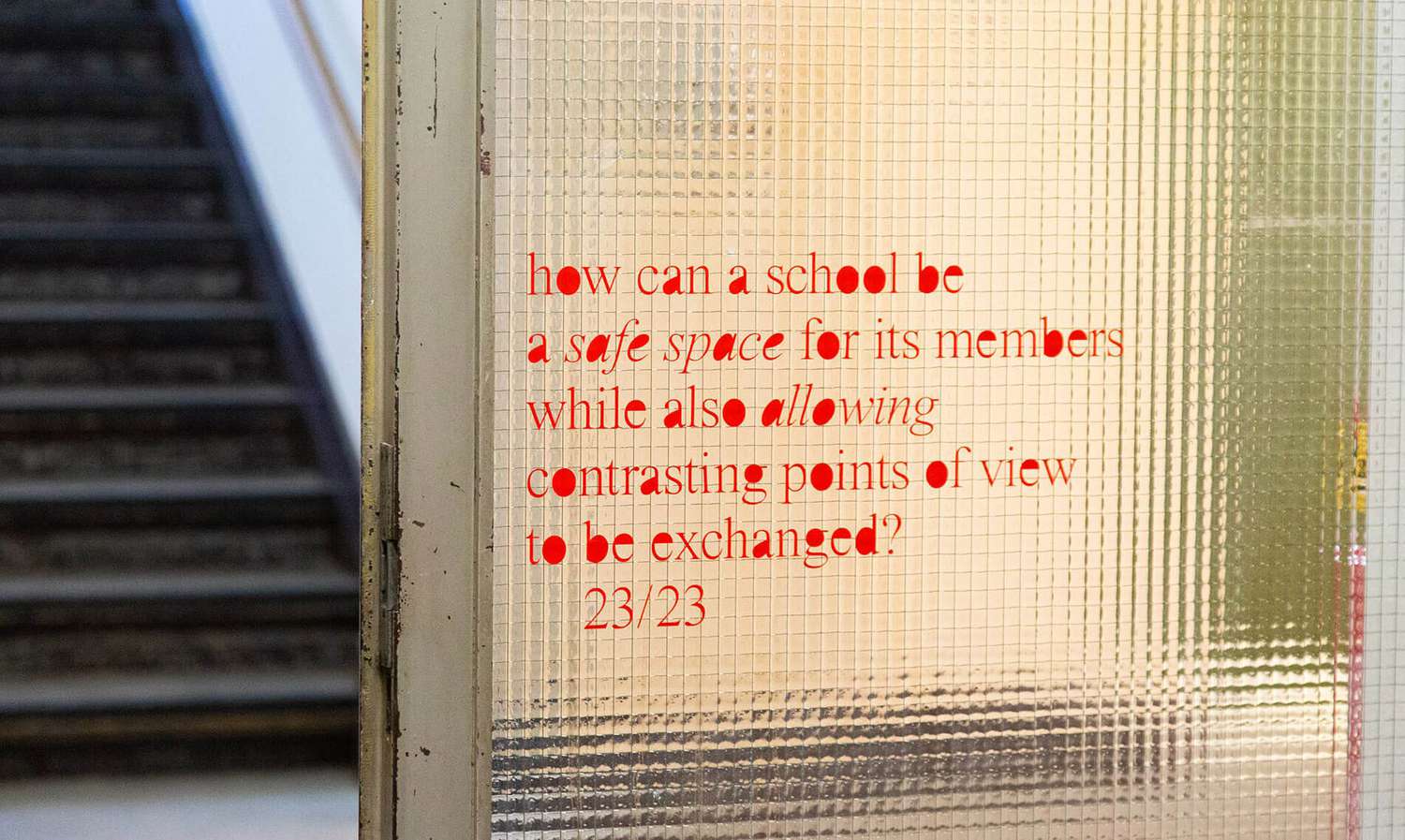

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Graduate Show 2023: Unfinished Business

Let`s work together

Let`s work together

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2023 an der HFBK Hamburg

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Symposium: Kontroverse documenta fifteen

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

Festival und Symposium: Non-Knowledge, Laughter and the Moving Image

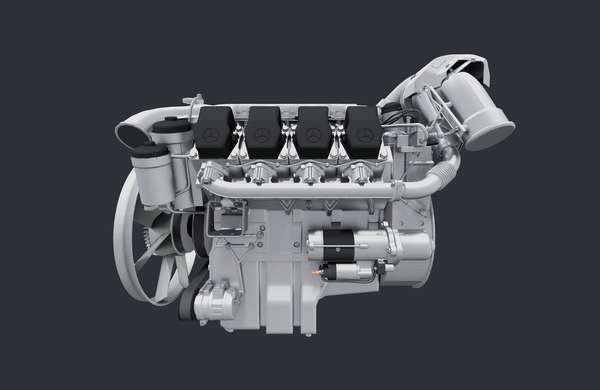

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

Einzelausstellung von Konstantin Grcic

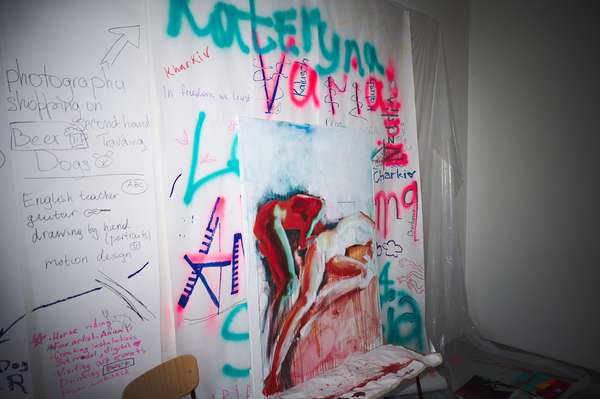

Kunst und Krieg

Kunst und Krieg

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

Graduate Show 2022: We’ve Only Just Begun

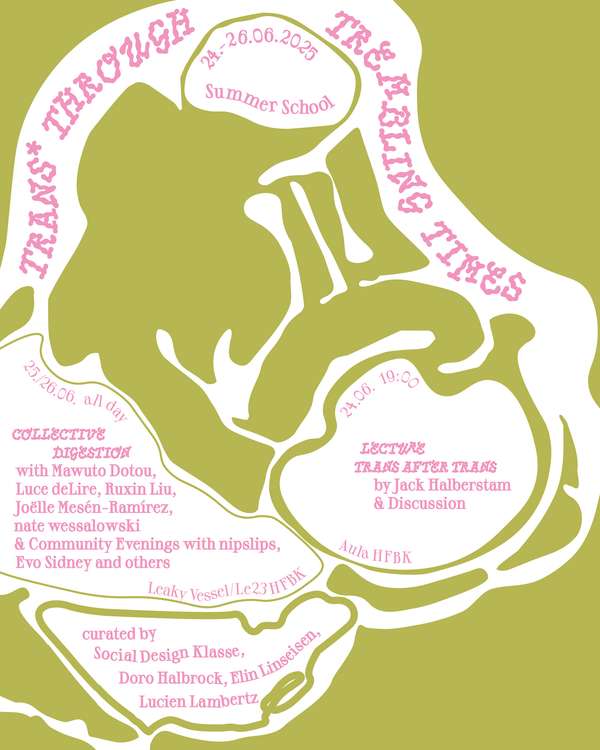

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Der Juni lockt mit Kunst und Theorie

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Finkenwerder Kunstpreis 2022

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Nachhaltigkeit im Kontext von Kunst und Kunsthochschule

Raum für die Kunst

Raum für die Kunst

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2022 an der HFBK Hamburg

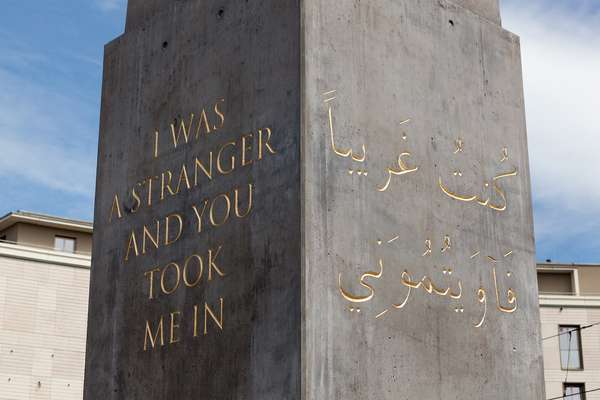

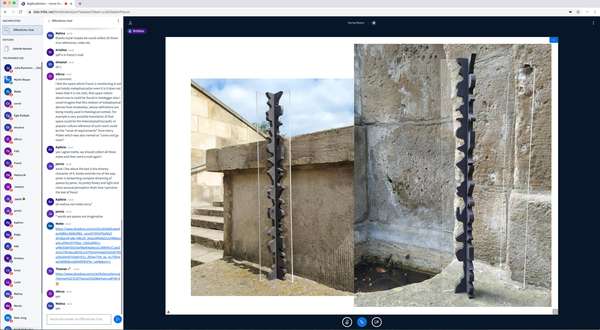

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

Conference: Counter-Monuments and Para-Monuments

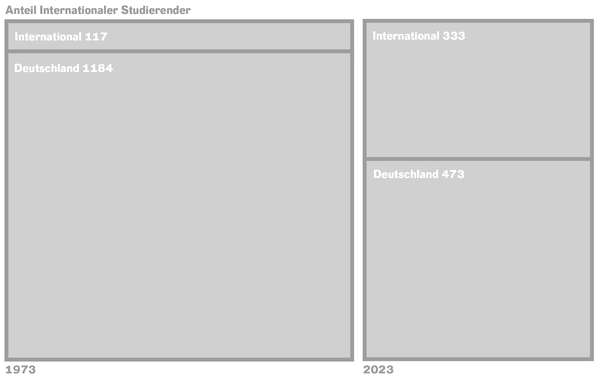

Diversity

Diversity

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

Live und in Farbe: die ASA Open Studios im Juni 2021

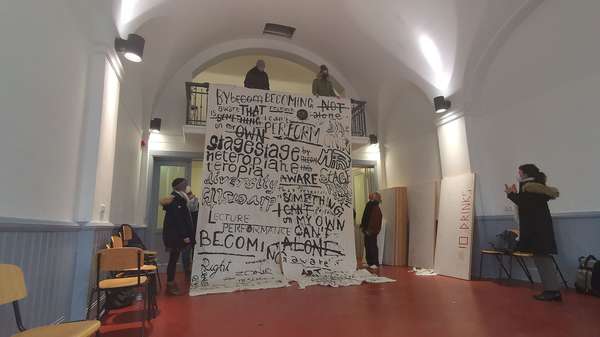

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

Vermitteln und Verlernen: Wartenau Versammlungen

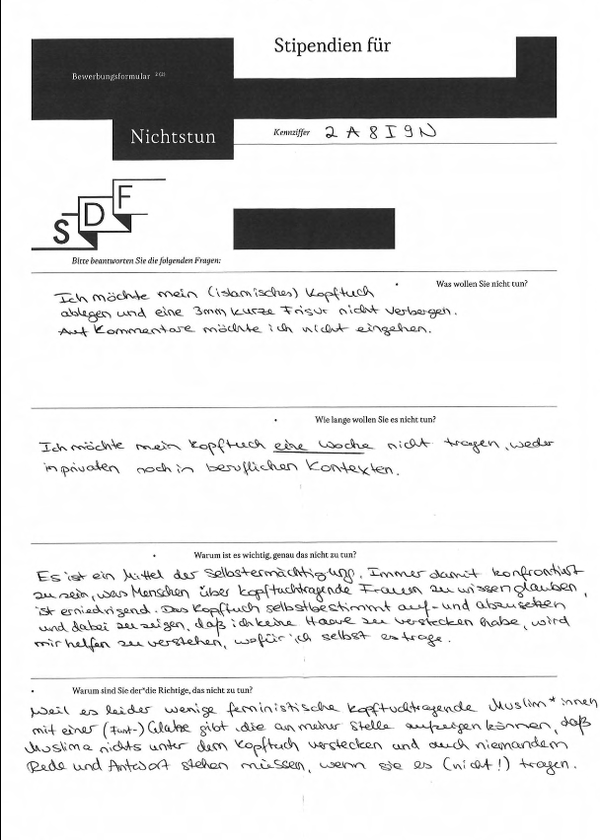

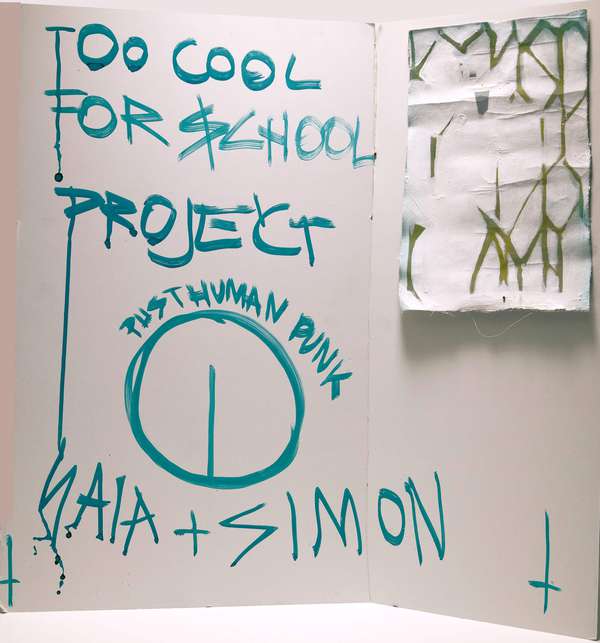

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Schule der Folgenlosigkeit

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Jahresausstellung 2021 der HFBK Hamburg

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

Semestereröffnung und Hiscox-Preisverleihung 2020

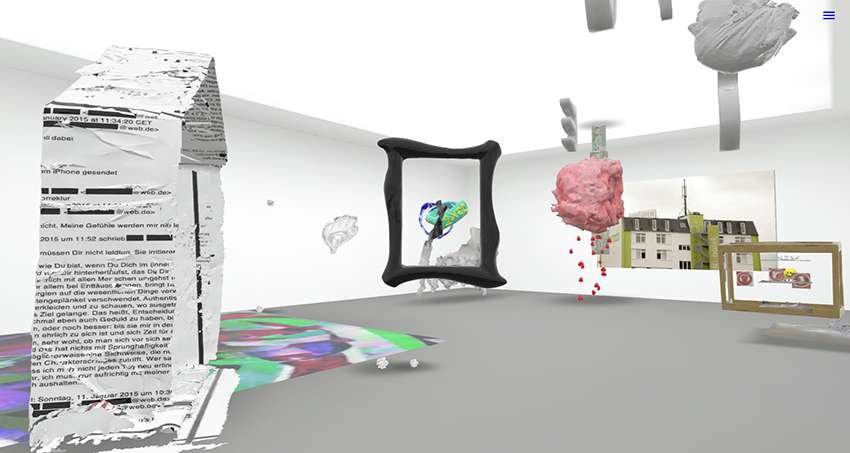

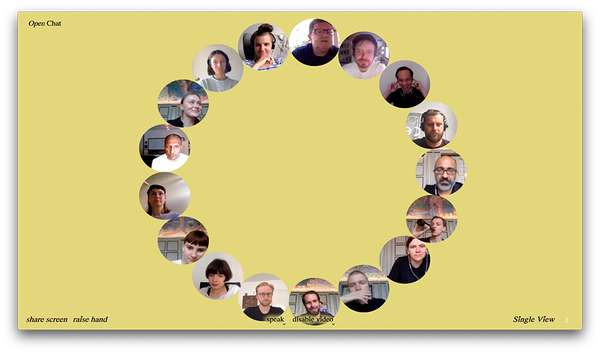

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Digitale Lehre an der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

Absolvent*innenstudie der HFBK

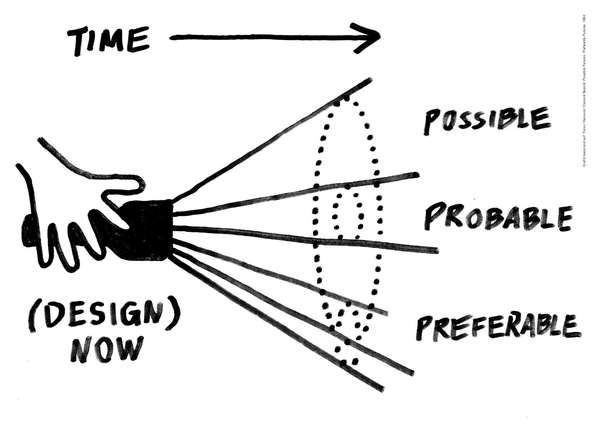

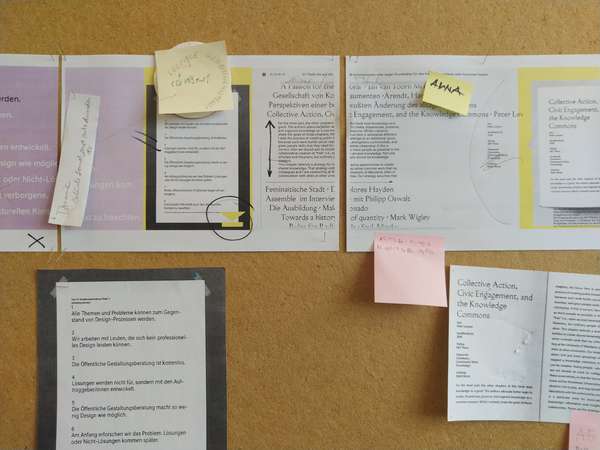

Wie politisch ist Social Design?

Wie politisch ist Social Design?